World Bank Bats for Alternative Proteins, Calls for Shift Away from Meat and Dairy Subsidies

8 Mins Read

The World Bank has asked countries to redirect their subsidies away from livestock farming and towards low-emission products, encouraging greater adoption of alternative proteins for a more secure planetary future.

In a landmark report highlighting the agrifood system’s impact on climate change and potential for mitigation, the World Bank has made a major statement about the financial prowess and giant ecological footprint of the animal agriculture industry.

The global financial lender has suggested a repurposing of subsidies from red meat and dairy towards lower-emission foods like fruits, vegetables and poultry, adding that alternative proteins like plant-based, cultivated and fermentation-derived options represent a low-cost, highly effective solution in mitigating global heating.

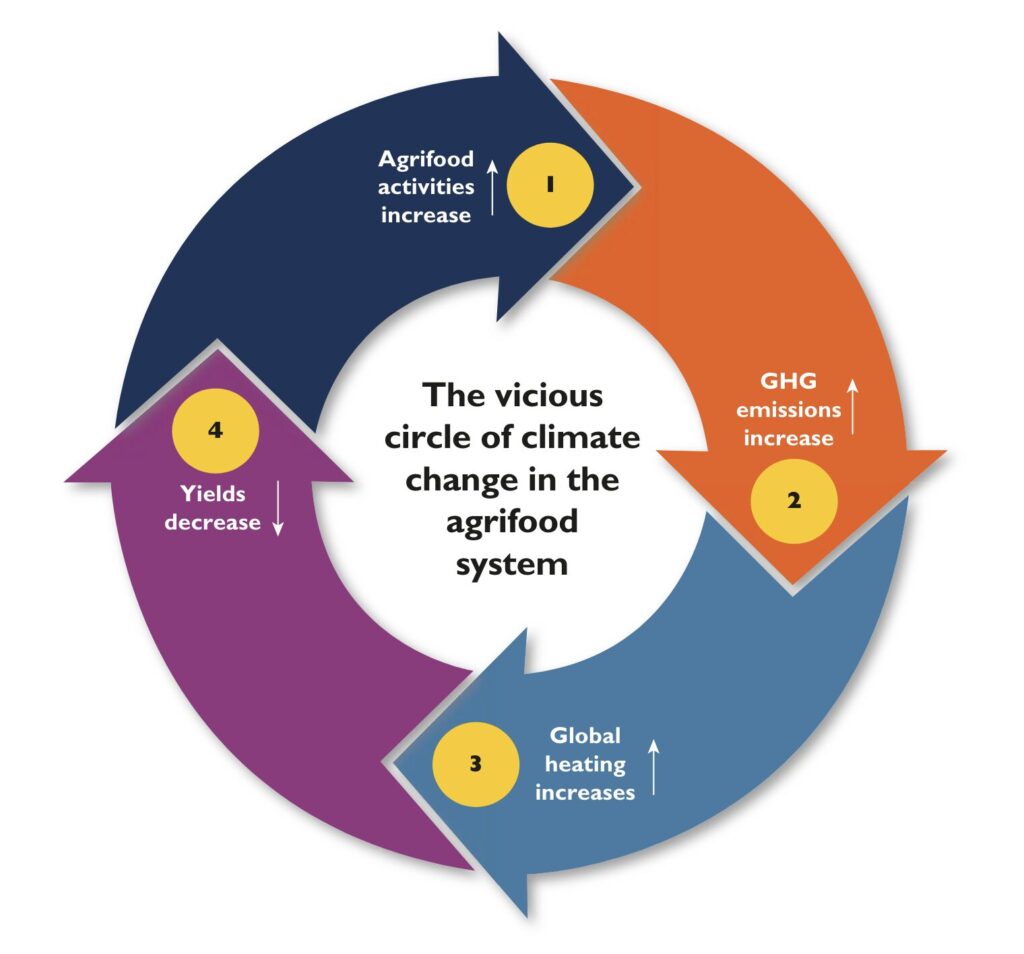

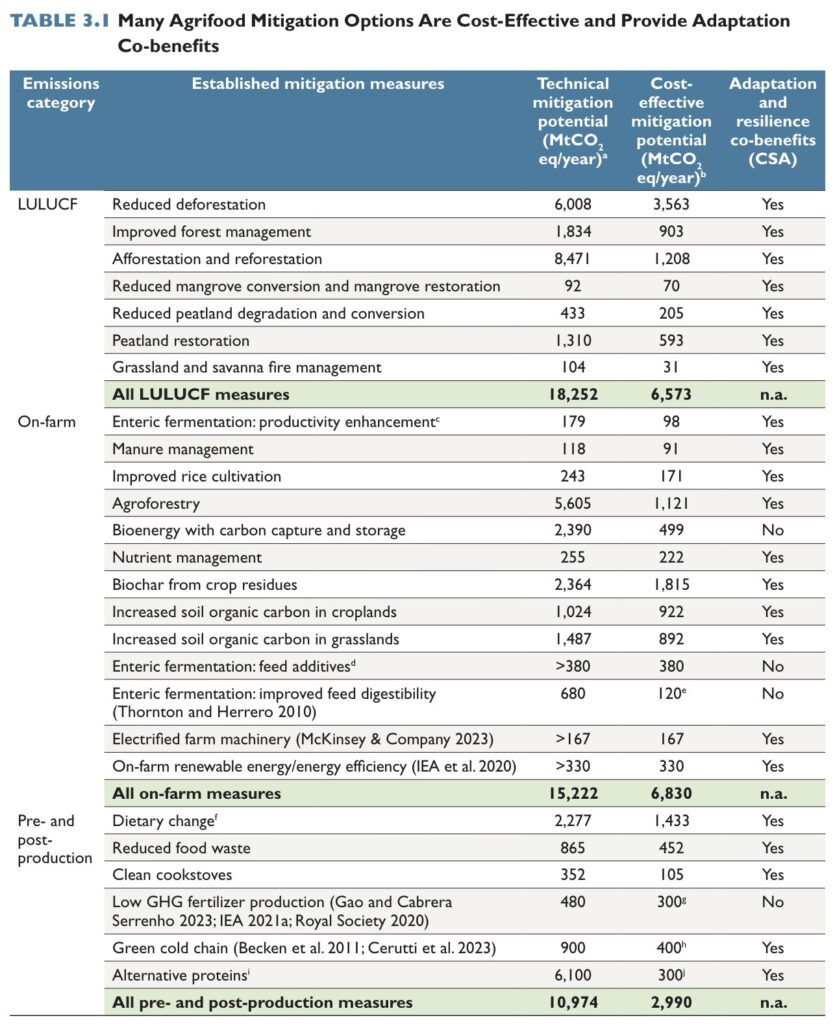

At current rates, we’re on track to breach temperature rises of 3.2°C since pre-industrial levels, which will have catastrophic effects on the planet. But the agrifood sector is a largely untapped source of affordable climate action, which can have an outside impact on the crisis, presenting the opportunity to cut a third of all emissions (about 16 gigatonnes a year) through readily available tools.

The Recipe for a Livable Planet report, which is the World Bank’s first comprehensive global strategic framework to mitigate the food system’s contribution to climate change and protect food security, says such actions will have three key benefits. They will make our food supply more secure amid a population that will count two billion more by 2050, they will help our food system withstand the ecological crisis better, and they will ensure vulnerable people are not harmed by the transition away from meat and dairy.

“We are faced with a startling and largely misunderstood reality: the system that feeds us is also feeding the planet’s climate crisis,” said Axel van Trotsenburg, senior managing director for development policy and partnerships at the World Bank. “The narrative is clear: to protect our planet, we need to transform the way we produce and consume food.”

Why tackling agrifood emissions is crucial

The World Bank notes how agricultural emissions are much larger than many think, accounting for 14% more emissions than heat and electricity. But agrifood emissions must reach net zero by 2050 if we’re to have a chance of meeting the 1.5°C goal outlined in the Paris Agreement, given they’re so high they could themselves make the world miss this target.

But too little money is being invested in reducing this impact. A separate report last year showed that only 4.3% of all climate financing goes to the agrifood system. The World Bank states that funding to reduce or remove agrifood emissions is “anaemic” at 2.4% of total mitigation finance. This needs to change among countries across the economic spectrum.

Three-quarters of these emissions come from developing nations, including two-thirds from middle-income countries, but mitigation action needs to happen in high-income states as well. Moreover, it’s important to take a food systems approach, including emissions from relevant value chains, land use change and those from the farm, since over half of agrifood emissions come from these sources.

Such action must be taken carefully to avoid job losses and food supply disruptions. Inaction, however, presents even greater risks to these factors, with the World Bank outlining that it would make our planet unliveable. If done correctly, mitigation action can bring about increased food security and resilience, better nutrition, improved access to finance for farmers, and biodiversity conservation, while securing jobs, good health and livelihoods for vulnerable groups and smallholder farmers.

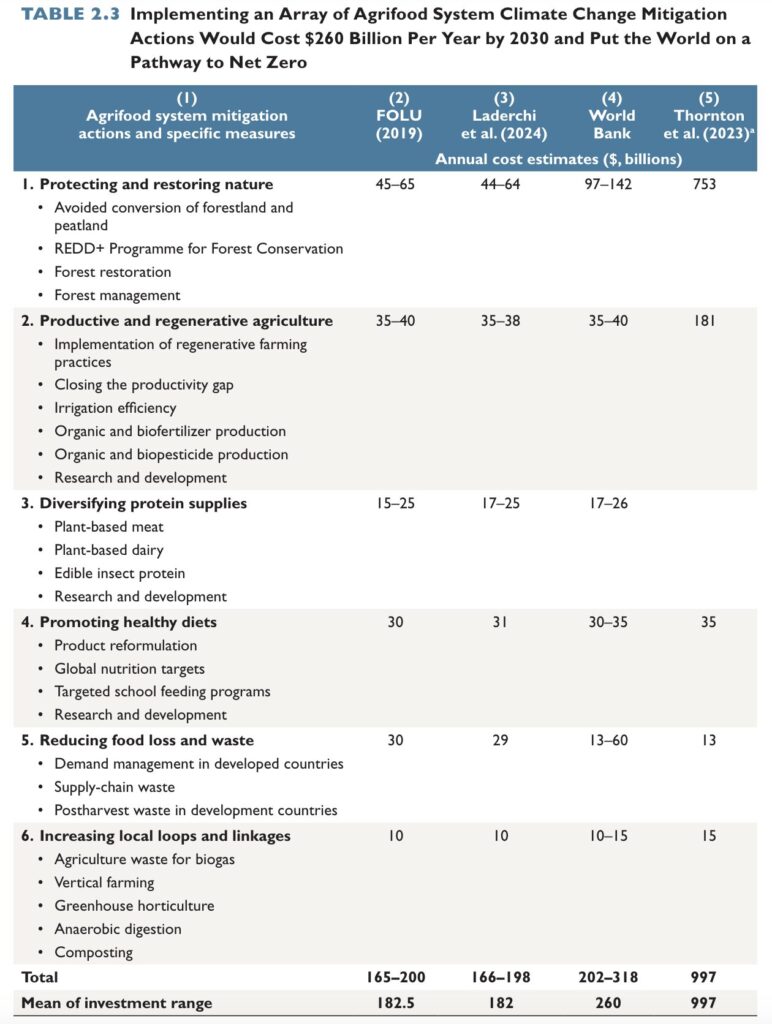

Investing in agrifood emissions reduction represents much larger payoffs than the costs. Countries need to inject 18 times more capital into this sector than they’re doing now, reaching $260B per year, to half emissions by 2030 and get on track for net zero by 2050. But the health, economic and environmental benefits could be as much as $4.3T by the end of the decade, which is a 16-to-1 return on investment.

One way to do this is to shift money away from “wasteful and harmful” subsidies, with the required investment for emissions cuts less than half the amount the world spends on agricultural subsidies. Still, the World Bank says substantial additional resources are needed to cover the rest of these costs.

The agrifood opportunity for countries

Low-income countries, which make up just 11% of the agrifood system’s emissions, should focus on “green and competitive growth” and avoid building the high-emissions infrastructure that richer countries need to now replace. Over half of the emissions here come from land use change, so preserving and restoring forests are cost-effective ways to cut emissions.

The World Bank encourages carbon credits and emissions trading to preserve forests as carbon sinks, though these tools come with major asterisks. But there are also benefits to be gained from climate-smart agricultural techniques and agroforestry practices.

Middle-income nations are responsible for the majority (68%) of the food system’s emissions, with 15 such nations accounting for two-thirds of the world’s cost-effective mitigation potential. A third of these reduction opportunities are linked to land use change, while fertiliser production, food loss and waste, household consumption, and methane from livestock are all areas to make cuts in as well.

High-income countries play a central role here. Making up 21% of all agrifood emissions, they have the highest energy demands for food production and must do more to promote renewable energy. They should also give more financial and technical support to low- and middle-income nations to adopt low-emission farming practices.

Richer countries should decrease their own consumer demand for emissions-intensive animal foods, according to the World Bank, which notes that these states can influence consumption by ensuring the climate and health costs of food are fully included in the prices. Moreover, repurposing subsidies from red meat and dairy towards low-emission products, and promoting sustainable food options, would be highly impactful as well.

World Bank champions alternative proteins

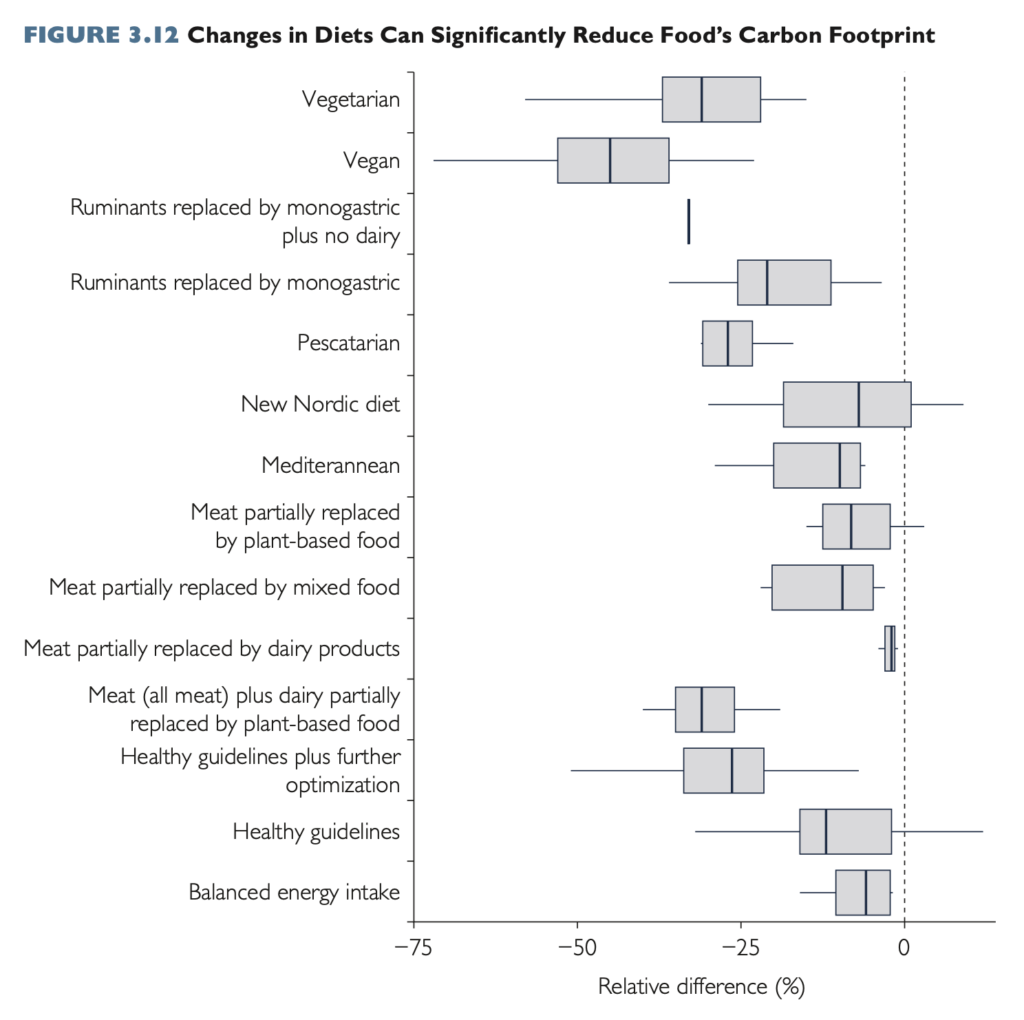

The World Bank’s report highlighted that rich countries have the highest demand consumption of climate-harming animal foods, which globally account for 60% of all agrifood emissions. UN bodies like the FAO have underlined solutions for less polluting animal agriculture, but the World Bank says shifting diets away from meat and towards plant-forward patterns is twice as effective as other mitigation methods (such as reducing enteric fermentation).

Meanwhile, full-cost pricing of animal foods – in other words, carbon taxes – would make low-emissions options more competitive. The report outlines studies that have shown meat prices need to increase by 20-60% to reflect the true costs on human and planetary health. This is why redirecting subsidies could lead to significant changes in consumption patterns – livestock farming receives 1,200 and 800 times more funding than alternative proteins in the EU and the US, respectively.

The World Bank spotlights plant-based meat, cultivated foods and other protein sources as innovative technologies that need more can greatly contribute to emissions reduction, but need much heavier R&D spending. Diversifying protein supplies through R&D, plant-based meat and dairy, and insect protein are some of the cheapest ways to lessen the climate footprint of the food system. This cost is earmarked to be up to $26B a year, much lower than the investment in protecting and restoring nature (up to $142B), regenerative agriculture ($40B), promoting healthier diets ($35M), and reducing food loss and waste ($60M).

Dietary change can result in a 70-80% decrease in food-related emissions and a 50% drop in land and water use. The World Bank suggests vegan diets are by far the most effective here, noting how one study found that while vegetarian eating patterns have a median emissions reduction potential of 35%, plant-based diets could cut emissions by nearly half (49%).

At another point in the report, it points out that plant-based and cultivated proteins have a 30-90% lower GHG intensity than animal-derived foods and could represent a reduction potential of at least 300 megatonnes of CO2e in the near term – and this is based on conservative estimates. “Technologies like cellular fermentation and plant-based protein can provide low-emission alternatives to meat. These methods can benefit animal welfare while reducing land, water, and nutrient consumption for livestock,” the World Bank says.

“Cultured meat could transform protein consumption practices, but its impacts on emissions are still relatively unknown,” it added, noting that the industry is facing many technical, ethical and political challenges. “These innovative products are still in their early stages and their development is contingent on continued investments, technological growth, regulatory endorsements, and consumer approval.”

World Bank needs to clean its own house too

The World Bank calls on governments, businesses, consumers and farmers to work together to repurpose wasteful subsidies, encourage low-emission agriculture, capitalise on emerging tech, and ensure a just transition by including vulnerable populations on the frontlines of the climate crisis. More sustainable food options can be advocated through measures like food labelling (including carbon, nutrition and sourcing data), choice architecture, education campaigns, and research in innovation in alternative proteins by governments.

“The food system must be fixed because it is making the planet ill and is a big slice of the climate change pie,” the authors say. “There is action that can be taken now to make agrifood a bigger contributor to overcoming climate change and healing the planet. These actions are readily available and affordable.”

Outgoing UN special rapporteur David Boyd summed up the frustration of human rights and climate activists in an interview yesterday. “I can’t get people to bat an eyelash. It’s like there’s something wrong with our brains that we can’t understand just how grave this situation is,” he said. “I think the right to a healthy environment is actually the foundation that we require to enjoy all other human rights. If we don’t have a living, healthy planet Earth, then all the other rights are just words on paper.”

The World Bank highlights the importance of making private investment in agrifood mitigation less risky, but its own private sector arm, the International Finance Corporation (IFC), has provided at least $1.6B to industrial livestock farming projects since 2017. This creates a mismatch between the lender’s climate and animal welfare pledges, and its investment actions, and the organisation is facing calls to phase out its financial support of animal agriculture.

The institution has said that climate change and animal welfare are central to the IFC’s agricultural investments, stating that large-scale projects can be used to develop more efficient, eco-friendly practices. But with its latest report, the World Bank needs to put its money where its mouth is – quite literally.