WWF’s Peter McFeely On Planet-Based Diets: No Global Change Without Localized Food Systems

7 Mins Read

The World Wildlife Federation (WWF)’s Global Head of Communications, Food Practice, Peter McFeely, talks to Green Queen‘s Sonalie Figueiras about the organization’s new Planet-Based Diets Calculator tool, why local change is crucial for global food system transformation, the difference between sustainable diets and healthy diets and the problem of overconsumption.

What is the WWF Planet-Based Diets Calculator, exactly?

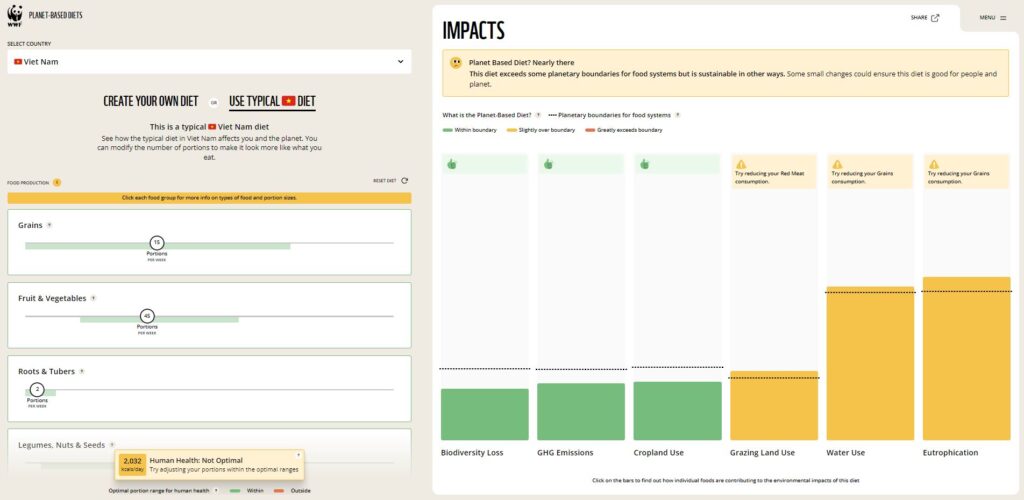

Peter McFeely: The WWF Planet-Based Diets Calculator is an interactive tool that allows users to assess the human health and environmental impacts (including land use, water use and GHG emissions) of their own weekly diet, and what would happen if everyone in their country ate like them. With data from nearly 150 countries that accounts for how foods are sourced and produced differently around the world, the calculator provides key insight into the national-level changes needed to benefit climate, nature and people.

The tool was first launched in 2020 and it was recently updated. Can you share about this and why it was created in the first place?

Peter McFeely: We built the Planet-Based Diets Calculator because many people don’t understand the impacts of what they eat on the planet, or feel they don’t have reliable information to make changes that will be good for both nature and their own health. A couple of years ago we launched the Planet-Based Diets platform, which outlines what would happen to nature and the climate if various different consumption patterns were adopted by everyone in specific countries – if there would be more GHG emissions, fewer trees, or we’d use more water. The new Calculator allows someone to see what would happen based on their own specific diet, so someone can see what exactly eating one less portion of meat or several more portions of fruit and veg per week means. We hope that this will help people consider adjusting their consumption patterns and eating more mindfully.

What’s your intended audience? Who did you create the tool for?

Peter McFeely: Everyone! At least those of who us who are lucky enough to be able to choose what we eat several times a day. By building a simple interactive format that updates as you change the diet, and focusing on the number of portions of different types of food each week (instead of calories or grams) we hope most people can see how small changes can have big impacts. While the interface is clean, there’s a lot of complex data behind the Calculator, so it could also be useful to anyone working in food science or policy, as they consider the impact of different actions.

What are some interesting variances you found in terms of optimal diets in different regions of the world?

Peter McFeely: Firstly, we have to note that in many industrialised countries, there is an overconsumption of calories and bringing food consumption to within healthy ranges will be good for the environment; but in other countries, improving public health requires the overall consumption of food to increase and this will mean national food-based environmental impacts go up. So we have to find a way to balance the needs of different countries to bring diets within planetary boundaries.

It is also interesting to see what different foods drive different environmental impacts in different countries. Take biodiversity loss – in Brazilian diets, for example, red meat is by far the biggest driver so people can only sustainably eat small amounts each week. However, red meat plays a smaller role in biodiversity loss attributed to Danish diets. Even if Danes eat within a healthy range, biodiversity loss would still be high, due to the large impacts of coffee and cocoa. There also needs to be a significant reduction in these items. Likewise, for water use, the biggest impact in the Netherlands is dairy consumption, but in the United States, it’s grains. So different actions are needed in different places.

Is there a difference between sustainable and healthy, or said differently, between human health and planetary health?

Peter McFeely: Yes – sustainable means it’s good for the planet, healthy that it’s good for people. But one doesn’t automatically equal the other. There are plenty of diets that could be within planetary boundaries (i.e. the environmental limits of what we can sustainably produce) but not provide optimal nutrition, either in terms of being within recommended calorie ranges for the average person or having an ideal balance of different types of food. Likewise, there are diets that deliver the right nutrition, but if everyone adopted them we’d exceed planetary boundaries. We’ll only have resilient food systems that can provide for everyone if they are both healthy and sustainable.

Can you tell us more about the science behind the tool? What kind of research/methodology went into it?

Peter McFeely: We teamed up with leading scientists to develop cutting-edge methods for assessing the environmental impacts of producing food in individual countries and the human health impacts of consuming this food and created a complex means of measuring how changes across different good groups would change the impacts. This is one of the most comprehensive assessments of the impacts of diets around the world and builds upon research previously published in Science and the British Medical Journal. More details on how we assessed existing consumption, defined human and environmental impacts and considered different dietary patterns is available here.

What do you think is the best thing governments could do to promote sustainable diets?

Peter McFeely: What the Calculator clearly shows us is that things aren’t the same everywhere in the world. There isn’t one global food system and we need localised plans to transform national and sub-national food systems so that they are healthy and sustainable. There is no one-size-fits-all solution. In some places governments may make healthier food cheaper, in others tax food that has high environmental impacts; it could be they subsidise farmers, increase regulation across supply chains, or run educational campaigns for the public. The most effective solution is going to depend on the local challenges.

What are some of the biggest misconceptions people have about sustainable diets?

Peter McFeely: Unfortunately, when it comes to healthy and sustainable diets, there are a lot of myths out there. What we eat is highly personal, and for every person who says something is bad, you’ll like find someone else who said it was good for them. A few of the things we hear persistently are that local food production is always more sustainable and that we should all stop eating meat.

In a lot of local contexts, these may be largely true, but there are a lot of countries that could never sustainably produce enough healthy and nutritious food locally, and importing certain foods may be a more environmentally-friendly practice. When it comes to meat, it’s clear that globally we need to reduce meat consumption – but there are some countries in which there are no nutritious alternatives readily available, and some people may even need to increase the amount of animal-sourced foods they eat. But if we choose to eat meat it should only be a part of our diet, not the centrepiece. For all of the emissions and water use associated with meat, our planet can sustain the production of some meat, and there is evidence that raising cattle on well-managed, natural grasslands can actually enhance soil quality and biodiversity. The key is only eating what these grasslands can sustain – which is much lower than the volume of meat and dairy currently being consumed globally.

My colleague Brent Loken, WWF’s Global Food Science Lead has written a great blog post busting common myths when it comes to healthy and sustainable diets and it’s worth reading.

What were some of the key learnings around diets and the impacts of climate change?

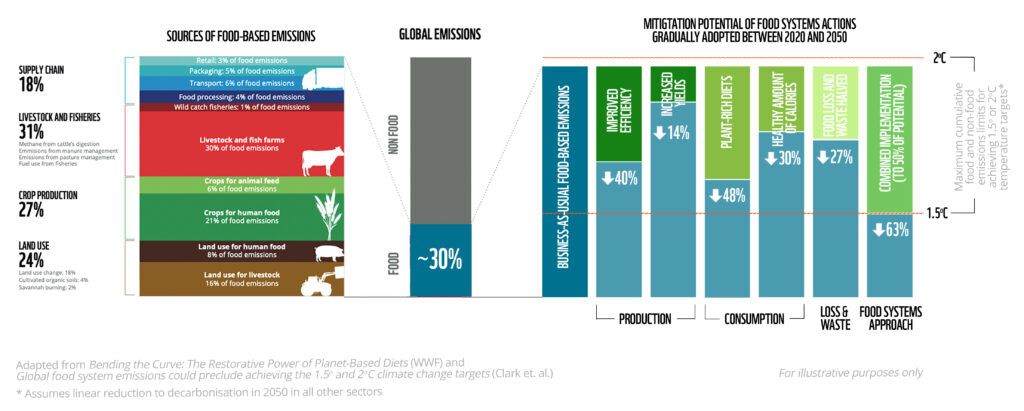

Peter McFeely: Food systems produce around a third of all greenhouse gas emissions – there’s no way to limit global warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius if we don’t urgently transform food systems. Even if all other sectors (like manufacturing and energy) decarbonised by 2050, business-as-usual food systems would use nearly the entire carbon budget of a 2oC world. To bring food-based emissions down to the 1.5oC budget, we have to implement a combination of actions across food production, consumption and loss and waste. But the single most impactful action is changing what we eat. If everyone ate a healthy amount of calories (i.e. we reduced overconsumption) we could reduce food-based emissions by as much as 30%, and adopting plant-rich diets could reduce them by as much as 48%. It’s clear that shifting to healthier and more sustainable diets will play a significant role in limiting the worst effects of climate change.