Zara, H&M Linked to Illegal Deforestation & Human Rights Abuses with Brazilian Cotton Supply Chain

8 Mins Read

Industrial cotton farming in Brazil that’s sold to Asian suppliers of Zara and H&M is destroying the Cerrado savanna and violating the rights of local communities, a new investigation has revealed.

Zara & H&M – two of the world’s largest fashion companies – source cotton from industrial farms in Brazil that are accused of illegal deforestation, land grabbing, violent conflicts and corruption. These practices are violating the human rights of local communities and tearing down the Cerrado, the world’s largest savanna, according to a new report by climate NGO Earthsight.

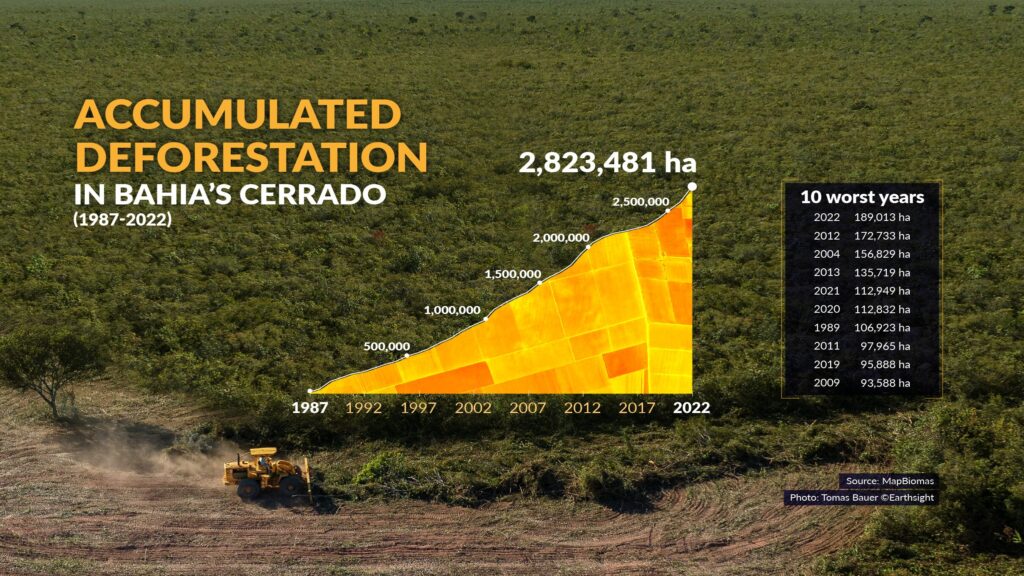

Lying south of the Amazon, the Cerrado is home to 5% of the world’s animals and plants, encompassing 161 species and millions of humans depending on its forests for their livelihoods. But half of the biome’s native vegetation has already been lost to industrial farming by agribusinesses turning their attention to the Cerrado to spare the Amazon. And just last year, deforestation rates in the region increased by 43% – almost all of which is illegal.

“While we all know what soy and beef have done to Brazil’s forests, cotton’s impact has gone largely unnoticed. Yet the crop has boomed in recent decades and become an environmental disaster,” said Earthsight director Sam Lawson. “If you have cotton clothes, towels or bed sheets from H&M or Zara, they may well be stained by the plundering of the Cerrado.”

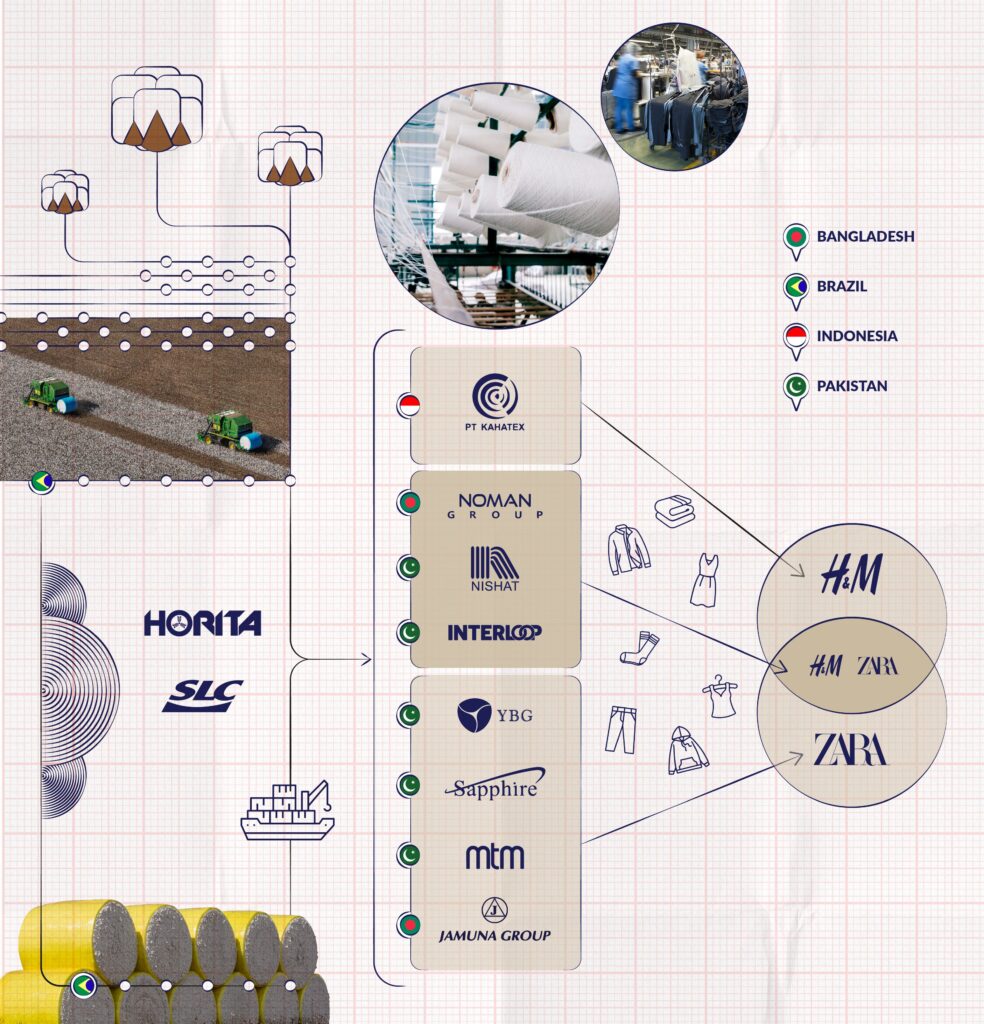

Video footage from the year-long investigation shows a community member being shot, lands being burned, and large swathes of green fields being cleared, tracing over 800,000 tonnes of cotton back to firms in Asia that make clothes for Zara and Inditex (the parent company of Zara, Pull&Bear, Massimo Dutti, Bershka and Stradivarius), which together have over 10,000 locations and made $41B in combined revenue in 2022.

SLC Agrícola and Grup Horita’s land-grabbing and violent history

Brazilian cotton has become much more prominent in the fashion industry over the last decade, with the country now the world’s second-largest exporter of the crop, and set to overtake the US by 2030. In the last decade, Brazil’s cotton exports have more than doubled, and almost all of this is grown in the Cerrado.

The investigation found that H&M and Zara’s suppliers source cotton grown in the Brazilian state of Bahia by two of its largest producers: SLC Agrícola (which is the top producer) and Grupo Horita (the sixth-largest). Both owned by some of Brazil’s wealthiest families, their cotton production in western Bahia is linked to a number of illegalities.

The region has been heavily impacted by industrial agriculture, with locals telling Earthsight it’s hard to find a single large-scale cotton or soy farm in all of western Bahia that isn’t the result of land grabbing. Agribusinesses extract nearly two billion litres of water daily from the area, but dump 600 million litres of pesticides on the Cerrado every year. The heavy use of pesticides gives cotton an “extremely high” climate footprint – clearing Cerrado vegetation for agriculture emits as much carbon as 50 million cars in a year.

Horita grows cotton, soy and other crops on a third of a mega estate called Estrondo in a Bahia municipality. It has been linked to violent land disputes that pit Estrondo against Indigenous communities called geraizeiros, who have inhabited the area since the 19th century and have their right to traditional lands protected by law. Bahai’s attorney general ruled in 2018 that Estrondo was one of the largest land-grabbed areas in Brazilian history, but these public lands belong to the state and should be environmentally protected and set aside for the local population.

Over half of the area illegally appropriated by Estrondo’s owners in the 1970s and 1980s has been deforested, and in the last 10 years, the traditional communities have faced intimidation and harassment by armed men working for the agribusinesses. In 2019, two community members were shot by Estrondo’s security guards.

One of Grupo Horita’s owners, Walter Horita, has been caught in a corruption scandal for the sale of court rulings related to land disputes in Bahia, with attempts to influence judicial and political stakeholders in the region, and reports of him transferring $1.2M to a court official.

Another land-grabbing case has afflicted the Capão do Modesto community, with large agribusinesses accused of misappropriating public lands to convert them into “legal reserves”, which landowners must set aside for environmental prevention. But instead of keeping part of their productive properties as legal reserves, some agribusinesses have acquired land elsewhere to do so. Bahia’s attorney general has referred to Capão do Modesto as “one of the most serious land grabbing cases” in the region, with the local community facing harassment, surveillance, intimidation and attacks carried out by gunmen.

Better Cotton certification masks illegal deforestation

Both Grupo Horita and SLC Agrícola also have a history of illegal deforestation. The former’s farms were found to have illegally felled over 25,000 hectares, while there were no permits found for 11,700 hectares of deforestation by the company between 2010 and 2018. In fact, it has been fined over 20 times for environmental violations, totalling $4.5M.

And despite adopting a zero-deforestation policy in 2021, SLC Agrícola was accused of clearing over 1,350 hectares of native vegetation at one of its farms in 2022. That’s before you consider the 40,000 hectares its farms lost over the last 12 years. The business has also been fined over $250,000 since 2008 for its violations.

Earthsight notes how H&M and Zara rely on the Better Cotton (BC) certification system. All the cotton investigated by the organisation was BC-certified, and the two fashion giants are the world’s biggest users of such cotton. Brazil, meanwhile, produces the largest amount of BC-licensed fibre (42% of the global total).

But this system is “fundamentally flawed”, with BC having repeatedly been accused of greenwashing, not allowing for full supply chain traceability, and failing to protect human rights. The certification has “excessively vague” requirements to comply with local laws and no mention of land ownership or disputes. A 2019 ban on ecosystem conversion doesn’t address illegal deforestation, while an upcoming traceability system is inadequate as it traces cotton back to countries, not farms.

H&M and Inditex don’t have the policies and tools in place to make up for BC’s shortcomings. The former’s human rights and sustainability policies fail to address community rights or deforestation, while the latter’s climate commitments don’t extend to its cotton suppliers. BC has now launched an investigation into the allegations.

In a statement, H&M said it took the findings “extremely seriously”. “Even despite the standard owners’ best efforts, violations can of course occur. Therefore, it is essential that the standards and certifications we select have credible grievance mechanisms and incident management processes in place that enable remedy,” it said.

“We have commercial relationships with all these companies. Inditex’s purchases from these organisations represents a fraction of their total production,” said Inditex. “Accordingly to suppliers’ information, these companies do not directly purchase cotton to any Brazilian producer. They purchase cotton with different origins throughout specialised traders depending on the raw material characteristics, certification and price.”

What governments and companies need to do

The report notes that government reforms are needed to transform the cotton and fashion industries, given their weak supply chain oversight and ineffective certification systems. The EU, for its part, is close to finalising its Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive – but this will be a watered-down version of the original proposal, thanks to Germany’s withdrawal of support for the law. This was driven by the FDP (part of the governing coalition in the country), which has received funding from businesses that would be affected by the law.

Last year, the EU’s Deforestation Regulation came into force to require the production of certain goods to be legal and free from deforestation, but it does not cover cotton or goods made from cotton. This is also the case with the UK’s illegal deforestation ban and the US’s Forest Act. In Brazil, the federal government is promoting the PPCerado plan to reduce deforestation in the savanna, but this also only targets illegal deforestation and fails to address land clearing authorised by the local government.

Successive Bahia governments have also adopted regulations that undermine the state’s constitutional provisions on environmental and community protection. Earthsight suggests that the approval of deforestation permits has skyrocketed, with over 750,000 hectares authorised between 2012 and 2021. “The federal government should put in place a plan to halt all large-scale deforestation in the Cerrado, not only the illegal kind,” the report states. “Bahia’s government should map all public lands to ensure they are preserved and that traditional communities fully enjoy their land rights.”

Earthsight says Better Cotton must require certified farms to seek the consent of Indigenous communities for any activities that affect them, while rules on deforestation need to ban certified cotton from growing on land that was deforested illegally before December 2019. Conflict of interest issues also need to be resolved by putting impartial parties in charge of certification and audits.

Better Cotton is also being asked to implement and enforce a meaningful traceability system, with H&M, Zara and other big retailers called upon to pressure the accreditation programme to do so. Until that happens, these businesses need to go beyond using certifications and ensure their goods are sourced ethically by introducing more rigorous policies and checks.

“These firms talk about good practice, social responsibility and certification schemes, they claim to invest in traceability and sustainability, but all this now looks about as fake as their high-street window arrangements,” said Lawson. “It has become very clear that crimes related to the commodities we consume have to be addressed through regulation, not consumer choices. That means lawmakers in consumer countries should put in place strong laws with tough enforcement. In the meantime, shoppers should think twice before buying their next piece of cotton clothing.”