WWF: ‘Everyone Has a Role to Play in Tackling the Global Water Crisis’

7 Mins Read

The annual economic value of water and freshwater ecosystems is estimated to be $58T, the equivalent of about 60% of the world’s GDP, according to the World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF). Not only does the degradation of water bodies endanger their economic value, it threatens food security, human health and environmental sustainability.

As the horrific situation in Israel continues, the two million residents of Gaza are at risk of running out of water, with Israel cutting off water and electricity supply after attacks by the militant group Hamas. This means people are now forced to use dirty water from wells, exacerbating the risk of waterborne illnesses in a region that has long struggled with water contamination and freshwater shortage. As Philippe Lazzarini, commissioner-general of the UN Relief and Works Agency, puts it: “It has become a matter of life and death.”

The water crisis is impacting all parts of the world. In the EU, 30% of the population has been impacted by shortages in the last few years. The region has lost up to 90% of its floodplains in recent centuries, while 60% of its rivers, lakes and other surface water bodies are not in good condition. This is set to continue, with 90% of EU waterbeds expected to still be unhealthy by 2027.

And in the US, the mayor of New Orleans, Louisiane recently declared a state of emergency over high salt concentrations in the drought-hit Mississippi River, a year after Mississippi state capital Jackson saw its largest water treatment platform fail, leaving its 160,000 residents without safe drinking water.

These are just a handful of examples of how the water crisis is impacting the planet and its people – and if you listen to the WWF, it says that this calamity threatens food security, climate change and the global economy. Since 1970, the world has lost a third of its remaining wetlands, while freshwater wildlife populations have fallen by 83% on average.

These are “disastrous trends”, the WWF says, which have led to an undermining of global efforts to reverse nature loss and adapt to climate change’s effects, from droughts to floods. Today, half of the world’s population experiences water scarcity every month, while 55 million people face annual droughts.

The water crisis affects everyone and everything

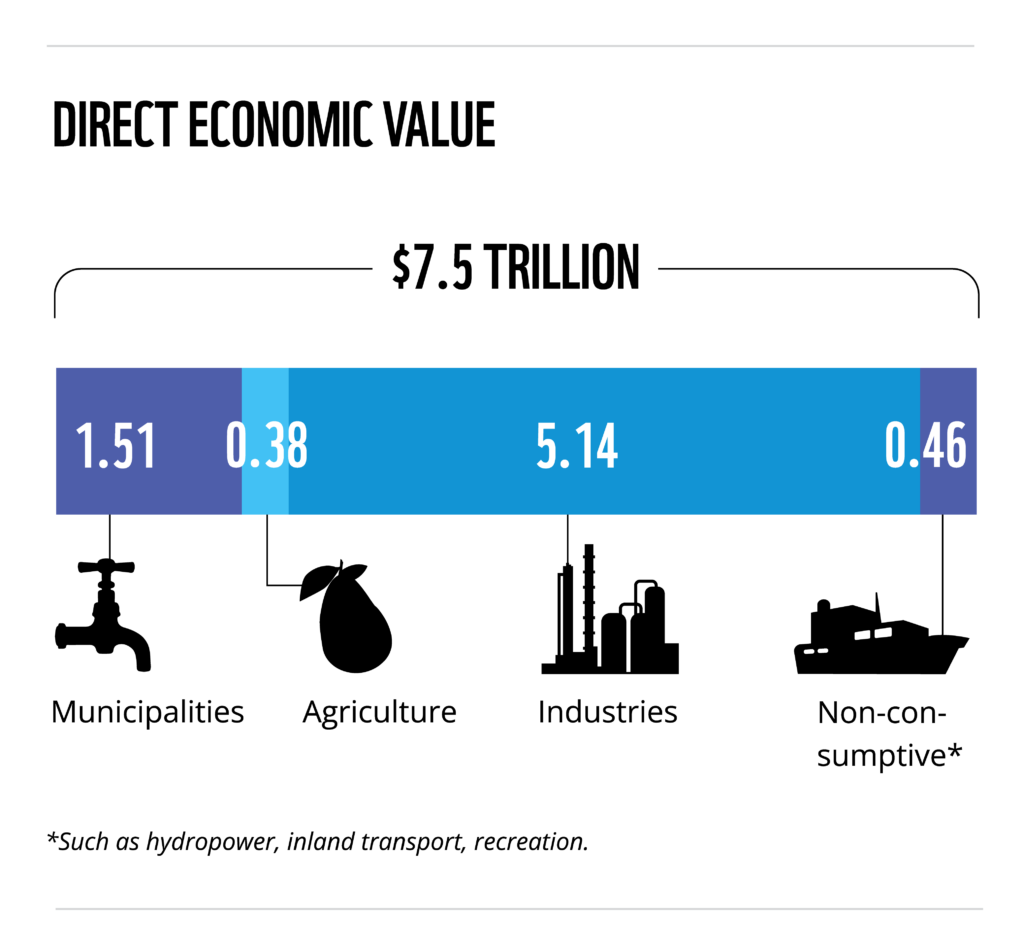

The new report by WWF, The High Cost of Cheap Water, finds that the direct economic benefits of freshwater ecosystems – like water consumption for households, irrigated agriculture and industries – amount to a minimum of $7.5T annually. Additionally, unseen benefits, such as purifying water, enhancing soil health, storing carbon and protecting communities from extreme floods and droughts are valued seven times higher at $50T per year.

The problem, as you may have already guessed, is that these ecosystems are in a “downward spiral”. The degradation of rivers, lakes, wetlands and aquifers is a threat to this economic value, as well as the crucial role they play in sustaining human and planetary health.

“Water and healthy freshwater ecosystems underpin our societies and economies, and are fundamental to human and planetary health,” WWF’s global freshwater lead Stuart Orr tells Green Queen. “The worsening water crisis – from increasing water scarcity to floods and pollution – is leading to increasing numbers of people facing water and food shortages, which undermine health and wellbeing and livelihoods.

“But the water crisis goes beyond that. Water risks to businesses and investors are increasing, with more operations being impacted by floods, droughts and poor water quality, while more assets are being left stranded and drowned.”

She reiterates WWF’s point that healthy water bodies are crucial for people and the planet. “Peatlands, for example, are a significant carbon sink, while healthy freshwater ecosystems help to defend our communities and cities from extreme floods and build resilience to droughts,” explains Orr. “Freshwater ecosystems are our life-support systems. Protecting and restoring them is essential to our future and to hopes for sustainable development.”

The water crisis and food insecurity go hand-in-hand

One of the primary threats to rivers and floodplains (and, incidentally, climate change too!) is agriculture – more specifically, unsustainable farming practices. The World Bank says this sector accounts for 70% of all freshwater used by humanity. Over-extraction for crop irrigation reduces water availability for other uses and contributes to shortages.

Meanwhile, lands used for intensive agriculture occupy territories of former floodplains – this has led to lower purification levels as well as flood and risk capacities of rivers. Moreover, the excessive use of fertilisers creates diffuse pollution, which affects both surface and groundwater.

The WWF says the destruction of these ecosystems, combined with poor water management, has left billions worldwide with a lack of access to clean water and sanitation. Meanwhile, economic risks are growing – by 2050 around 46% of the global GDP could come from areas facing high water risks, up from 10% today.

“Threats to river systems are threats to food security,” says Irene Lucius, regional conservation director at WWF Central and Eastern Europe. “Only by protecting and restoring rivers and their active and former floodplains, keeping water in the landscape with natural water retention measures can we hope to maintain the productivity of agricultural systems into the future.”

How can we do so? “We must support nature-positive food production; maintain free-flowing rivers; apply sustainable land use practices better adapting to natural conditions and facilitating natural water retention; and adopt diets that reduce demand for products that strain freshwater resources,” explains Lucius.

Orr adds: “Degraded rivers and wetlands can be restored. There are lots of examples across the world, including the remarkable growth in the dam removal movement in recent years. Removing obsolete dams and other barriers from rivers is a swift and proven way to boost biodiversity and resilience and restore rivers. Peatlands can be re-wetted, floodplains can be reconnected to their rivers.”

Governments need to update their thinking

The report, published on World Food Day (October 16), points to how our food system damages our water system. “Our current food production practices are not only harming the freshwater ecosystems, but are also identified as the primary contributors to biodiversity loss and climate change. They are causing land erosion and reducing the capacity of landscapes to deal with water scarcity and droughts,” explains Lucius. “Yet the food industry can drive a positive change by embracing leading sustainability practices.”

The WWF is calling on governments, businesses and financial institutions to intervene and step up their investment in sustainable water infrastructure. “Governments across the world have invested huge amounts to try and ensure water for all,” notes Orr.

“But what they – and decision-makers from business and finance – invariably fail to do is value, prioritise and invest in freshwater ecosystems, which store and supply water as well as provide a diversity of other values – many of which have no [economic] value, but are essential for cultures and communities. Decision-makers need to urgently wake up to the fundamental value of water and healthy freshwater ecosystems to societies and economies.”

In addition, the WWF cautions against “outdated thinking” on water solutions. “Decision-makers have always relied on built, concrete infrastructure to provide with water for drinking, irrigation and energy, and to reduce the impact of floods. But it is clear that we can no longer rely solely on built, concrete infrastructure,” explains Orr.

“The worsening water crisis, degradation of nature and disruptions to the water cycle caused by climate change mean that decision-makers need a new approach – one that relies on the best overall mix of built infrastructure and nature-based Solutions, including investing in protecting and restoring rivers, lakes, wetlands and aquifers, to store more water in nature for dry time, mitigate floods and pave the way for a net-zero, nature-positive and resilient future.”

The need for collaboration

One solution is the Freshwater Challenge, a nations-led initiative aiming to restore 300,000km of degraded rivers and 350 million hectares of degraded wetlands globally by 2030, as well as protect intact freshwater ecosystems. Launched at the UN Water Conference in March, it will help countries develop their national targets and secure the funding to achieve them – the challenge has been selected as an official Water Outcome at COP28.

“It is a challenge that all countries should join,” states Orr, “as restoring so many degraded rivers and wetlands will boost water and food security, and global efforts to tackle nature and climate crises and achieve the SDGs.”

He adds: “We need to remember that water doesn’t come from a tap – it comes from nature. Water for all depends on healthy freshwater ecosystems, which are also the foundation of food security, biodiversity hotspots and the best buffer and insurance against intensifying climate impacts. Reversing the loss of freshwater ecosystems will pave the way to a more resilient, nature-positive and sustainable future for all.”

Orr concludes by saying that everyone has a role to play in tackling the water crisis: “Decision-makers in government, business and finance will have the most impact, but citizens must play their part – by educating others on the scale and urgency of the water crisis, embracing mindful consumption, supporting [the] conservation of freshwater ecosystems, championing water stewardship at work, and, where possible, advocating for change.