US Banks Have Provided $134B in Livestock Funding Since 2016, With Nestlé & ADM Biggest Beneficiaries

6 Mins Read

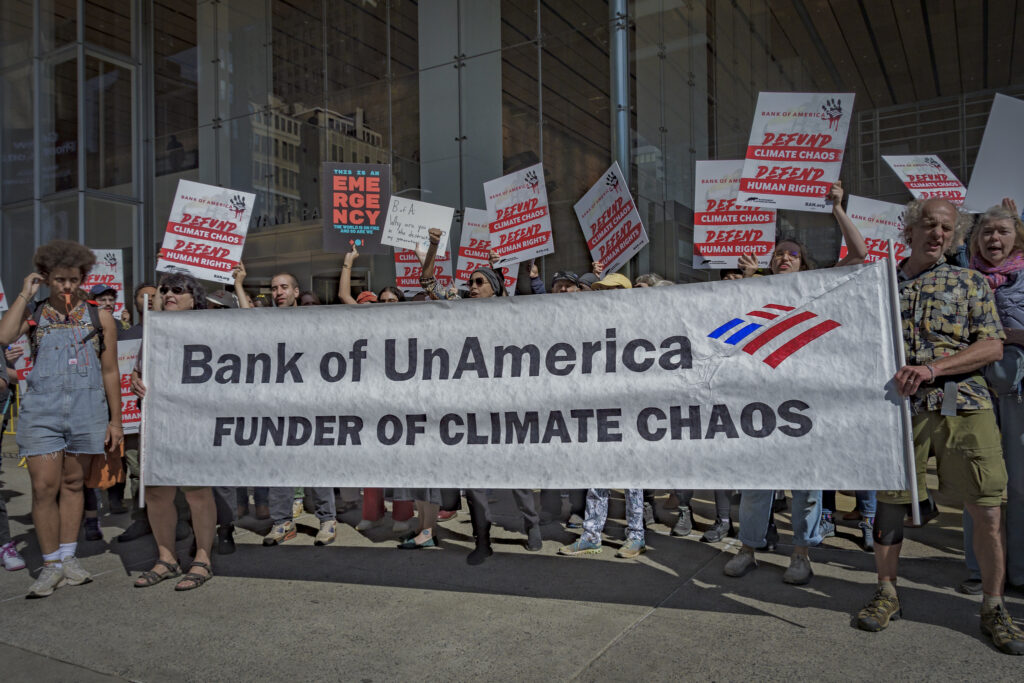

Despite net-zero plans, banks in the US are fuelling the expansion of industrial livestock production by financing corporations whose emissions are higher than all of Japan, according to new research.

A total of 58 US banks provided $134B in financing to meat, dairy and animal feed corporations between 2016 and 2023, with just three making up more than half of this sum – going against their climate commitments.

That’s according to research by Profundo and climate NGO Friends of the Earth, which analysed American banks’ financing of the 56 largest livestock companies in the form of investments, loans, and underwriting (such as share and bond issuance guarantees). Titled Bull in the Climate Shop, it follows a similar study from last month, which revealed that banks and financial institutions have credited livestock producers with $615B to increase meat and dairy production since the Paris Agreement.

Profundo and Friends of the Earth found that Bank of America, Citigroup and JPMorgan Chase were responsible for 55% of this funding, amounting to $74B. Dubbed the Big Three, they’re the largest US-based lenders to animal protein producers, and three of the top four global debtors to these corporations. Nestlé is the largest beneficiary of these banks’ financing ($19.2B), followed by ADM ($15.6B).

But the Big Three’s lending to these companies represents just 0.25% of their total outstanding loans, but roughly 11% of their report financed emissions – that’s 44 times higher. It presents an outsized obstacle to banks meeting their climate commitments: the three banks have all committed to reducing emissions linked to client financing and reaching net zero by 2050.

“Banks have committed to pathways to net zero, but they are ignoring a huge ‘cow-shaped hole’ in their plans,” said lead author Monique Mikhail, who is the director of Friends of the Earth’s agriculture and climate finance programme. “Big Meat and Dairy exerts a vastly disproportionate impact on the banks’ total emissions, putting their own stated climate commitments at risk.”

The Big Three’s big climate footprint

In 2022, the financing of these 58 banks was linked to about 63.1 million tonnes of greenhouse gas emissions – about the same as Austria’s total emissions in 2020. The Big Three are responsible for 39% of these, which is the equivalent of the exhaust from 5.4 million cars driven for a year. Bank of America was associated with the largest climate footprint, followed by Citigroup and JPMorgan Chase.

Cargill, ADM, Bunge, Nestlé and JBS are some of the worst offenders, given their roles in meat, dairy and feed production, and in large part due to their high scope 3 emissions (which are ‘indirect’ emissions from activities linked to a company’s operations). In fact, the former four companies make up the bulk of financed emissions from all three banks – 76% for Bank of America, 92% for Citigroup, and 86% for JPMorgan Chase.

The report also assessed the banks’ emissions intensities – emissions per million dollars in outstanding loans – to highlight the disproportionate contribution of livestock production to their portfolio, compared to other high-emitting sectors. For example, dollar for dollar, Bank of America and Citigroup’s livestock emissions intensities are twice that of auto manufacturing, and JPMorgan Chase’s contribution is four times higher than auto manufacturing and nine times more than operational oil and gas.

“Our research finds that by eliminating their financing of high-emitting corporations involved in meat, dairy, and feed production – a relatively small change in how they allocate their capital – these big banks can affect a sharp emissions reduction,” said study co-author and senior financial researcher at Profundo, Ward Warmerdam. “According to our research, defunding industrial livestock production is one of the most climate-positive choices these banks could make.”

Livestock emissions may be four times higher than reported

Livestock farming currently emits between 11-19.5% of the planet’s total emissions. It’s estimated that this sector will comprise roughly half of the global 1.5°C emissions budget by 2030, and 80% by 2050. The Bull in the Climate Shop study shows that the 56 largest corporations in this industry produce more emissions than Japan, the world’s eighth largest polluter.

However, the true extent of their contributions to banks’ emissions may remain obscured even to the banks themselves, because these corporations commonly underreport their emissions. The report suggests their actual emissions may be four times higher than self-reported figures. Despite banks acknowledging that full greenhouse gas emissions disclosures are crucial for good financial decisions, only 22% of companies analysed in the study disclose their scope 3 emissions. Meanwhile, 56% don’t report any emissions at all.

Scope 3 emissions can make up 90% or more of agricultural companies’ emissions – for Nestlé, the second largest dairy processor, these account for 95% of its emissions. The world’s largest meat company, JBS, declined to disclose Scope 3 emissions from the ‘purchased goods and services’ category, despite its sourcing of livestock and poultry from over 50,000 producers comprising 97% of its climate footprint.

These gaps in emissions reporting are misleading financiers about the associated climate risks. When calculating emissions based on the production data – rather than self-reported information – the picture becomes clearer. Bank of America’s total livestock-associated emissions are more than those of Citigroup and JPMorgan Chase combined. This is driven by its relationships with JBS and Canadian dairy company Agropur, together accounting for 60% of Bank of America’s emissions.

The impact of methane, and what banks must do

The researchers call methane – a gas 28 times more potent than carbon – the “Achilles’ heel of banks’ net-zero ambitions”. The livestock sector is responsible for a third of global methane emissions, which is roughly the same as oil, coal and natural gas combined. The gas accounts for nearly half of the 58 banks’ financing-linked emissions from meat and dairy clients.

Methane makes up the bulk of industrial livestock emissions, which is why making reductions in related emissions is key for banks that have committed to aligning their portfolio with a net-zero pathway. When it comes to the Big Three, Bank of America again has a higher methane footprint than the other two combined, ascribed to its financing of “methane bombs” like JBS (which made up 87% of the bank’s methane emissions).

JPMorgan Chase has already acknowledged the importance of addressing methane, noting that “investors, policymakers, insurance providers, and non-governmental organisations, are recognising that reducing methane emissions is a pragmatic opportunity and are beginning to take action”. But it has ignored the contribution of industrial livestock, instead focusing on oil and gas clients for methane reduction strategies. Likewise, Citigroup and Bank of America are yet to address methane emissions from animal agriculture, signalling a major gap in the Big Three’s climate commitments.

The authors recommend US banks halt all financing that enables industrial livestock expansion. This means no issuance of new financing or revolving credit facilities to corporations in this space, no renewals of existing loans or facilities, no underwriting of bonds, IPOs or secondary offerings, and no investment in publicly traded companies.

Banks should also require meat, dairy and feed clients to disclose 1.5°C-aligned targets and action plans verified by an independent third party. At a minimum, this entails disclosing 100% of their emissions across all scopes, setting short- and long-term reduction targets, prioritising methane cuts of at least 30% by the end of the decade, and achieving these by reducing the number of animals in the supply chain, not relying on offsets or credits (which don’t really work).

The authors expand on that last point by urging banks to address the social and climate harms of industrial livestock production by mandating companies to halt deforestation and biodiversity loss, respect human and labour rights, adopt a zero-tolerance policy for violence against human rights, land and climate activists, establish a robust grievance mechanism, and implement strong animal welfare criteria.

“The data is clear: climate risk is financial risk,” the report concludes. “For each bank, further diminishing an already small proportion of their lending portfolio would reap outsized emissions reduction benefits and propel them toward meeting their climate commitments.”