Study Links Ultra-Processed Foods to 32 Harmful Health Effects – But Critics Say There’s More Than Meets the Eye

7 Mins Read

A new health review has found that ultra-processed foods are directly associated with increased risks of cancer, heart disease and early death. However, experts question the use of this categorisation for nutrition, noting that these effects aren’t linked to all such foods.

The spotlight on ultra-processed foods (UPFs) has enlarged in the last year, and it will continue to do so after the world’s largest review of health studies directly linked UPFs to 32 harmful health conditions, including cancer, heart disease, type 2 diabetes, poor mental health, and early death.

Involving experts from leading institutions like the John Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health in the US and the University of Sydney, the umbrella review covered studies involving nearly, 10 million people around the world, and argued for the need to reduce UPF consumption.

“These findings provide a rationale to develop and evaluate the effectiveness of using population-based and public-health measures to target and reduce dietary exposure to ultra-processed foods for improved human health,” the authors wrote in the BMJ journal.

However, the study also noted that not all UPFs are bad, a sentiment shared by other experts and researchers not involved in the review. Some challenge the use of the Nova classification, which defines what a UPF is, as a measure of nutrition instead of what it was really designed for: how food is processed.

What health issues are ultra-processed foods linked to?

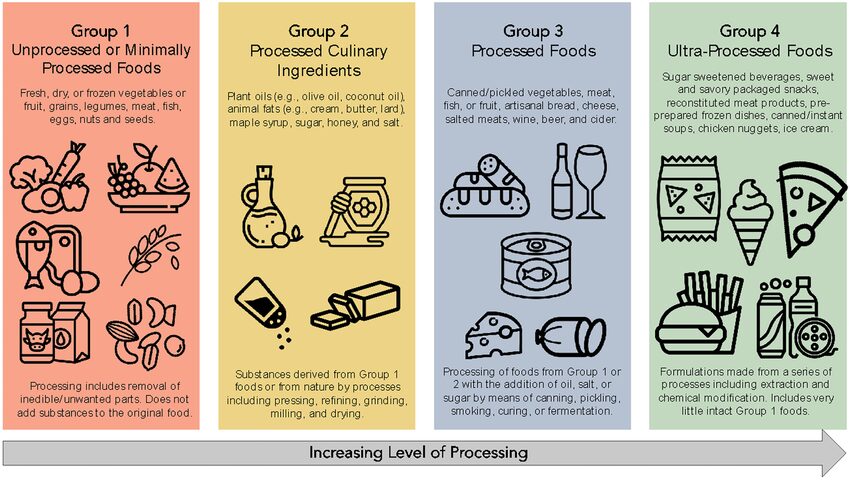

The Nova classification was created in 2009 by Brazilian researchers led by Dr Carlos Monteiro, who classified foods into four subgroups based on the level of processing. The first group comprises unprocessed or minimally processed foods (including whole foods), the second contains ‘processed culinary ingredients (think nut and seed oils, or salt), while the third category is made up of processed foods that can enhance shelf life and prevent bacteria (think fresh bread, cheese, and salted nuts).

The final group concerns UPFs, which the Nova classification defines as those produced via industrial formulations and techniques like extrusion or pre-frying, combined with cosmetic additives and substances of little culinary use, like high-fructose corn syrup, hydrogenated oils or modified starch. This involves products like ice creams, sugary cereals, fizzy drinks, and even ready-to-eat meals.

In the US, 73% of the food supply is made up of UPFs, contributing to 60% of the country’s calorie consumption. Similarly, they consist of 57% of an average person’s diet in the UK, with higher intake among children and people with lower incomes.

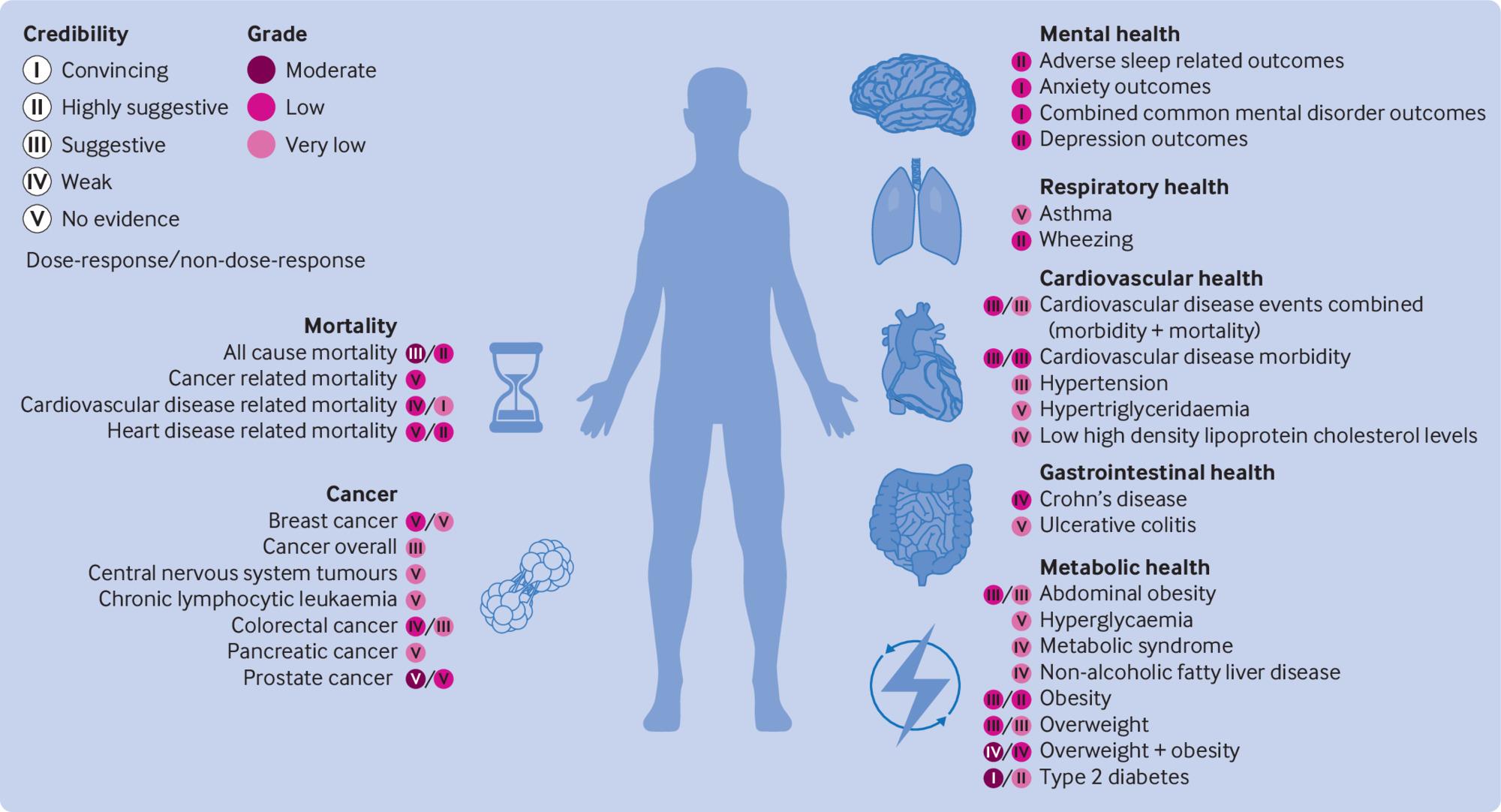

The umbrella review in the BMJ covered 45 meta-analyses from 14 review articles – all published in the last three years – that linked UPFs to adverse health effects. It’s worth noting that none of these were funded by companies that are involved in UPF manufacturing. The researchers graded evidence of health outcomes as convincing, highly suggestive, suggestive, weak, or no evidence.

Convincing evidence indicated that high UPF consumption is linked to a 50% higher risk of death from cardiovascular disease, a 48-53% greater risk of anxiety and other common mental health conditions, and a 12% increased risk of type 2 diabetes. And highly suggestive evidence indicated a 21% higher likelihood of death from any cause, a 40-66% greater risk of death from heart disease, obesity, type 2 diabetes or sleep problems, and a 22% higher likelihood of depression.

Additionally, there was some evidence of links between UPFs and gastrointestinal health, asthma, cardiometabolic risk factors and certain cancers – but the researchers cautioned that the amount of proof for these links was limited.

Dr Chris van Tulleken, a leading expert on UPFs and author of Ultra-Processed People: The Science Behind Food That Isn’t Food – the book that amplified the conversation around UPFs last year – called the findings “entirely consistent” with what is now an “enormous number of independent studies which clearly link a diet high in UPF to multiple damaging health outcomes including early death”.

“We have good understanding of the mechanisms by which these foods drive harm,” he told the Guardian. “In part, it is because of their poor nutritional profile – they are often high in saturated fat, salt and free sugar. But the way they are processed is also important – they’re engineered and marketed in ways which drive excess consumption – for example, they are typically soft and energy dense and aggressively marketed usually to disadvantaged communities.”

Nova classification is flawed when it comes to health impacts

However, experts have pointed out that this is not a one-size-fits-all issue. For starters, Monteiro explicitly discounted nutrition as being relevant to his classification.

“Overall, this only consolidates findings from previous papers that suggest an association between ultra-processed food and disease,” said Dr Duane Mellor, a registered dietitian and senior lecturer at Aston University in England. “As such it still does not answer what is in ultra-processed foods that could be associated with the increased health risks and if any associated increase in risk is seen with all foods classified by Nova as ultra-processed.”

Others have pointed out the limitations of the Nova classification system. Within the review, the authors observe that some UPFs were linked to ill health, but the effect of others – like ultra-processed cereals, dark or whole-grain bread, packaged sweet and savoury snacks, fruit-based products, and yoghurt and dairy-based desserts – was inversely associated, according to food systems consultant Marlana Malerich.

“These products, like breads and cereals, often contain higher amounts of fibre, which, according to the Nova system, wouldn’t technically classify as UPFs,” she said. “It’s crucial to recognise the limitations of the Nova system, which does not account for nutritional content, leading to potential misclassification.”

This is echoed by Jenny Chapman, a Churchill Fellow who authored a study arguing this very point. Her work was focused on plant-based meat, which too is classed as a UPF, and how this association has bred misconceptions about their health impacts.

“Given the widely publicised issues with using such a subjective sociopolitical framework (Nova) I am surprised nutrition scientists are still using a poorly defined categorisation (that considers everything from how a food is marketed to how it is packaged) to attempt to conduct robust epidemiological research,” she told Green Queen. “Without a watertight definition, any science attempted using the Nova classification is going to be of questionable quality.”

She lauded the authors for weighing the studies based on their quality of evidence, but noted: “The report collates a host of cohort studies, which are notoriously difficult to design, conduct and analyse because people’s relationship with food is inherently messy and complicated.”

Chapman explained that the flaw in the food frequency questionnaires reviewed by the BMJ study is that it relies on people remembering what they ate for lunch on a given day, as well as how many grams they consumed, and how the food was processed. This is something the authors also acknowledge as one of the review’s limitations.

“Despite the impressive-sounding headline stats, this review tells us nothing we didn’t already know about food, nutrition and the poorly defined ‘ultra-processed’ category,” she said. “In short: do you drink a lot of sugary soda? You probably should cut down. It does, however, successfully highlight how much interest there is in the topic.”

Other studies show not all UPFs are unhealthy

Chapman did credit the authors for recognising that not all UPFs are bad or unhealthy, that the data doesn’t suggest causality, and that there could be several factors they failed to capture that led to the observations about health effects. This includes socioeconomic elements – scientists have previously argued that UPFs could be necessary to feed the world.

Ultra-processed food is very likely an indicator of an overall higher risk of ill-health,” said Gunter Kuhnle, professor of nutrition and food science at the University of Reading. “For example, in many countries, people with lower income or lower socioeconomic status consume more ultra-processed foods. Many studies also show that people who consume a lot of ultra-processed foods also have an unhealthy lifestyle, and therefore a higher risk of disease. Although many studies attempt to adjust for this, it is virtually impossible to do so completely.”

Last year, a study involving over 266,000 Europeans published in The Lancet added some nuance to the discourse, suggesting that some UPFs can be good for you. Malerich points to a few others. An 18-year-long study from 2021 found that each additional daily serving of UPFs led to a 7% increase in the likelihood of cardiovascular disease. But while bread, processed meat, salty snacks, and low-calorie soft drinks were linked to a higher risk, UPFs like cereals were linked to a reduced risk.

And in 2020 and 2023, two separate studies linked UPFs to depression – but only artificial sweeteners and beverages containing them were significantly associated with depression within the Nova-classified UPF category.

“It is crucial to underscore the complex relationship between diet and health, emphasising the need for advanced dietary guidelines that consider the nutritional diversity within UPFs,” said Malerich. “Many other categorisation systems exist that require more nuance, but offer much more clear guidelines about the health of food.” She cites the Nutri-Score system, used in countries like France, Spain and Belgium as an example. “No system is perfect, but a system that categorises by the level of processing versus the nutritional content is an oversimplification.”