4 Mins Read

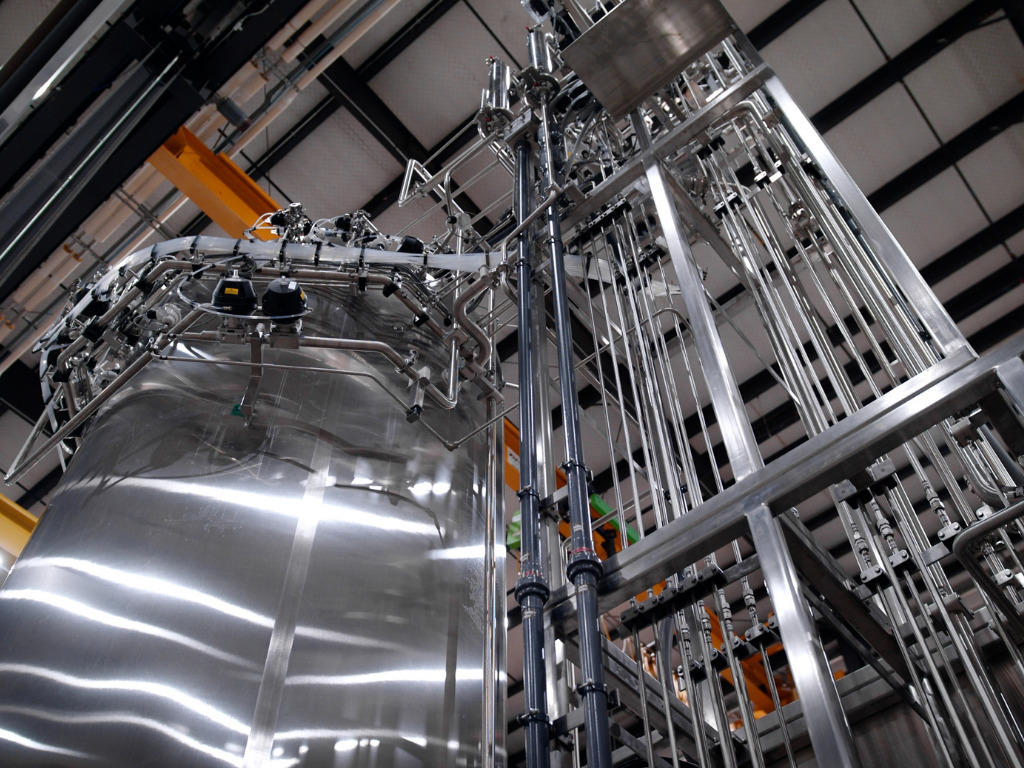

New research takes a look at the terminology surrounding cultivated protein — meat and seafood grown from animal cell samples in bioreactors.

It’s been called a lot of things — from “clean” meat to lab-grown, cell-based, and cultured meat. Its critics have labeled it Frankemeat. The industry has settled on “cultivated meat”. But what do consumers prefer? A new study took a look.

The research, published in the journal Nature Portfolio looked at U.S. consumers and their terminology preferences.

The findings

“We surveyed U.S. consumers to compare nine different labels for cultivated meat and seafood products in terms of appeal, purchase intent, perceived safety, perceived allergenicity, and clarity,” Chris Bryant of the University of Bath, said of the research. “We tested terms that were suggested by stakeholders in recent USDA and FDA calls for comments, as well as some additional terms.”

“Some had proposed that these products be labelled ‘artificial’ meat or seafood, but we found that this terminology was not a good representation of the nature of the products, and led to many people mistakenly thinking they would be safe for allergy sufferers. On the other hand, we also tested a completely new term, ‘Novari’, but we found that this had very low levels of consumer understanding,” Bryant said.

The terms earning the most favor were “cell-cultured” and “cell-cultivated.” “Artificial” and “lab-grown” were least favorable.

What the industry says

Ryan Huling, who leads communications and programs for the Good Food Institute’s Asia-Pacific region, says the researchers reiterate several important points that GFI has also made. GFI is the leading industry think tank. According to Huling, he’s not surprised that the nomenclature that invokes science and technology tends to have lower measures of appeal and purchase intent. “Put simply, consumers want to eat food, not tech,” he told Green Queen.

“It is also worth noting that this research was conducted in the U.S., where cultivated meat is not yet approved for commercial sale,” Huling said. U.S.-based Good Meat is the only company selling cultivated meat to consumers, currently; its cultivated chicken is available in Singapore. But the FDA recently GRAS status to U.S.-based Upside Foods, which is the first step in its path toward U.S. regulatory approval, bringing the country one step closer to the widespread availability of cultivated meat.

“GFI conducted a consumer study in 2019 with Mattson which helped determine our initial decision to use ‘cultivated’ terminology, while a more recent 2021 GFI survey of the cultivated meat industry demonstrated that ‘“’cultivated’”’ is also increasingly the preferred industry term,” Huling said.

He says adding “cell” before “cultivated” is redundant because even conventional animal meat is composed of cells.

“Describing animal products as ‘cultivated’ has been broadly shown to be most effective at fostering positive responses from consumers, while also being both scientifically accurate and a clear differentiator from conventional animal products,” Huling said. “That’s why more than 30 industry stakeholders — including nearly every cultivated food startup in Asia Pacific, as well as multinational companies Cargill and Thai Union and regional coalition groups from China, Australia, Japan, and Korea—have unified behind the term.”

Huling says that from a narrative standpoint, “cultivated” also facilitates increased consumer awareness by “drawing clear parallels with the familiar process of plant cultivation.”

“Just as growing plants in a greenhouse involves snipping off a small cutting from a plant and allowing it to grow in a nutrient-rich environment before harvest, we can now make meat by putting a small sample of animal cells into a nutrient-rich environment — known as a cultivator — and then harvesting them. This is a comparison that consumers around the world can easily wrap their heads around,” he said.

Robert E. Jones, President, Cellular Agriculture Europe, tells Green Queen the industry will need to make its case on nomenclature to regulators about labeling. He applauds the research.

“It is critical that we test both consumer acceptance and consumer clarity to simulate a real point of sale experience, yet most research to date has focused only on the former,” Jones said.

Jones says the new findings “make it clear” that the industry “must have the type of animal protein on the label to provide critical allergen information to consumers and that a modifier like cell-cultivated or cultivated will be important for clarity between our foods and conventionally produced foods.”

Similar research is coming to Europe as well, says Jones, giving regulators data to inform accurate and safe labels for the future of meat, seafood, and dairy. “The goal by all involved should be to keep agri-food politics from seeping into the process and to trust consumers to make the choices that are best for them.”