Americans are Buying & Paying More for Sustainably Marketed Products: Report

5 Mins Read

Despite many politicians opposing climate funding – and some denying climate change altogether – a survey of 2,700 Americans shows that people are buying products with sustainability messaging more than conventional ones, as well as paying more for them. When will its leaders catch up?

Americans may have a bad reputation in many quarters, given their leaders’ insistence on ignoring the climate crisis (they’re not the only ones) and the population’s refusal to link what they eat to climate change.

But there are two sides to every coin, and American habits on sustainability are no different, according to a recent survey by New York University’s Stern Center for Sustainable Business (CSB), which found that products marketed sustainably are growing twice as fast as those marketed conventionally while selling at a 28% premium.

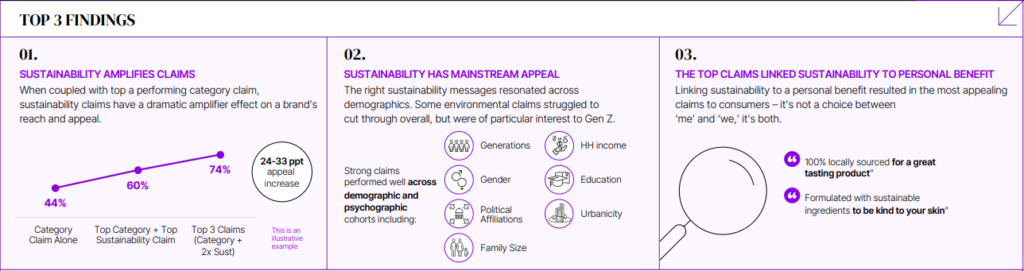

CSB partnered with Edelman and nine brands in the apparel, food and beverage, tech, household items and personal care sectors for the survey, testing how messaging on core product attributes and sustainability fare with customers’ purchasing intent. Across the board, category claims (for example, ‘tastes great’) are crucial and non-negotiable, and adding sustainability messaging to these helps increase brands’ reach.

Consumers want quality first

Americans responded most positively to messaging that talked about personal health benefits (for themselves and their families), individual financial savings, and impact on the immediate world and communities around them. Claims around animal welfare, supporting local farmers, and 100% sustainable sourcing also performed well.

But such messaging worked best when aligned with core attributes. Product quality is key – “nobody wants to buy a laundry detergent that doesn’t clean well, even if it is sustainable”, as researchers Randi Kronthal-Sacco and Tensie Whelan write. People want to know first that the brand is delivering the benefits of the products they’re buying (whether the detergent would clean clothes well, a lotion would moisturise the skin properly, or if a food item tastes good).

The survey found that while honing in on these core attributes alone would appeal to 44% of people, adding two sustainability claims on top would increase their appeal by 24-33 percentage points, with an average of 74% found across the nine brands. In that vein, the most convincing marketing claims could be “good for your skin and the planet” or “100% sustainably farmed for great taste”.”

Interestingly, consumers were less interested in the scientific reasons behind a brand’s eco claims, unless it was tied to a personal reason to care – for example, “reduced air pollution” would be trumped by “reduced air pollution for cleaner air to breathe”. The same goes for recycled packaging: unless it’s 100% recycled packaging, these attributes don’t resonate with people without an additional factor, such as “microplastic-free packaging for human and ocean health”.

People across all demographics in the US are looking to buy products that enhance their quality of life from a sustainability perspective, especially when associated with themselves, their families or their community.

A green gap?

We talk a lot about greenwashing – where companies claim to be eco-friendly but it turns out to just be a facade. But how does it work when it’s the public’s turn? Is there a ‘green gap’ between what consumers say they’ll buy, and what they’ll actually end up purchasing?

CSB partnered with insights firm Circana to evaluate barcode data on 250,000 products in the consumer-packaged goods (CPG) category, dating back to 2013. The analysis found that while sustainably marketed products only made up 17.3% of all CPG product sales, they’re responsible for 30% of the sector’s overall growth.

In fact, one of every two new CPG items sold in 2021 had one or more sustainability attributes. Segments like dairy, yoghurt and toilet paper saw more than 60% of products sell with eco claims. The sustainable market share has kept growing, while conventional products have witnessed deficit growth.

The demographic divide

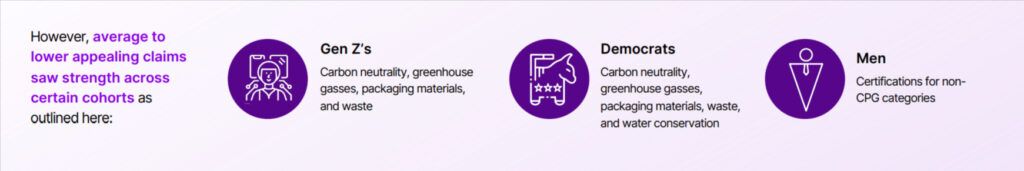

CSB notes that for widely available categories, all demographics buy sustainable products, but there are differences in who buys how much. Younger consumers, for example, over-index on eco purchasing, as do people with higher incomes or education and urbanites.

Gen X, middle-income, suburban and rural Americans also tend to buy products with sustainable claims. But cost and availability constraints mean people with lower incomes or education (up to a high-school education, for example) and retirees buy fewer of these items. But the researchers add: “As we see these products become more available and the premiums decrease, we are likely to see more purchasing from those groups as well.”

They conclude that most Americans would like to purchase products that are healthier, help save costs, protect their children’s futures, improve animal welfare, support local farmers, and are 100% sustainably sourced. “Consumers don’t see it as a political position, and our research finds that Americans are carrying through with that purchase intent,” write Whelan and Kronthal-Sacco.

“Every leader thinking twice about sustainability on the grounds of it being ‘divisive’ needs to know this: if you communicate sustainability the right way, it will appeal across political affiliation, income, gender, education levels, and age groups,” said Edelman CEO Richard Edelman. “Sustainability is an amplifier and if brands embrace it, we can exponentially increase growth and trust.”

“The sustainability amplifier effect is real and can help brands reach and engage more people,” added Kronthal-Sacco. “We hope this mobilises brands and marketers to act and put sustainability at the core of business strategy, innovation, and communications.”

The other group that does need to mobilise is the people who run the country. With a presidential election coming up next year – and greenwashing and climate change more in the spotlight than ever before (rightly so) – the government needs to step up against misleading eco claims and provide a framework for companies to do better by the climate and their consumers.