Hidden Costs of the Global Agri-Food System Add Up to $12.7 Trillion a Year – UN FAO Report

6 Mins Read

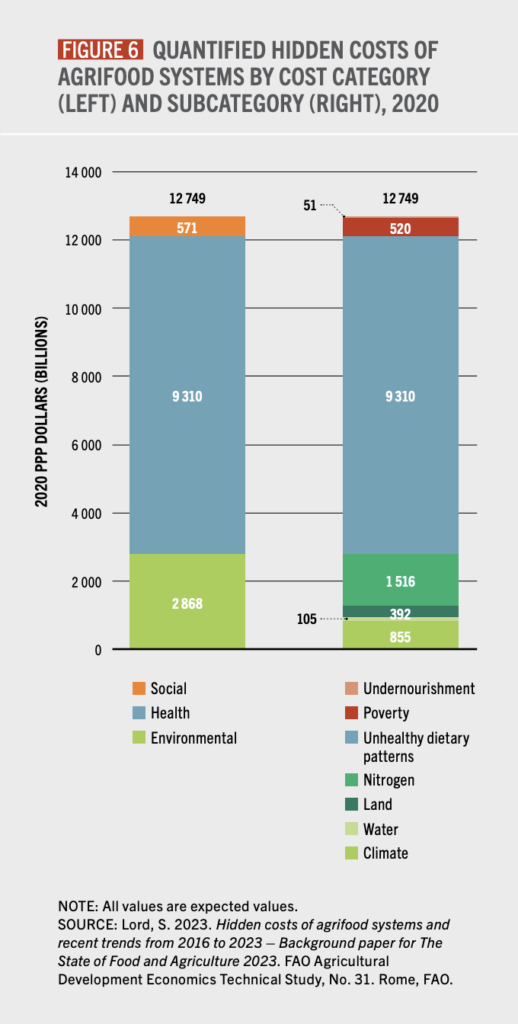

Hidden costs in the global food system amount to $12.7T a year according to a new report by the UN’s Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO). Covering 154 countries, The State of Food and Agriculture found that 70% of the costs are health-related, while a quarter are associated with the environment, and low-income countries are the hardest hit.

The UN FAO has published its flagship report, The State of Food and Agriculture, which has revealed that the hidden costs of the global agrifood system equate to $12.7T – about 10% of the world’s GDP. Even if you take uncertainties into account, there’s a 95% chance that the food industry costs $10T or more, which highlights “the undeniably urgent need to factor these costs into decision-making to transform agrifood systems”.

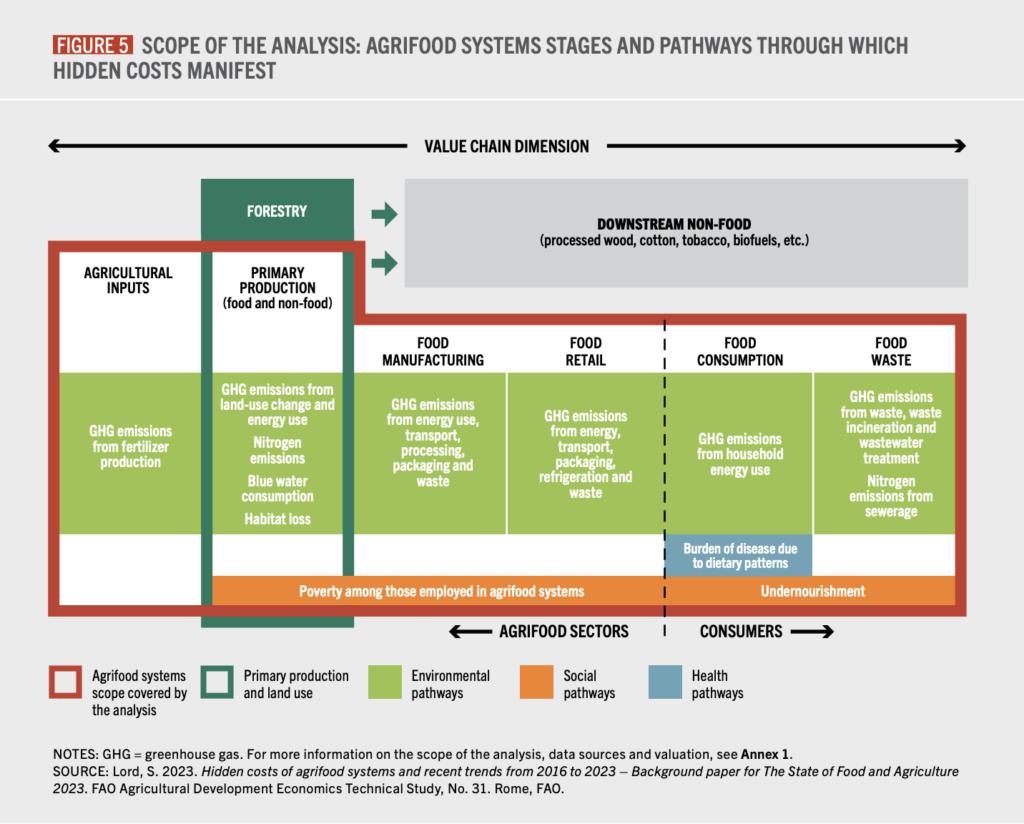

The report argues that while the value of agrifood systems is undeniable – “they provide nourishment, sustain economies and shape cultural identities” – their health, environmental and social impact should not be discounted. The true costs calculated represent failures at market, institutional and policy levels, and the report proposes a two-phase assessment: the first step is to rely on national-level true cost accounting to raise awareness, followed by in-depth and targeted evaluations to prioritise solutions and transformative actions (which will be the focus of the 2024 report).

The FAO’s calculated costs use 2020 purchasing power parity (PPP) dollars, which is a method to compare living standards for countries with varying incomes and prices.

Health is the biggest driver of food’s hidden costs

The largest hidden monetary impact comes from health: 73% of the quantified hidden costs in 2020 were linked with dietary patterns that led to obesity and non-communicable diseases, which caused labour productivity losses. These health-related costs, which equate to over $9T in 2020 PPP dollars, are driven by diets high in ultra-processed foods, processed meat, saturated fat, sodium and sugar, and negatively impact the economy.

But the consumption of unhealthy diets can be attributed to a lack of economic or physical access to nutritious foods. One study found that healthy diets were out of reach for about three billion people, with another estimate revealing that up to one billion were at risk of losing access to healthy diets if a shock to real incomes occurred.

The health-related costs vary considerably from country to country but are most prominent in high- and middle-income countries. “This points to the need to promote healthier diets and environmental stewardship in high-income countries, the report reads. “In many of these countries, policies and investments already target environmental issues, but there is much less focus on diets, as these often come down to personal choice and preference, which are more difficult to regulate or shift.”

Environmental costs amount to 20%, but this may be an underestimate

Environmental factors account for 20% – or $2.9T – of the total hidden costs, a number the FAO says is likely an underestimation. These factors include greenhouse gas emissions along the entire food value chain, including the climate costs of food and fertiliser production and energy use; nitrogen emissions at primary production levels and from sewerage; blue water use that causes scarcity, agricultural and labour productivity losses and undernourishment; and land use change at farms that lead to ecosystem degradation.

More than half (52%) of the environmental costs were linked to nitrogen emissions, mostly from runoff to surface waters and ammonia emissions to air. This was followed by GHG emissions (30%), land use change costs (14%) and water use (4%). These costs affect all income groups and countries, but lower-income nations bear twice the cost compared to middle- and higher-income ones.

The report comes weeks after an investigation by the Guardian revealed that officials at the FAO were censored and undermined by the UN body when reporting on the methane emissions caused by the animal agriculture industry. The organisation’s leadership attempted to water down the link between livestock farming and climate change in subsequent reports, leading to concerns from scientists about the continued decline of the FAO’s estimate of animal agriculture’s overall emissions.

Richer countries generate hidden costs, poorer ones suffer

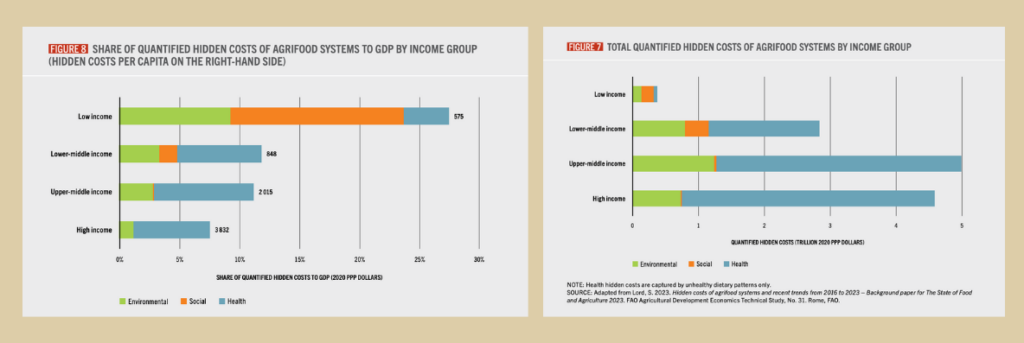

The above point is true to a larger extent. There is a stark contrast between the impact of the food system’s hidden costs on different countries. These true costs account for more than a quarter (27%) of the GDP of low-income countries, primarily due to the effect of poverty and undernourishment. In comparison, these costs amount to 11% and 8% of the GDPs of middle-income and rich countries, respectively.

In fact, poverty and undernourishment account for half of the total hidden costs in poor countries, and addressing these issues is a key priority. The FAO suggests that the incomes of “the moderately poor working in agrifood systems” must increase by 57% on average in low-income countries and 27% in lower-middle-income countries to ensure they’re above the moderate poverty line, which would help reduce food insecurity and undernourishment.

The problem, as you might have guessed, is that these countries aren’t the major contributors to these hidden costs. Upper-middle-income countries generate 39% (or $5T) of these costs, high-income nations are responsible for 36% ($4.6T), and lower-middle-income ones account for 22%. On the other end of the spectrum lie the poorer countries, which only contribute to 3% of the overall costs.

In middle- and higher-income countries, productivity losses from dietary patterns are the biggest contributor to agrifood system damages, followed by environmental factors. For low-income nations, it’s the social aspects of undernourishment and poverty.

Calling on governments to adopt true cost accounting

“Finding that unhealthy dietary patterns are the main contributor to global hidden costs should not steer attention away from the environmental and social hidden costs. Rather, it emphasises the importance of repurposing support to transform agrifood systems to deliver healthy and environmentally sustainable diets to all,” the report says.

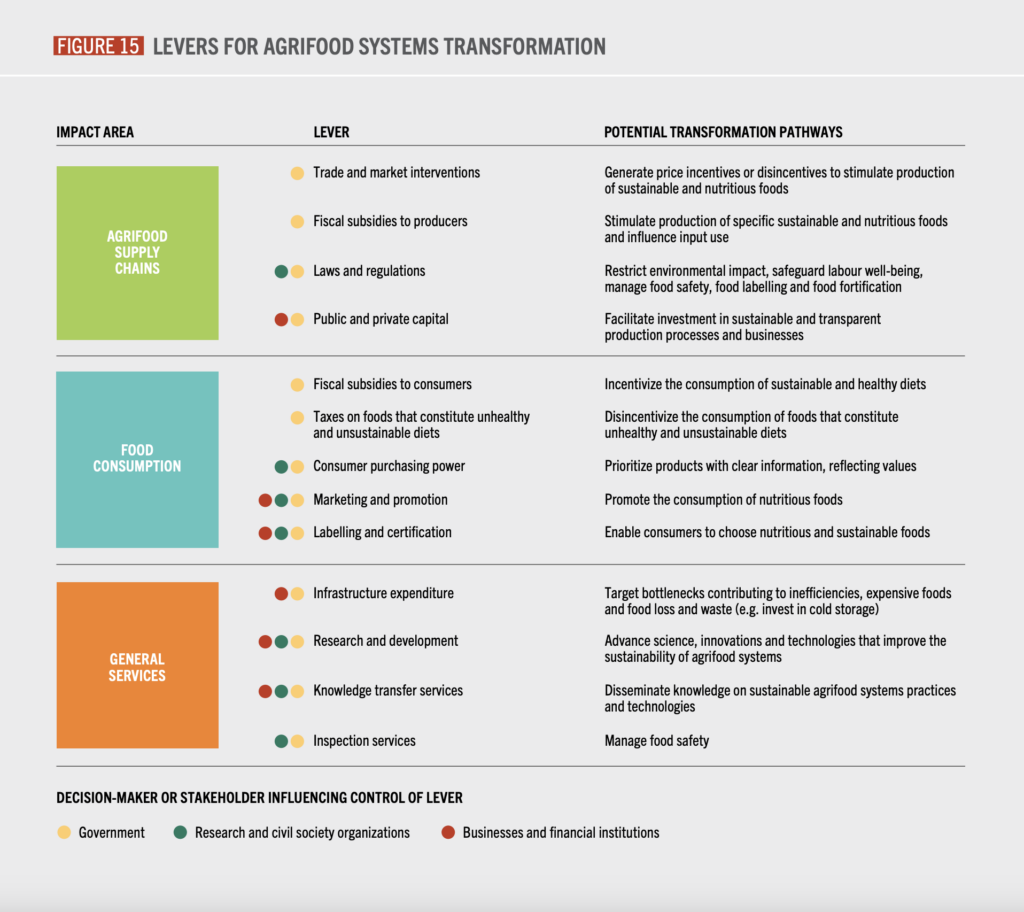

The FAO is now calling for more regular and detailed analysis by governments via true cost accounting to help transform agrifood systems and address climate change, poverty, inequality and food security. As mentioned above, next year’s report will focus on targeted assessments to identify the best mitigation measures, which could include governments pulling levers to adjust agrifood systems, such as taxes, subsidies, legislation and regulation.

In a separate report by nonprofit ClimateWorks, it was revealed that wealthy people and foundations globally donated between $8-12B for climate change mitigation last year. But this number is only 1.6% of the total donations made by philanthropists in 2022, which reached $811B. As mentioned in the HEATED newsletter, this is the opposite direction of where we need to be heading.

“The intensifying climate crisis demands greater ambition, scale, and urgency to safeguard lives. There has been meaningful climate progress, but maintaining the status quo is not enough, and that includes philanthropy,” said ClimateWorks CEO Helen Mountford. It points to the need for increasing investment and attention not just from governments, but the rich – given that it’s the wealthier who generate hidden costs the most.

FAO director-general Qu Dongyu said: “In the face of escalating global challenges: food availability, food accessibility and food affordability; climate crisis; biodiversity loss; economic slowdowns and downturns; worsening poverty; and other overlapping crises, the future of our agrifood systems hinges on our willingness to appreciate all food producers, big or small, to acknowledge these true costs, and understand how we all contribute to them, and what actions we need to take.”

He added: “I hope that this report will serve as a call to action for all partners – from policymakers and private-sector actors to researchers and consumers – and inspire a collective commitment to transform our agrifood systems for the betterment of all.”