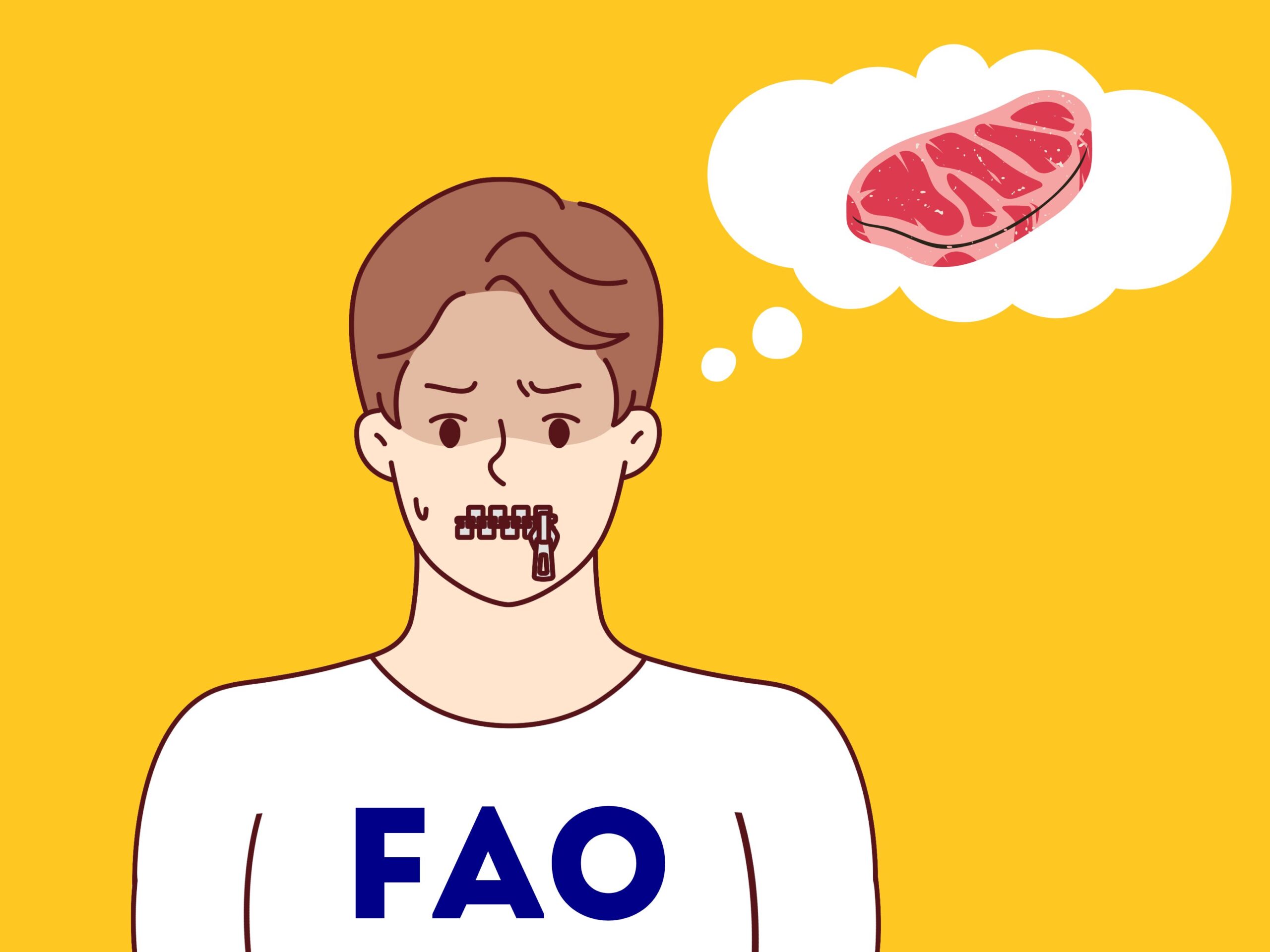

Why Won’t the FAO Talk About Meat? It’s What Climate Experts are Asking the UN Body

9 Mins Read

At COP28, the UN Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) produced its much-awaited roadmap to cut emissions from the food system in line with the 1.5°C goal – but it didn’t address reducing meat and dairy consumption as a solution. Now, academics and experts are asking why.

What will it take for the FAO to talk about the impact of meat? That’s the question on the minds of eight experts who have published a comment in the Nature Food journal, criticising the UN body’s failure to include the reduction of meat and dairy and dismissing alternative proteins in the food systems roadmap it presented at the climate summit in Dubai late last year.

The FAO had outlined 120 actions to meet 20 key targets, with measures including cutting methane emissions from livestock by 25% and halving food waste by 2030. While the report acknowledged that we “absolutely must” change diets to reduce emissions, it suggested that plant-based foods can’t be an adequate source of certain nutrients. It actually promoted the increase of aquaculture by 75%, and said meat production needs to be increased in lower-income countries to address health challenges.

Before the conference, there was talk that the roadmap would ask rich nations to eat less meat. But ultimately, the report did not call on higher-income countries – which already consume way more meat than recommended – to cut their meat intake. In response, a group of organisations including ProVeg International, Mercy for Animals, Friends of the Earth, Changing Markets Foundation, as well as Green Queen, highlighted the gaps in a joint letter.

“The roadmap falls short of highlighting the specific benefits of transitioning towards more healthy, plant-based diets, especially in regions with excessive consumption of animal-based foods,” said Stephanie Maw, policy manager at ProVeg.

“I call this approach guillotine syndrome. There might be a slight improvement in efficiency, but it’s still decapitation,” climate journalist George Monbiot wrote in his Guardian column. “Following the report it published this week, I feel I can state with confidence that the FAO is a major cog in the meat misinformation machine.”

Now, four months on, academics from the Stockholm Environment Institute, Pratt Institute and New York University in the US, the Institute of Environmental Sciences and Utrecht University in the Netherlands, and the Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina in Brazil have questioned the FAO’s disregard for alternative proteins and ignorance of meat and dairy consumption in its climate messaging.

Meat and dairy reduction among the most ‘obvious’ climate solutions

“The FAO roadmap neglects one of the most obvious and urgent interventions to reduce emissions from the food system: shifting away from the production and consumption of animal-sourced foods,” writes the letter. Estimates suggest that animal agriculture accounts for about 11-19.6% of all greenhouse gas emissions. It’s a point of contention, and one that the FAO has been under heavy fire for after it emerged that it has historically watered down the impact of livestock farming in its emissions reporting due to pressure from lobby groups.

While the food system is responsible for over a third of all emissions, meat alone is responsible for 60% of this share, which is twice as high as the emissions of plant-based foods. “The roadmap does not offer measures or milestones for lowering production and consumption of animal-sourced foods, which could yield meaningful emission reductions, particularly in regions where the consumption of such foods is currently high,” the authors write.

They point to research revealing that a shift to plant-based diets that reduce animal consumption can substantially help us meet our climate goals. The roadmap calls for a 1.7% annual growth in the total factor productivity of livestock by 2050, but recent analysis has shown that even ambitious technological improvements to farmed animal management won’t be enough to meet methane reduction targets.

Plus, eating and producing fewer animal-sourced foods can free up land for reforestation and carbon capture and storage. “If freed-up land from a protein transition was used for reforestation, it could remove carbon while generating wider environmental benefits, such as reduced pollution and additional land for biodiversity preservation and restoration,” the experts state, adding that using this land for carbon capture can help avoid “agricultural expansion into natural areas as well as food competition, while removing even more carbon than reforestation in many locations”.

The roadmap suggests that the GHG footprint of aquatic food systems is low, despite the emissions of farmed shrimp being higher than the same amount of chicken. “Any expansion in the sector must be approached with nuance, differentiating between sustainable approaches and approaches that may need curtailing to meet climate goals,” note the authors.

“By failing to recognize the need to reduce the production and consumption of animal-sourced foods, the FAO misses a central element of a climate-friendly food system,” said lead author Cleo Verkuijl, who is a researcher at the Stockholm Environment Institute. “It’s like publishing a 1.5°C roadmap for the energy sector that ignores the need to scale back fossil fuels.”

Concerns about the One Health approach

The experts also criticised the FAO’s failure to acknowledge the One Health approach – which combines human, animal and environmental health – despite the FAO supporting its implementation alongside bodies like the World Health Organization, the World Organisation for Animal Health, and the UN Environment Programme (UNEP).

“Notably, some of the roadmap’s proposed interventions, such as transitioning from beef to chicken and intensifying animal agriculture, could maintain or even substantially increase risks of anti-microbial resistance and/or zoonotic disease,” the comment notes. “This is because farmed land animals are fed high levels of antibiotics, can harbour and transmit potentially highly pathogenic viruses, are bred and kept in large populations, and are kept in close proximity to humans: some of these risk factors are likely more pronounced for conventional poultry farming than cattle farming. Additionally, keeping farmed animals in close quarters can contribute to infectious disease emergence.”

Research has shown that around 94% of all animals on the planet live on factory farms, with at least 100 billion animals killed each year for meat and other animal-derived products for humans. In the US alone, nearly all chickens, turkeys and pigs are kept in concentrated animal feeding operations, as are 70% of cows.

“One Health also includes animal welfare as an important component,” the authors say. “Intensifying animal farming, as recommended in the report, can potentially lead to overcrowding and restrict natural behaviour, which could harm animal welfare. Furthermore, substituting beef with chicken and expanding aquaculture is expected to increase the number of terrestrial and aquatic animals in intensive farming.”

While the roadmap does recognise these risks and emphasises that productivity should be boosted while avoiding “adverse consequences… stemming from the concentrated housing of animals coupled with excessive antibiotic use”, but this may prove challenging and present trade-offs. “The FAO fails to present any methods or concrete data behind their claim that incremental tweaks in farmed animal management alone can meet our climate goals,” said co-author Matthew Hayek.

“Shifting to more plant-based foods, including alternative proteins, is a promising solution to help reduce the risks of zoonotic disease emergence and antimicrobial resistance associated with conventional animal-sourced food,” the commentary suggests.

Experts ask the FAO to embrace alternative proteins

That last bit is a key focus for the authors. Estimates suggest that vegan diets can cut emissions, water pollution and land use by 75%, and that replacing half the amount of meat and dairy with plant-based alternatives can halt deforestation, improve food security and double overall climate benefits.

The academics mention the EAT-Lancet Commission’s planetary health diet recommendations, which suggest a 50% cut in meat consumption globally, and a higher intake of legumes, nuts and whole grains in countries across all income scales. “These under-consumed plant-based foods are associated with improved food security and nutritional outcomes and have far lower GHG emissions per unit kilogram, calorie and protein than meat,” they note.

But Verkuijl said it’s “really surprising” that the FAO roadmap “completely dismisses” alternative proteins like plant-based meats, which it says “have nutritional deficiencies” without any supporting evidence. The authors suggest that the next instalments of the organisation’s plan should incorporate the EAT-Lancet Commision’s recommendations or outline the changes needed globally for healthier, low-emission diets “to explore the nuance of these shifts at a regional and country level”.

The commentary also notes the impact of a shift to plant-based eating on the 1.5°C target. “Across all GHGs, global adoption of a healthy plant-rich diet could reduce emissions enough to bring global average temperatures down by between 0.19°C and 0.36°C cumulatively through to 2100.”

This is why it’s imperative the FAO acknowledge the importance of alternative proteins for a planet-friendly future. Its colleagues at the UNEP have already done so, producing a landmark report during COP28 that endorsed these novel foods’ potential to reduce emissions, land degradation, water and soil pollution biodiversity loss, and zoonotic disease and anti-microbial resistance risks, in direct comparison to animal-derived foods.

And just last week, a survey of over 200 climate scientists and food experts found that a majority think livestock emissions must peak by next year, and be halved by 2030 to align with our climate goals, and to do that, countries of all income levels need to eat more plant-based foods, which were outlined as a ‘best available food’ for better health and climate outcome.

The FAO hits back at criticism

The authors call for the next instalments of the FAO roadmap to be more transparent and vetted by environmental and health experts, which would allow for its recommendations to be assessed against scientific research that has proven reducing meat consumption in rich countries is beneficial for human and planetary health. They note that achieving a climate-friendly food system will require an “unprecedented amount of ambition involving the scaling down of emissions-intensive activities and increased investment in more sustainable approaches”.

“This includes a deep exploration of the opportunities to decrease both the production and consumption of animal-sourced foods. This can include the investigation of solutions like alternative proteins, or scaling up behavioural interventions that improve the accessibility and desirability of culturally appropriate, plant-rich diets. These approaches could offer meaningful emission reductions while presenting other co-benefits, analogous to renewable energy investments in the energy sector,” the comment suggests.

The FAO, for its part, has hit back at the scrutiny, alleging that the authors didn’t make “a proper assessment of the report and its ideas”. David Laborde, director of the FAO’s agrifood economics and policy division, told the Guardian: “We stress the importance of dietary shifts from the first pages of the report, underscoring how this issue is often overlooked.” However, while dietary change is mentioned eight times in the 50-page summary report, reducing meat or dairy consumption is not addressed.

“The changes in diets should not be oversimplified but based on science and evidence. Importantly, meat is only one of the elements in the evolution of diets and limiting discussions to the meat issue is not helpful,” Laborde said. He explained that a methodology, authors’ list and the term ‘One Health’ were all mentioned in the full report, which is not available online. He also suggested that the report didn’t dismiss alternative proteins: “We just firmly believe that betting on one miracle solution to solve the problem is not realistic.”

But Hayek summed the issue up. “With all that food systems are trying to accomplish in the next couple of decades, there are a lot of needles that need to be threaded: increasing food provision while decreasing greenhouse gas emissions, and increasing health and nutrition while decreasing disease risks, foodborne illnesses and pandemics,” he told the Guardian.

“Across the board, [cutting animal product consumption] widens the eye of those needles. To disregard that major opportunity for multiple co-benefits across climate, food security and health is just bewildering, and their reasons for omitting that are opaque.”

The FAO has a long history of downplaying the effects of animal agriculture. But due to its impact, the world is burning, the demand for food is growing, and humans are dying – how long can the food organisation of the United Nations ignore it?