7 Mins Read

Sparked by the infant formula crisis, the FDA is about to undergo a major overhaul that will transform its human foods programme and regulatory affairs teams – what does this mean for alternative proteins?

In February 2022, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) recalled infant formula products made in an Abbott Nutrition facility in Michigan, after finding they may have been contaminated with Cronobacter sakazakii, which led to four infants being hospitalised, and two dying.

The FDA was roundly criticised for its oversight, not least because it first found out about the issue five months prior to the recall when a baby was hospitalised in September. In fact, in October, a former employee at the Abbott Nutrition facility had flagged concerns about food safety violations with senior FDA officials.

But it took a while for the government agency to take action. When it first heard about the infant being hospitalised in September, its officials were at the plant for an inspection, but didn’t find any serious problems or evidence of the bacterial contamination. In January, however, they returned to find at least five different strains of Cronobacter sakazakii in the facility.

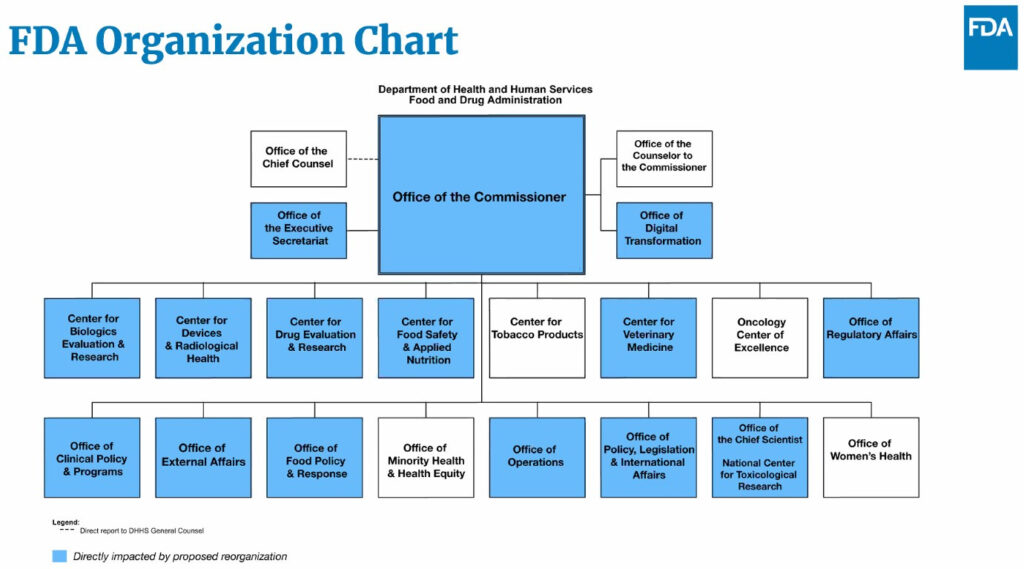

It led to a long review process that will lead to the largest reorganisation of the FDA in history. This will mean an overhaul of the Office of Regulatory Affairs (ORA), which will be renamed and – alongside the Center for Food Safety and Applied Nutrition (CFSAN) and Office of Food Policy and Response – will be bridged under a newly created Human Foods Program.

It is the CFSAN’s Office of Food Additive Safety (OFAS) that is responsible for dealing with regulatory approval of alternative protein products – including cultivated meat and precision-fermented proteins – as well as handing out Generally Recognized as Safe (GRAS) notifications. So how does the reorganisation of the FDA affect alt-protein, if at all?

FDA hopes to ramp up pace and implement changes soon

The slowness and dysfunction of the FDA’s food functions is of little surprise to experts. An investigation by Politico revealed that food regulation is no longer a high priority for the agency, with drugs and medical products dominating both the budget and bandwidth. This has only been exacerbated since the pandemic.

“The food programme is on the back burner. To me, that’s problem no. 1,” Stephen Ostroff, a former FDA senior official who twice served as acting commissioner, told the publication. “There are a lot of things that languish. There’s nobody really pushing very hard to get them done in the same way that you’re pushing very hard to get the Covid vaccines out there and authorised. We don’t have that imperative and that pressure to actually make things happen on the food side of the Food and Drug Administration.”

This slow pace can also be seen in the FDA’s reorganisation itself, which was announced last January, and will still take quite a bit of time. “As a federal agency, the FDA must adhere to the required processes and notifications for reorganisations. Although the proposal has been finalised by the FDA, there are several critical steps remaining before implementation of the new structure can commence,” an FDA spokesperson told Green Queen.

“These include review by the Department of Health and Human Services and the Office of Management and Budget, providing the House and Senate Appropriations Committees with a 30-day notification period, issuing a Federal Register Notice and engaging in all necessary negotiations with Unions representing impacted staff.”

They added that the agency hopes it can begin implementing the proposed changes now, once it completes all the necessary review and approval steps. “The FDA remains committed to keeping the public up to date as the proposal continues to be developed,” said the spokesperson. (They did not respond to specific questions about the OFAS or the regulation and importance of alt-proteins.)

A focus on field-based operations

The reorganisation will see the ORA renamed as the Office of Inspections and Investigations (OII), with an emphasis on lab testing, field-based inspections, investigations, and import operations. It means about 1,500 ORA staff will be reassigned to product centres to work directly on inspections and investigations, with the goal of preventing the duplication of functions at the ORA.

At a recent webinar, outgoing FDA principal deputy commissioner Janet Woodcock said: “We’re really trying to transform different aspects of the FDA to make them more efficient, more effective, and so forth… Our mission seems to continually be broadening and we really do need to be able to meet our mission as much as our resources allow.”

This could potentially mean more frequent and more efficient inspections, which would lead to quicker resolutions and increased vigilance from companies too. In fact, businesses will need to adapt to the structure, as the FDA will likely be better equipped with investigators who are more specialised in specific product areas. In-house regulatory affairs and quality assurance staff should be well-versed with the new setup, while companies need to be aware of any updated compliance expectations and identify any new points of contact.

As for the CFSAN, its cosmetics regulation and colour certification functions will be transferred to the Office of the Chief Scientist, a move that is said to recognise the evolution and innovation in this product space, and better align the agency’s cosmetics subject matter experts with the Chief Scientist, who is “focused on research, science, and innovation that underpins the agency’s regulatory mission”.

What this means for alt-protein

The implications for alt-protein are less clear. The FDA has previously issued GRAS notifications for UPSIDE Foods and Eat JUST’s respective cultivated chicken products, as well as ‘no questions’ letters to precision fermentation companies Perfect Day, The EVERY Co, Remilk and Imagindairy.

Shannon Cosentino-Roush, president of the Association of Meat, Poultry and Seafood (AMPS) Innovation – a US alliance dedicated to cellular agriculture – expressed hope that the reorganisation won’t lead to “delays or a departure from FDA’s leadership” in advancing novel food technologies. “The industry remains committed to supporting the agency and this transition by advocating for [the] FDA to receive the resources it needs not only to achieve its mandate, but to ensure the US stays at the forefront of innovative advancements that are critical for American competitiveness, food security, and sustainability priorities,” she told Green Queen.

“Key among this is ensuring that the cell-cultured consultative process is robustly staffed to reduce delays in the review process that could impede progress, especially when the industry is rapidly advancing from R&D to commercialisation and is fuelled by start-up companies aiming to demonstrate commercial viability for this technology. We applaud [the] FDA for making efforts to strengthen its food program, and we share the agency’s goal of providing safe products to consumers,” Cosentino-Roush added.

A spokesperson for the Precision Fermentation Alliance (PFA), the US-based industry association, said that while it’s too early to comment, they expect the agency to continue to be a global regulatory leader for novel foods.

It’s a common sentiment that the FDA is stretched for resources, given its wide remit. “We are very strong supporters of further funding the FDA,” said the PFA representative. “We would hope a significant portion of these funds would be directed to the Office of Food Additive Safety, which handles GRAS reviews for the agency so that it can continue to build its scientific teams and carry on the high-quality reviews and timelines that have made the FDA the gold standard.”

Along similar lines, Laura Braden, associate director of regulatory affairs at alt-protein think tank the Good Food Institute (GFI), added: “GFI appreciates the cooperative approach FDA has taken in working with companies in the alternative protein industry to bring their products to market safely. As the agency reorganises its food regulation structure, adequate funding for FDA that allows it to stay at the forefront of scientific research and regulatory approaches is crucial for fostering an environment where safe innovation in the food sector can thrive.”

Cosentino-Roush acknowledged that the FDA’s approval of UPSIDE Foods and Eat JUST’s cultivated meat products “sent reverberations globally”, signalling that cultured proteins moved “beyond theory and into reality”. “As [the] FDA embarks on its reorganisation and shift in leadership, AMPS Innovation underscores the importance of maintaining the momentum and prioritisation of the cell-cultured consultative process, which serves as the backbone of the regulatory pathway to market for this key, innovative, and advancing industry,” she said.

“In 2024, we hope to see additional ‘no questions’ letters issued for other cell-cultured meat and fish products, bringing a range of new choices to market.”