The Complete Ultra-Processed Foods and Plant-Based Meat FAQ Guide: Everything You Need To Know

Are plant-based meats healthy? Are meat alternatives overly processed? Can plant-based meats be part of a balanced diet? All these questions and more are answered in this comprehensive, fact-based, science-backed FAQ guide about Ultra-Processed Foods and Plant-Based Meat.

Introduction

In a world flooded with dietary information via news outlets, ad-hoc influencers and rampant social media-fuelled misinformation, navigating the nuances of ultra-processed foods (UPF) and plant-based meat can be daunting. In the context of a global climate crisis, many people are evaluating the foods they consume and looking to make more conscious choices, ones that have a small environmental footprint. Plant-based meats have become a much-discussed group of foods in the realm of sustainable diets.

In the past few years, a media shift describing plant-based meats as ultra-processed foods, thus portraying them as unnatural and, consequently unhealthy, has left individuals overwhelmed by misconceptions and health uncertainties. Plant-based meats are notably absent from many prominent studies on UPF and health, making discussions on this topic more challenging. Finally, it is not just plant-based meats that fall into the UPF category. Other UPF include wholemeal bread, smoked tofu, wholegrain muesli, vegetable spreads, and nutrient-enriched soy and oat drinks, all of which could be considered healthy, further adding to the confusion. On the other hand, less processed foods like sugar, butter, and cheese may warrant closer scrutiny, despite not being classified as UPF.

Presented below is a detailed Q&A guide designed to provide a well-rounded understanding of UPF and plant-based meat by examining the current evidence and providing accurate, balanced, science-backed insights. The overall aim of this guide is to help readers make informed, health-conscious, and sustainable dietary decisions.

FAQ Resource

What are Ultra-Processed Foods aka UPF?

The term UPF is incredibly ambiguous, with varying meanings depending on who you ask. Even the health experts and food industry specialists lack consensus. Let’s explore insights from some of the most authoritative sources.

The Nova classification system is the most widely used and applied UPF definition and serves as the foundation for the majority of the definitions given by government bodies and international organisations, so let’s start there. Dr. Carlos Monteiro, the mind behind the Nova system, defines UPF as “formulations mostly of cheap industrial sources of dietary energy and nutrients plus additives, using a series of processes (hence ‘ultra-processed’)”.

He elaborates, “All together, they are energy-dense, high in unhealthy types of fat, refined starches, free sugars and salt, and poor sources of protein, dietary fibre and micronutrients. Ultra-processed products are made to be hyper-palatable and attractive, with long shelf-life, and able to be consumed anywhere, any time. Their formulation, presentation and marketing often promote overconsumption.”

The Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO) and the Pan American Health Organisation (PAHO) echo this sentiment in their respective reports, with the latter emphasising that UPF products epitomise inventions of modern industrial food science and technology, often devoid of whole foods, and are ready-to-consume or heat, requiring minimal culinary preparation. Despite this characterisation, the PAHO report acknowledges certain processing methods that enhance diet quality and contribute to extending food availability by overcoming seasonal limitations.

The UK, on the other hand, has no agreed definition of UPF. As stated by the UK’s Scientific Advisory Committee on Nutrition (SACN), “The observed associations between higher consumption of (ultra-) processed foods and adverse health outcomes are concerning – however, the limitations in the Nova classification system, the potential for confounding, and the possibility that the observed adverse associations with (ultra-) processed foods are covered by existing UK dietary recommendations mean that the evidence to date needs to be treated with caution.”

Therefore, understanding what qualifies as UPF requires a deeper exploration of the Nova food classification system, as well as some of the alternative classification systems.

What is the Nova Food Classification System?

To navigate the Ultra Processed Foods debate, understanding the Nova classification system is essential.

Established in 2009 by Brazilian researchers led by nutrition and public health professor Dr. Carlos Monteiro, this system categorises all foods and food products into four groups. Since its establishment, the Nova (‘Nova’ meaning ‘new’ in Portuguese, not an acronym) system has been utilised world-wide to identify and categorise food according to its level of industrial processing.

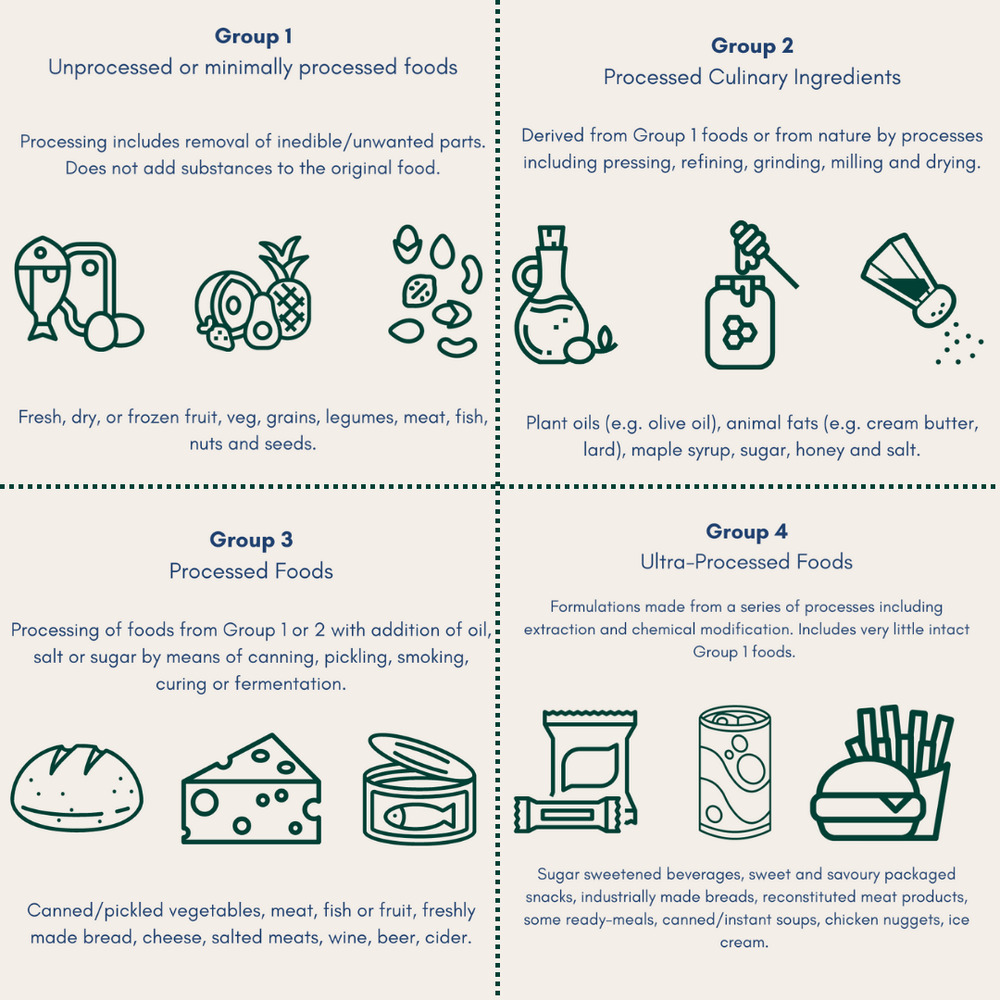

Within the Nova system, Group 1, ‘Unprocessed or Minimally Processed Foods,’ includes items like fresh and frozen vegetables, cuts of meat, and milk. Group 2, ‘Processed Culinary Ingredients,’ contains products that have undergone pressing, refining, grinding, milling, and drying, such as plant oils (e.g., olive oil), butter, and honey – such products/ingredients that are usually not eaten on their own, but are used in the process of cooking. Group 3, ‘Processed Foods,’ items are often ready to heat or consume and are recognisable as modified versions of Group 1 foods, such as smoked meats, breads, canned fish, or cheese. Finally, Group 4 — ‘Ultra Processed Foods’ — the category that has sparked much discussion recently, is characterised by extensive processing, numerous ingredients, and a lack of intact Group 1 foods. Examples in this group, according to Nova, include products like ice cream, pre-prepared frozen dishes, and chicken nuggets.

If you’re having trouble identifying Group 4 foods, they are not difficult to find. You have only to peruse your local grocery store’s snack aisles: fried snacks, crisps, candy, pastries — the category generally known as ‘junk food’.

It is important to note that the term ‘junk food’ carries negative connotations, and is also linked to a history of stigmatisation. Believed to be initially coined by Michael Jacobson, director of the American Center for Science in the Public Interest, in 1972, the term has been used to describe foods high in fat, sugar, or salt. That said, in a BBC article from 2006, author Brendan O’Neill delved into the inconsistencies in the categorisation of junk food — noting that the online search engine “Calorie King” implicated McDonald’s as the archetypal junk food outlet. Yet other, trendier, and more posh burger bars often serve fattier dishes and are not labelled junk food. Therefore, it is important to acknowledge that junk food, though culpable in diet-related diseases, is also used to stigmatise more affordable forms of food — while nutritionally similar products (but sold at higher-end establishments) are not stigmatised in the same way.

What does the research say about UPF and Health?

The Nova framework posits that the displacement of minimally processed foods (Group 1-2) by ultra-processed products (Group 4) is associated with unhealthy dietary patterns and associated implications, and Group 4 products have undoubtedly earned their negative reputation.

It is no secret that food industry giants have spent billions of dollars on producing designer foods — enticing us with formulations of salt, sugar, and saturated fat that we’re biologically disinclined to resist. And plenty of research has examined the associations between diets high in UPF with adverse health outcomes including:

- Cardiovascular Disease: A study (2021) spanning 18 years found that each additional daily serving of ultra-processed foods (per Nova) was associated with a 7% increase in the risk of developing Cardiovascular Disease (CVD). It is important to note that within this study not all UPF affected CVD in the same way. Specifically, bread, processed meat, salty snacks, and low-calorie soft drinks were linked to an increased risk of CVD. However, cereals were linked to reduced CVD risk. Some UPF showed no statistical significance either way.

- Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus (T2DM): A meta-analysis (2021) found that for every 10% increase in the consumption of Nova-designated UPF (in terms of calories per day), there was a 15% higher risk of Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus (T2DM).

- Obesity: A meta-analysis of 14 studies found an association between ultra-processed food intake and the prevalence of overweight and obesity. Most of these studies used the Nova classification to identify UPF, reinforcing the link between these foods (often high in fat and calories) and weight gain.

- Overconsumption: UPF are often designed for high palatability, which encourages overconsumption. A randomised control trial (2019) noted that individuals on an ultra-processed diet (per Nova) consumed, on average, 500 more calories per day than a less-processed diet. This overconsumption was associated with weight gain.

- Mental Health: A 2020 study in the U.S. indicated a positive association between Nova-designated UPF intake and depression. A more recent study (2023) observed an association between consumption of UPF and depression, as well as an increased prevalence of comorbidities like diabetes, hypertension, and dyslipidemia. However, within the UPF category, only artificially sweetened beverages and artificial sweeteners were significantly associated with depression. It is important to note that these associations are not necessarily causations. Unhealthy diets negatively impact mental health. But also, mental health contributes to unhealthy dietary choices.

- Micronutrient Deficiency: A 2023 study found UPF consumption is associated with increased odds of inadequate intake of micronutrients in childhood

Where does plant-based meat fit into the Nova system?

Despite current discussions categorising plant-based meats as UPF, seminal studies on UPF rarely included plant-based meats. Likely, this is because plant-based meats that exist today were not readily available/popular when Nova first emerged in 2009. However, a 2023 study determined that 37- 41% of plant-based products studied were ultra-processed as per the Nova criteria, though within the ultra-processed food group, nutrition content varied widely.

By strictly utilizing the Nova system and considering that plant-based meat is not a monolith, we can draw somewhat varied conclusions based on its categories. Detailed studies on the health impacts of plant-based meats will be covered later.

According to the Nova classification, meat substitutes like Beyond Meat Burgers, Quorn Meatless Grounds, and Impossible Foods Sausages may be considered ultra-processed foods (Group 4) due to their soy and pea protein isolates, and mycoprotein ingredients. Beyond Meat and Impossible Foods products also include methylcellulose, a synthetic form of cellulose, a standard food stabiliser, and an ingredient that lands firmly in Nova Group 4.

However, Nova also defines UPF as high in unhealthy saturated fats, sugars, and salt, but low in protein, fibre, and micronutrients, which makes the classification of plant-based meats complex.

For example, the Beyond Meat Burger contains 20 grams of protein per 113 gram patty, fulfilling 40% of daily requirements. Quorn is low in fat and high in fibre content and has equal protein bioavailability and zinc to conventional meat. Impossible Sausage is rich in essential micronutrients like Vitamin B12 and Zinc. Impossible products that contain the company’s heme ingredient, which have an equivalent iron bioavailability to conventional meat.

These intricacies suggest that while some ingredients fall under higher Nova classifications, the diverse nutritional profiles of the whole product challenge a simplistic categorisation of these foods as UPF. For example, a recent study found that when ultra-processed foods were separated into categories, some categories (such as breads and cereals) had positive impacts on health. While others, like high-sugar beverages and some meat products, had a negative impact on health.

What are the limitations of the Nova system?

The Nova system likely emerged in response to the challenges posed by multinational food corporations as they aggressively introduced Western-style processed foods and sugary drinks in developing nations.

“What we have is a war between two food systems, a traditional diet of real food once produced by the farmers around you and the producers of ultra-processed food designed to be over-consumed and which in some cases are addictive,” stated Carlos A. Monteiro, the founder of the Nova system.

It’s important to remember that its intent may not have been to provide an exhaustive guide for discerning healthy and unhealthy foods on a global scale. Therefore, there are several limitations to consider when using this system to assess healthy food choices:

1) Exclusion of alternative proteins

The Nova system, developed in 2009, predates the rise of modern plant-based meat, seafood, and dairy alternatives, possibly leading to misclassifications. That being said, even recent studies employing the Nova system, such as this one investigating the impact of UPF on depression, often omit alternative protein sources from their analyses.

2) Bias against novel ingredients

A noticeable bias against novel ingredients becomes apparent in the classification of specific components. For example, isolated starches such as cornstarch and potato starch, which have been extracted and used for centuries, fall into the processed ingredients category (group 2). In contrast, isolated proteins such as soy, pea, and whey protein, which have gained a more novel status with the development of more advanced protein isolation methods, are categorised as ultra-processed (group 4). Another example is vital wheat gluten, traditionally obtained by washing flour to remove starch. Despite its historical usage, modern automated processes have introduced confusion in its classification within the Nova system.

3) Lack of nuance and oversimplified categorisation

The primary consideration of the Nova system for establishing the link between nutrition and chronic diseases lies in the degree of food processing, prioritising this aspect over specific nutrients or food items. Consequently, the system may inaccurately categorise nutrient-dense foods as ultra-processed and lead to misconceptions that all commercially manufactured food lacks nutritional value. To illustrate this, diverse foods, such as baked beans, sugary sweets, plant-based yoghurt, and cheesy puff crisps, are classified as equally unhealthy UPF. In contrast, beer, cured meats, steak, and homemade chocolate cake avoid group 4 classification, neglecting nutritional variations within these items. As we discuss in further detail later on, a recent study revealed that specific subgroups within group 4 (such as breads and cereals) were actually linked to a decreased risk of developing cancer, heart disease and diabetes. Only sugary and sweetened drinks and processed meats demonstrated an association with increased risks, with no statistically significant differences observed in any of the other groups.

4) Varied interpretations and definitions

The literature indicates inconsistencies in applying Nova food categorisation to dietary intake surveys. Notably, some aspects of UPF definitions centre around formulation – specific ingredients like fats, sugars, salt, and ‘cosmetic’ additives, including flavours, colours, and emulsifiers – rather than the processing itself. Moreover, the inclusion or exclusion of specific food items categorised as UPF varies based on the research focus, leading to further ambiguities. Careful consideration and interpretation of results is therefore required when reviewing studies that employ the Nova classification system.

Indeed one study found only around 30% agreement on placement of foods within Nova categories among food experts, suggesting the food categorisations used across studies are almost certainly using different criteria for different food stuffs.

The terminology used can also be perplexing. For instance, in one paper for Public Health Nutrition, Monteiro asserts, “Processes enabling the manufacture of ultra-processed foods include the fractioning of whole foods into substances”. However, in another paper for World Nutrition, Monteiro and his team report that “Methods used in the culinary preparation of food in home or restaurant kitchens, including disposal of non-edible parts, fractioning, cooking, seasoning, and mixing various foods, are not taken into account by Nova.”

5) Demonisation of processing

Processing is a term that introduces ambiguity and encompasses various types of processes, from simple ones such as heating or chopping to more complex ones, such as extrusion and fermentation. The majority of the food that we purchase and consume has undergone some form of processing, and not all of these processes are inherently bad.

Processing can have a positive impact on the food industry for several reasons. For example, freezing is a popular method that not only extends the shelf life of food but also preserves its nutritional content. Dehydration is another process that helps to prolong shelf life while maintaining the food’s nutritional integrity. Canning is also used to eliminate harmful pathogens, thereby ensuring the safety and quality of the food.

By extending their shelf life and reducing waste, processing steps can also help to reduce the cost of healthier foods, such as frozen peas. This makes them a more affordable and convenient option compared to fresh peas, whilst maintaining their nutritional value.

The term ‘processed’ unfairly stigmatises some foods and ignores the vital role processing plays in ensuring food safety, accessibility, and sustainability.

6) Exclusion of other important factors that affect healthiness

The Nova system also fails to account for differences in the source or quality of ingredients and disregards the presence of potentially harmful compounds, such as the heterocyclic amines (HCAs) and polycyclic amines (PCAs) produced when processed and red meat is cooked at high temperatures. Additionally, the system overlooks the specific processes associated with the production of animal-based products, including aspects like feed composition and antibiotic usage.

Research papers that utilise the Nova system also fail to adequately address or highlight essential contributors to health outcomes within their abstracts, such as high caffeine and alcohol consumption. For example, whilst the following findings were discussed in a 2023 study, the association between alcohol and cancer risk is not mentioned in the abstract; you have to read the full paper and results and discussion sections to find it:

“Diets rich in processed foods tend to have an increased energy density, as well as a high contribution of alcoholic drinks, which might have partly explained the association between processed foods and cancer risk in this study. When alcoholic drinks were removed from the Nova classification, the associations between intake of processed food and rectal cancer, hepatocellular carcinoma, and postmenopausal breast cancer became non-significant, suggesting that drinking alcohol probably drove those associations.”

7) Lack of prioritisation of the nutritional profile of food

The Nova system does not offer a complete evaluation of a food’s nutritional worth, which may result in the omission of important health-related information, such as the exact nutrient levels or the existence of helpful and harmful components. This restriction emphasises the need for additional factors to be considered when trying to make well-informed and health-conscious food choices.

For additional context, it’s worth highlighting the British Nutrition Foundation’s position on ultra-processed foods, notably their conclusion: “At present, the British Nutrition Foundation believes that due to the lack of agreed definition, the need for better understanding of mechanisms involved and concern about its usefulness as a tool to identify healthier products, the concept of UPF does not warrant inclusion within policy (e.g. national dietary guidelines).”

What are the alternatives to the Nova system and what do they say about plant-based meats?

Several alternatives to the Nova system include the Nutri-score (developed in France originally and used widely throughout the European Union and the United Kingdom), Health Star Rating (Australia and New Zealand), the U.K.’s Nutrient Profile Model, and the Dutch Nutrient Database (NEVO). In each of the studies below, plant-based meat has been compared to conventional animal products.

Nutri-Score: Nutri-Score is a front-of-pack nutritional rating system widely used in the European Union and the United Kingdom. This system assigns a grade to food products based on their nutritional content. Negative points are awarded for nutrients that should be limited: calories, saturated fatty acids, sugars, and salt. Positive points are assigned for foods that should be encouraged, including high amounts of fruits, vegetables, nuts, healthier oils (like olive and nut oils), fibre, and proteins. The final Nutri-Score is displayed as a letter grade from ‘A’ (healthiest) to ‘E’ (least fit), often accompanied by a colour scale from green to red.

Courtesy of Markus Mainka, Canva

There are a few studies on plant-based meats within the Nutri-Score framework, with varied results:

- Processing not Primary Indicator of Nutri-Score for PBAPs: In one 2023 comparative study examining plant-based products and their animal analogues, levels of processing did not always align with nutrition scores for PBAPs. Plant-based products and minimally processed animal products generally received better Nutri-Scores than processed animal products, with 68% and 75% respectively earning A and B scores. However, while most of the PBAPs fell into Nutri-Score categories A and B (most healthy) they were also categorised as Nova 3 and 4 (processed and ultra-processed) of the Nova system, indicating that processing within this category does not necessarily equate to lack of nutrition.

- Higher Scores than Animal Meat: In another 2021 comparison study, a beef burger scored a D on the Nutri-score scale, while plant-based burgers scored a C (pea-based burger) and two Bs (soy burger/mycoprotein burger).

- Higher Fibre / Less Protein: In a 2022 comparative study results showed more products in categories A-C for plant-based meat analogues than conventional meat. However, Nutri-Score varied among products. Plant-based steaks were found to have more protein, less energy, fat, and salt, and better Nutri-Scores compared to other analogues. All meat analogues had more fibre than meat, though plant-based burgers and meatballs had less protein than their animal counterparts. Ready-sliced plant-based meats had less salt than cured meats. Generally, plant-based products contain more ingredients than animal meats.

Health Star Rating: The Health Star Rating is a front-of-pack labelling system used in Australia and New Zealand. This system evaluates the overall nutritional profile of packaged foods and assigns a rating ranging from ½ a star to 5 stars. It offers a quick, easy, standardised method for comparing similar packaged foods. The rating is based on the levels of saturated fat, sodium, sugars, and calories, with a higher star count indicating a healthier option.

- Higher Health Rating / Higher Sugar: A recent study (2023) showed that meat analogues had a higher health star rating and lower mean saturated fat and sodium content. Both animal-based and plant-based products had a generally low sugar content, but the latter contained slightly more total sugar. Meat analogues and meat products had a similar proportion of ultra-processed products (84% and 89%, respectively) based on the Nova system. 12.1% of meat analogues were fortified with iron, vitamin B12 and zinc.

The Nutrient Profile Model, United Kingdom: A regulatory tool developed by the Food Standards Agency, the Nutrient Profile Model serves as a tool to distinguish foods and drinks based on nutritional content. It aims to limit TV advertising of high-fat, salt, or sugar products to children.

- Better Nutrition Profile/High Salt: In a 2021 study of 207 PBM and 226 meat products, Plant-based meats had lower fat, saturated fat, protein, and higher fibre than meat, but most have significantly more salt. Based on the U.K.’s Nutrient Profiling Model, 14% of PBMs were classified as “less healthy” compared to 40% of meat products. About 20% of PBMs and 46% of meats were high in fat, saturated fat, or salt. Nearly three-quarters of PBMs tested didn’t meet UK salt targets, indicating a need for reduced salt content despite their generally better nutrient profile than meat equivalents.

Dutch Nutrient Database (NEVO): The Dutch National Food Composition Database (NEVO database) is a nutrition scoring system used for food and nutrition-related work in the Netherlands.

- Better/Varied Nutrition Profile: In a 2023 study, using NEVO guidelines, findings suggest that plant-based meat substitutes were often healthier than animal counterparts in terms of fibre, calories, saturated fat, and even vitamins like iron and B-12 (due to the Netherlands’ requirement of fortification).

Key Insights: Plant-based meats, overall, offer a better nutritional profile in terms of saturated fat and fibre content and receive higher nutrient ratings than animal products in frameworks like Nutri-score, Health Star, Nutrient Profile, and the Dutch Nutrient Database.

Nevertheless, they tend to be higher in salt and, despite their richness in protein (they still very much meet ‘high protein’ definitions from nutrition organisations), the protein per 100g tends to be lower compared to meat. Similarly, although they are low in sugar, plant-based meats typically contain more sugar than conventional meat. Additionally, they frequently include a greater number of ingredients, resulting in a more variable nutrient content.

The takeaway? Not all plant-based meats are created equal.

Despite the ‘Ultra-Processed’ Nova designation, widely-utilised nutrient guidelines from across the globe suggest plant-based meat can offer valuable and necessary nutrients, especially for those who are utilising them to avoid eating animal products.

What are plant-based meats and why do we need them?

Plant-based meats are food products that aim to emulate the entire experience of eating meat (taste, texture, appearance, nutritional value, etc.) whilst excluding many of the negative environmental and ethical impacts associated with animal agriculture such as high water use, deforestation, increased greenhouse gas emissions, religious dietary restrictions and poor animal welfare conditions among many others. Plant-based meat can be composed of various plant-based ingredients, including proteins, oils, and seasonings.

They are a promising solution to meet the rising demand for meat and provide a reliable source of nutrients sustainably. To quote GFI, “Plant-based meat allows consumers to enjoy the taste of meat at a fraction of the environmental cost.”

Some key benefits of plant-based meats include:

- Affordable nutrition

The escalating global population necessitates efficient and affordable sources of nutrition, especially in regions with limited access to diverse food groups due to factors like climate change. Climate change, along with contributors such as factory farming and soil degradation, is significantly reducing the amount of minerals (including calcium, iron, magnesium, and zinc), protein and B vitamins in crops. One paper even goes as far as stating that the negative impacts of these deficiencies are “existential threats”.

Despite being cost-effective, factory-farmed meat frequently lacks vital nutrients due to the animals being fed grain-based diets and the depletion of nutrients in the soil. The process of soil degradation, influenced by factors like intensive grazing, deforestation for livestock feed, and irrigation, further exacerbates nutrient deficiencies in both animal and crop-based products.

In contrast, the production of processed foods, including plant-based meat, offers a viable means of delivering essential nutrients in the face of environmental challenges. Additionally, it provides a more affordable option for those who may struggle to afford grass-fed beef or organic vegetables, for example.

- Reduced risk of zoonotic disease and antibiotic resistance

Antibiotic resistance poses a formidable threat to global health, with projections indicating that, by 2050, drug-resistant microbes could claim the lives of 10 million individuals annually, surpassing the current mortality rate of cancer. This alarming issue is exacerbated by the misuse of antibiotics, particularly evident in the animal agriculture industry. In the United States, an astonishing 70% of medically relevant antibiotics are utilised in animal agriculture to expedite growth and prevent diseases, leading to the development of antibiotic resistance.

This challenge extends beyond the U.S., as a comprehensive study by Manyi, Loh, et al. in 2018 highlighted irrational antibiotic use in clinical and agricultural settings (compounded by factors such as low socioeconomic status, inadequate sanitation and hygiene, and deficient surveillance systems), sounding alarms in developing countries. The study also emphasised the presence of antibiotics in animal-derived products and the emergence of multidrug resistance in environmental samples, posing a significant risk to public health.

In addition to antibiotic resistance, the proximity between humans and animals in traditional farming creates an environment conducive to the transmission of pathogens, leading to outbreaks of zoonotic diseases. Plant-based meats, produced without live animals, not only eliminate the use of antibiotics but also lower the risk of zoonotic diseases. Moreover, fewer crops are required to produce plant-based meats, which reduces the need for fungicides and subsequently mitigates the risk of antifungal resistance.

- Inclusive nutrition

Plant-based meats can offer several health benefits by addressing cholesterol concerns, as they are typically low in cholesterol or devoid of it, which contributes to cardiovascular well-being. In addition to reducing cholesterol, these alternatives provide a nutrient-rich option that contains essential elements like dietary fibre, which is essential for digestive health. This is especially important since approximately 95% of the US population and 40% of the UK population lack enough fibre. Processing methods can also improve bioavailability compared to unprocessed sources, which can be important for those who do not or can not consume animal products.

Moreover, plant-based meats offer a diverse range of vitamins and minerals, which help fulfil overall nutritional needs. Therefore, they are suitable for individuals who have specific dietary preferences or requirements, such as those who follow vegetarianism or veganism, or those who have restrictions on certain types of meat due to religious reasons. Plant-based meats provide an inclusive choice that respects diverse cultural and religious dietary preferences.

- Environmental impact

Whilst factory farming undeniably has a considerable environmental impact, there’s a common belief that grass-fed beef poses a lesser threat. However, the reality is that agricultural expansion, irrespective of farming practices, raises concerns for biodiversity, soil health, and forests.

With an existing population of 1 billion cows, the cumulative effect of grazing pastures and cultivating crops for animal feed results in livestock claiming 77% of global farming land, yet yielding only 18% of global calories and 37% of total protein – a remarkably inefficient system. In contrast, plant-based meat offers a more resource-efficient alternative, requiring 47% to 99% less land than conventional meat. Additionally, it significantly reduces greenhouse gas emissions by 30% to 90%, uses 72% to 99% less water, and causes 51% to 91% less aquatic nutrient pollution.

- Ethical impact

Traditional animal agriculture is associated with ethical concerns concerning poor animal welfare conditions. Animals may be subjected to crowded and stressful living conditions, routine use of antibiotics, and inhumane slaughtering practices. In contrast, plant-based meats offer a compassionate alternative by eliminating the need for live animals in the production process.

Are all plant-based meats UPF?

While in the mainstream media, only a handful of companies and brands are repeatedly featured, in reality, there are over 1,000 companies (see this comprehensive database) globally creating plant-based meat and animal alternatives. If we apply the Nova system classification to plant-based meats in a broad brush sense, a significant portion would be categorised as group 4 (ultra-processed). This is because several of these products incorporate ingredients classified as UPF, like pea protein isolate, and often undergo various processing techniques, including fractionation and texturisation. However, it’s important to remember that the Nova system, by design, may cast a broad negative light on processing, irrespective of the method used. In reality, leading research indicates that the processing steps involved in plant-based meat production play a beneficial role, such as denaturing antinutritional factors and enhancing protein quality and digestibility.

When directly comparing plant-based meat with other items typically profiled as UPF, its nutritional distinctiveness becomes apparent. Moreover, when analysing key studies that investigate the negative health impacts of UPF, plant-based meat is seldom featured. In fact, a recent multinational cohort study published in the Lancet, revealed that plant-based meats are not associated with a risk of multimorbidity and can actually reduce someone’s risk due to their high fibre content.

The Lancet study also found that the degree of processing within the Nova categories did not significantly alter the associated health risks for most ultra-processed products. Having said that, a battered plant-based nugget is undeniably less healthy than a plain and uncoated plant-based nugget. So not all processing methods can be considered equal either.

Whether all plant-based meats should be classified as UPF remains a nuanced question. It’s important to consider the health and nutrition credentials, as well as the level of processing of plant-based meat products, in an overall dietary philosophy.

What does the Nova system creator Dr. Carlos Monteiro say about plant-based meat?

Dr. Monteiro has referred to plant-based burgers as ultra-processed due to ingredients such as protein isolates. However, according to an article earlier this year in Wired, Dr. Monteiro admitted that ultra-processed foods are sometimes better than their unprocessed alternatives (plant-based burger vs. conventional burger), nevertheless, he still expressed concern that plant-based burgers might displace other, healthier plant-based foods.

While his is a fair concern, plant-based meats are intended to replicate the flavour, texture, and ingredients in meat-centric dishes and food preparations (sausage, burger, meatballs, dumplings), they are not intended to replace vegetables, legumes and beans.

How often should you eat plant-based meats?

There is currently no definite recommendation on how often one should consume plant-based meats in their diet, as there is only limited research available. However, early studies indicate that replacing traditional meat with plant-based alternatives can promote a healthy microbiome, help maintain a healthy weight, and reduce the risks of cancer and cardiovascular disease.

Moreover, further recent research indicates that plant-based alternatives pose no associated risk of multimorbidity when included in a balanced and diverse diet. The emphasis on moderation is significant, but the study also highlights the benefits of products rich in fibre, which plant-based meats offer.

A comparative perspective with established guidelines on red meat and processed meat intake offers insight: considering their negative health implications, the UK’s Department of Health and Social Care advises consuming less than 70g of red or processed meat daily. In contrast, the higher fibre content and nutrient bioavailability in plant-based meats can offer a convenient swap for people wanting to reduce intake to recommended levels.

What are the ingredients in plant-based meat that classify them as UPF?

When plant-based meat products are discussed in the media and popular culture, certain ingredients tend to be highlighted more than others. With 1,000 + products on the market, this list is not comprehensive; however, we’ve researched and included ingredients that have 1) incited the most concern and/or 2) are most common in plant-based meats. We have indicated which ingredients appear most frequently in plant-based meat.

So, our list may not be exhaustive, but we have researched and selected the most notable ingredients.

This list is intended to be a guide for decision-making, but check labels and research ingredients if you have further questions.

Methylcellulose

- Definition: A synthetic form of cellulose, used in food and cosmetics as a thickener, emulsifier, and fibre supplement.

- Use in Plant-Based Meat: Acts as a binding and gelling agent for a meat-like texture.

- Usage Frequency: Common

- Safety: FDA and EU approved as a food additive with tolerable intake listed as 5 mg/kg body weight/day, significantly higher than the current average consumption of 0.047 mg/kg body weight/day.

- Other Common Uses: Salad dressings, sauces, baked goods, frozen desserts.*

- Alternatives: Research is ongoing for non-synthetic alternatives like citrus fibre and duckweed.

*USDA Food Data Central is an online database that identifies brands and products that include certain ingredients.

Soy Protein Isolate

- Definition: A concentrated form of soy protein with 85% – 90% protein content, made by removing fats and carbohydrates from defatted soy flour.

- Use in Plant-Based Meat: Improves texture and contributes to gelling and thickening.

- Usage Frequency: Common

- Safety: Concerns for those with soy allergies. Contains phytates which might reduce mineral absorption — mainly a concern in diets overly dependent on soy. However, research shows that processing methods, such as extrusion (frequently used in plant-based meat production), can enhance protein digestibility in some legumes. While there are fears about soy’s phytoestrogens affecting hormone levels and cancer risks, current studies do not support these concerns.

- Other Common Uses: Protein powders and energy bars.

Pea Protein Isolate

- Definition: Pea protein isolate is a concentrated form of pea protein produced by milling dried peas into a fine powder and then solubilising (make soluble) the proteins. This mixture is then subjected to centrifugation to separate the soluble protein from insoluble components like fibres and starches. The resulting liquid is further processed to yield a high-protein powder.

- Use in Plant-Based Meat: Used in many plant-based meats due to high protein and nutrition content and low allergenicity.

- Usage Frequency: Common

- Safety: Research suggests that the protein is beneficial for muscle building, reducing blood fat levels, and lowering blood pressure. Contains phytates. As above, research shows that processing methods, such as extrusion (frequently used in plant-based meat production), can enhance protein digestibility in some legumes.

- Other Common Uses: Protein powders, protein bars, and cereals.

Textured Wheat Protein

- Definition: Produced by extruding wheat gluten; meat-like when hydrated.

- Use in Plant-Based Meat: Valued for water binding, texture, appearance, protein fortification, and insoluble fibre.

- Usage Frequency: Common

- Safety: Not suitable for individuals with coeliac disease or gluten intolerances.

- Other Common Uses: frozen meals, canned chilli and processed meats.

Guar Gum

- Definition: Guar gum is a natural substance obtained from the maceration of the seed of the guar plant.

- Use in Plant-Based Meat: It is widely used as a food additive for its water-absorbing and gel-forming properties, making it effective in thickening and binding food products.

- Usage Frequency: Common

- Safety: Recognised as safe by the FDA, its nutritional content varies by producer, but it’s typically low in calories, high in soluble fibre, and contains about 5–6% protein. Since it is mainly fibre; it can cause unwanted gastrointestinal side effects if over-consumed.

- Other Common Uses: Ice cream, cheese, and plant-based milks.

Locust Gum

- Definition: Locust bean gum is a natural substance derived from the seeds of the carob tree, a tree in the pea family. It is primarily composed of fibre-based carbohydrates.

- Use in Plant-Based Meat: It is used in foods as a stabiliser, thickener, and water binder. Found in many plant-based milks.

- Usage Frequency: Common in plant-based products, mostly in plant-based milks.

- Safety: Locust gum is a fibre source and a non-toxic food additive.

- Other Common Uses: dairy products.

Xanthan Gum

- Definition: Xanthan gum is made from the fermentation of Xanthomonas campestris, a type of bacteria, and is a water-soluble polysaccharide used extensively in food and pharmaceutical industries.

- Use in Plant-Based Meat: Due to its thickening and stabilising properties, it’s widely used in various products.

- Usage Frequency: Common

- Safety: Studies indicate even the highest doses of Xanthan gum don’t cause serious side effects. Some individuals feel abdominal discomfort when ingesting Xanthan gum, which is uncomfortable but not harmful.

- Other Common uses: Salad dressings, syrups and fruit juices.

Maltodextrin

- Definition: Maltodextrin is produced through a process of partially hydrolysing grain starches sourced from various plants, including corn, potato, wheat, rice, and sorghum. The process involves breaking down the compound with water.

- Use in Plant-Based Meats: Maltodextrin is commonly used as a thickener and to increase the shelf life of food products.

- Usage Frequency: Common

- Safety: Maltodextrin can cause spikes in blood sugar levels and may present health risks to those with diabetes. Additionally, some research indicates maltodextrin can alter gut biomes, and increase the risk of autoimmune diseases.

- Other Common Uses: salad dressing, mayonnaise and sports drinks.

Yeast Extract

- Definition: Yeast extract is a nutrient-rich substance derived from yeast cells, used to enhance food flavour. Yeast extracts can help induce the umami taste, the flavouring effect of monosodium glutamate (MSG), when providing glutamate at an amount below 1% in foods, i.e., below the amount required for pure MSG.

- Use in Plant-Based Meats: It is used in plant-based meats to add a more ‘meaty’ flavour.

- Usage Frequency: Common

- Safety: Yeast Extract is recognised as safe by most food safety bodies around the world. It is valued for its high vitamin and mineral content.

- Other Common Uses: Marmite (made of yeast extract), broth, soups, and seasonings.

Caramel Colouring

- Definition: Caramel colouring refers to a class of caramel colours that are globally regulated.

- Use in Plant-Based Meats: Caramel colour is generally utilised for colour, but it also may have other functions, such as flavour retention.

- Usage Frequency: Common

- Safety: Research suggests that no observable side effects have been identified for caramel colouring. Acceptable daily intake levels have been established to ensure safety, but some concerns persist due to production processes that sometimes use ammonia in processing, which may result in potential carcinogen exposure.

- Other Common Uses: soda, pastries and processed meats.

Coconut Oil

- Definition: Coconut oil is extracted from the meat of mature coconuts. It is commonly used in alternative proteins as a fat additive because it remains solid at room temperature, similar to animal meat.

- Use in plant-based meat: Coconut oil is ubiquitous in plant-based meat products. Projections estimate that the alternative protein industry may utilise up to 16% of the global supply of coconut oil by 2030. As the coconut industry is subject to market volatility, its supply chain may face instability. Additionally, coconut oil production has been linked to unsustainable environmental practices.

- Usage Frequency: Common

- Safety: Coconut oil is known to have a high saturated fat content. The American Heart Association has raised concerns over its impact on heart health.

- Other Common Uses: Nut butters, chocolate, cookies and snacks.

- Alternatives to Coconut Oil: There are many companies working on alternatives to coconut oil due to the unsustainability of coconut oil and palm oil (another common oil used in plant-based meats) supply chains.

Propylene Glycol

- Definition: Propylene glycol, a water-soluble and low-toxicity fluid, is FDA-approved for use in foods, drugs, and cosmetics.

- Use in Plant-Based Meats: It is used in food for its moisture-preserving properties.

- Safety: When used in high doses and over long periods, propylene glycol toxicity may occur.

- Usage Frequency: Uncommon

- Other Common Uses: Salad dressing, baking goods, and sauces.

Tertiary Butylhydroquinone (TBHQ)

- Definition: Tertiary Butylhydroquinone is a synthetic food preservative.

- Use in plant-based meats: Used to extend shelf life and improve safety by preventing the oxidation of fats.

- Safety: Though it is Generally Recognised as Safe (GRAS) by the FDA, there have been some studies showing that chronic exposure to TBHQ is associated with health risks. Therefore, the FDA has set limits on the permissible amount of TBHQ in food, restricting it to less than 0.02 per cent of the fat content.

- Usage Frequency: Uncommon

- Other Common Uses: Instant soup, salad dressing, and snacks.

Sodium Tripolyphosphate (STPP)

- Definition: Sodium Tripolyphosphate (STPP) is a synthetic ingredient used mainly in the food industry, particularly for seafood and meat processing.

- Use in Plant-Based Meats: It acts as a preservative and helps retain moisture and improve texture.

- Usage Frequency: Uncommon

- Safety: While STPP is approved by the FDA, some studies suggest that diets high in inorganic phosphates can undermine kidney health.

- Other Common Uses: Processed meats and fresh fish.

RED #3 (Erythrosine)

- Definition: Erythrosine is a red dye used as a colour additive in foods, cosmetics, and pharmaceuticals.

- Use in Plant-Based Meats: Used to add colour to certain products.

- Usage Frequency: Uncommon

- Safety: Erythrosine has notable health impacts — including thyroid disruption and has been found carcinogenic in animal studies. The state of California has recently banned it from all food products. The FDA is being pressured to do so on a national level. Use of the dye is strictly limited in the EU.

- Other Common Uses: sprinkles, cookies and ice cream.

Exception: Soy leghemoglobin – the following ingredient is exclusively found in Impossible Foods products as it is trademarked. However, there have been some concerns raised due to its processing and we want to address it.

- Definition: Leghemoglobin is a protein found in plants that carries heme, an iron-containing molecule (and what gives meat its ‘meaty’ flavour). Impossible Foods produces the ingredient using precision fermentation — a production process in which yeast is genetically modified with the gene for soy leghemoglobin. The yeast is grown via fermentation (in vats similar to beer) then the soy leghemoglobin (containing heme) is isolated from the yeast and added to Impossible Foods products.

- Safety: Studies indicate no adverse effects of Soy leghemoglobin, even in high concentrations. Additionally, soy leghemoglobin has been shown to have bioavailability equivalent to animal iron, implying it is a rich source of plant-based iron.

Note: Precision fermentation is more common than most people think. Not only is it used to produce synthetic insulin for Type 1 diabetic patients, it is highly likely that you have consumed a product made with precision fermentation if you have ever eaten dairy cheese. Around 80% of the cheese consumed worldwide is made using precision-fermented rennet. Rennet is an enzyme that is naturally found in the stomachs of ruminant animals, and it helps to separate milk solids from liquids for cheese production. Precision fermentation allows cheese to be made without extracting rennet from ruminant animal stomachs.

What does the research say about plant-based meats and health?

Plant-based meats have been decried as unhealthy due to their ultra-processed categorisation; still, available research suggests that consuming ultra-processed plant-based meat does not pose a risk of multimorbidity. In a recent study, among UPF subgroups, artificially or sugar-sweetened beverages, and animal-based ultra-processed foods posed the most notable risks, while plant-based animal alternatives and ultra-processed products such as breads and cereals were not. Additionally, the strongest available scientific evidence suggests that many of the processing methods used to produce plant-based meat can enhance its nutritional composition — such as increasing protein availability in legumes. However, it is important to acknowledge the variation in nutrition content among plant-based meat products (as in many food categories).

In this section, we will more closely examine the available research on plant-based meats and health. We will also dig into why the broad categorisation of all plant-based meats into the same group as candy and soft drinks is an oversimplification.

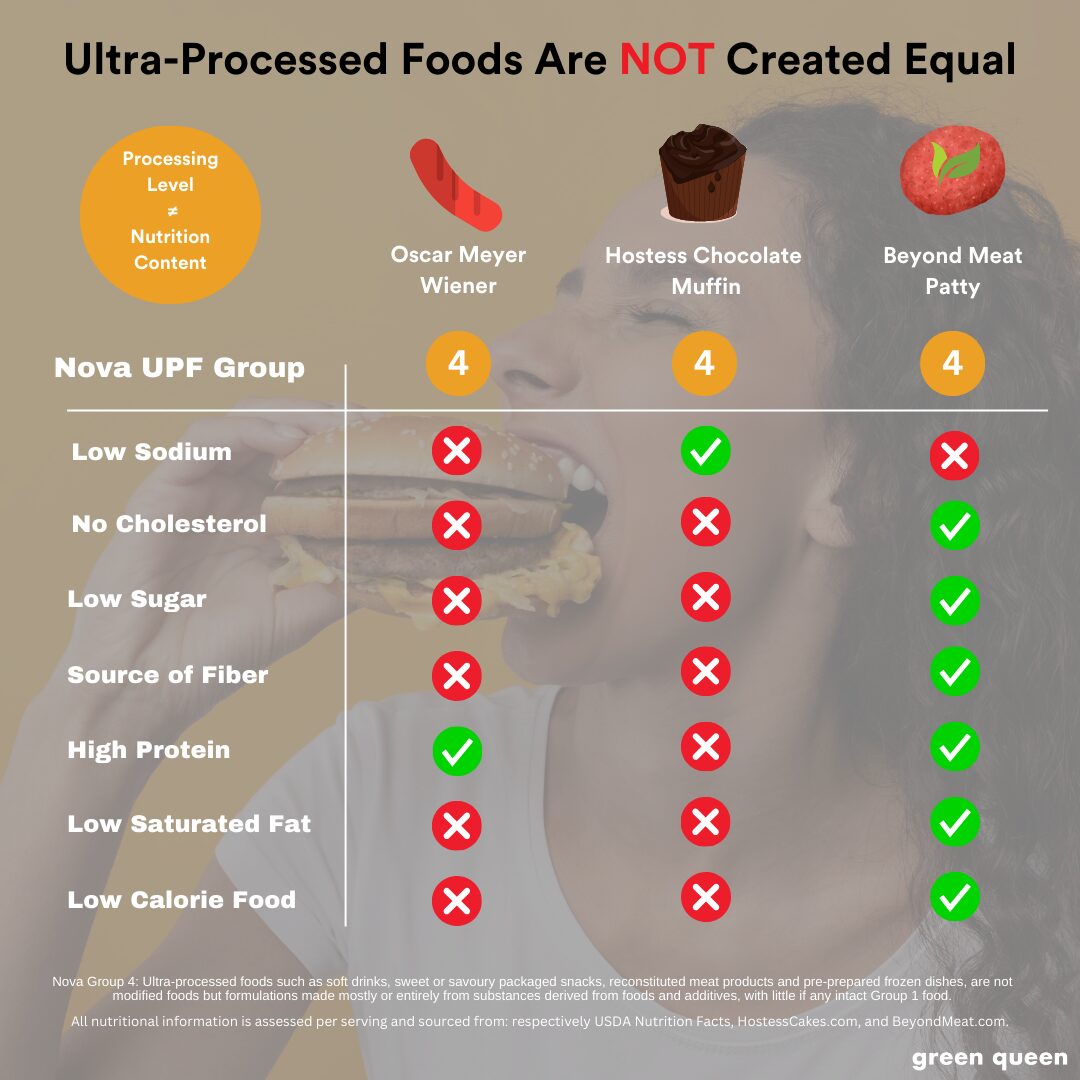

Simply put, not all plant-based meats or ultra-processed foods are created equal.

Here are five key takeaways:

1) Plant-based vs. animal meat

- Compared to the animal meat they’re replacing, plant-based products often come out on top nutritionally.

Omnivores and flexitarians often utilise plant-based meats to reduce animal meat consumption. Compared to meat, plant-based meat analogues have been shown to be significantly lower in saturated fat and cholesterol than their animal counterparts, and unlike animal products, are an excellent source of dietary fibre. Fibre is a dietary necessity severely lacking in global diets (95% of Americans are fibre deficient).

In a 2021 comparative study, 40% of meat products were classified as ‘less healthy’ compared to 14% of plant-based meat alternatives; similarly, 46% of meat products were considered high in total fat, saturated fat, or salt compared to just 20% of plant-based meat options.

In another study (2020), a randomised control trial found that replacing conventional meat with plant-based meat (Beyond Meat funded this study) was associated with a lower risk of heart disease.

While plant-based meat often comes out on top, variations within the plant-based and conventional meat categories require acknowledgement.

For example, in a 2023 study, 75% of unprocessed animal meat products achieved an A or B rating (most favourable scores) on the Nutri-Score scale. In comparison, 68% of plant-based meat alternatives received A or B scores, indicating a viable and comparative nutritional replacement to unprocessed animal meat. Only 43% of processed animal meats were rated as A or B, underscoring the nutritional drawbacks commonly associated with processed meat products.

In the same study, 17% of plant-based meats, 13% of unprocessed meats, and 35% of processed animal-based foods were in Nutri-Score categories D or E (least healthy).

- Consumers who choose plant-based meat reduce their intake of a product that potentially comes with environmental, health, and moral baggage.

People who choose to eat plant-based meat instead of animal meat may be motivated by other factors beyond nutrition. For example, when comparing a plant-based vs. factory-farmed beef burger — there are wide-reaching implications that extend beyond an ingredient list.

The widespread use of hormones in animal rearing, bacteria-infested feedlots, excessive antibiotic use, and human and animal rights abuses in Concentrated Animal Feeding Operations (CAFOs) raise serious concerns. These issues are compounded by the health risks linked to red meat, classified as a carcinogen and the potential health effects of residual antibiotics in commercially available beef. Moreover, the use of hormones in the US beef industry has significantly altered cow physiology.

2) Ingredients Matter: Some plant-based products are inherently less healthy than others; keep an eye on sodium content especially.

In a 2021 study, plant-based meat substitutes with ingredients like legumes (peas, soy) appeared more nutritionally adequate than other substitutes (such as plant-based cereal-focused products). Several studies, including a recent study published by Proveg International, have cited high sodium as having potential health impacts. In a 2021 study, ¾ of plant-based meat alternatives did not meet the United Kingdom’s national sodium standards. However, it still depends on the context. For example, if you’re replacing animal meat with plant-based meat, you might still be better off — as this study revealed that ready-sliced plant-based meat has lower sodium content than conventional cured meats. A recent study (2023) found that, generally, processed meats contained marginally more salt than plant-based alternatives. An exception was noted for meat salami, which was 1.8 times greater in mean salt content than plant-based meat alternatives.

3) Processing ≠ Nutrition

While levels of processing may be an easy way to distinguish foods from each other, digging into the nutritional content of food is key. It’s possible that Nova is better at categorising some foods as unhealthy than others.

For example, in a 2023 study on plant-based meat and dairy, most of the plant-based products categorised as ultra-processed (Nova 4) scored A and B on the Nutri-score scale (37.7% and 24%, respectively), indicating high nutritional quality.

However, among ultra-processed animal-based products, far fewer were categorised as nutritionally sound, with only 9.08% allocated to category A and 19.5% to category B on the Nutriscale.

Overall, this study showed that most plant-based meat aligned with Nutri-Score categories A, B (most healthy) and C (middle category). It is important to note that cheese alternatives were often in D or E Nutri-Score, which is aligned with other studies.

4) Plant-based meat is not a monolith

In multiple studies, nutrition in plant-based meat varied widely across the category. For example, in a comparison study (2021), one plant-based burger scored a C on the Nutri-score scale (pea-based burger) and two others scored B’s (soy burger/mycoprotein burger). In another study (2022), plant-based steaks showed significantly higher protein, lower energy, fats and salt contents, and better Nutri-Scores than the other analogues.

Some plant-based meats differ even among brands in terms of their health and/or nutrition. Both Beyond Meat’s Steak product and Impossible Foods Lean Beef Lite product have received American Heart Association Heart-Healthy Certifications.

At the end of the day, it’s important to remember that ‘plant-based’ refers to a broad category, not a uniform group, and preparation and nutrition content should be considered. Consuming large amounts of deep-fried foods is generally not recommended for health reasons, whether they are plant-based or animal-based – a deep-fried plant-based nugget is still a deep-fried nugget after all. That being said, consuming these foods in the context of a balanced and varied diet does not appear to pose any major risks.

It is about quality and quantity, not category.

5) And what about all those processed/chemical ingredients?

Ingredients like methylcellulose, soy protein isolate, and xanthan gum are common ingredients used in so many of the foods we eat every day (including breads, cereals, as well as in plant-based foods) to improve texture, increase protein content, and enhance mouthfeel — these ingredients, along with many others, are listed in the above section.

Most ingredients in plant-based meat are considered safe for consumption, even in larger quantities. However, some ingredients such as Propylene Glycol, Tertiary Butylhydroquinone (TBHQ), Sodium Tripolyphosphate (STPP), and Erythrosine have been linked to harmful side effects. We were interested in learning more about these ingredients due to their potential health implications. Despite being frequently mentioned by organisations like the Center For Consumer Freedom in warnings about plant-based meat, it’s important to note that very few plant-based products contain these ingredients.

For example, this poster titled ‘BLT? How about TBHQ-LT?’ infers that TBHQ is a common ingredient in plant-based foods. But on the Clean Food Facts website, only one product is listed to have TBHQ as an ingredient (Morningstar Farms Bacon).

Propylene Glycol is found in two products (both canned Loma Linda sausages) and STPP is in three products from Morningstar Farms. Erythrosine is found in four products, two of them the same Loma Linda sausages that contain propylene glycol. That said, maltodextrin, which has some health implications as listed in our ingredient research, is a fairly common ingredient in plant-based meats.

We have provided a comprehensive list of ingredients found in plant-based foods as well as their descriptions and research about their health impacts in the above Q&A.

6) An alternative to UPF? A case for ‘Ultra-Formulated’

UPF categorisation, despite its many interpretations, may be appealing due to its apparent simplicity — namely that a whole food = a ‘good’ food or that ‘food with many ingredients/ processed food = ‘bad’. However, as we’ve explored, the Nova system does not allow for much-needed nuance. Is there a better way?

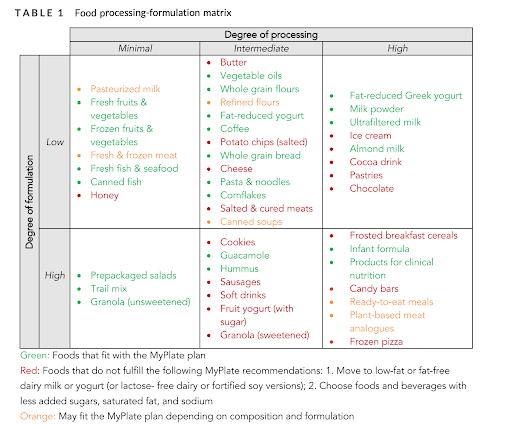

A recent 2022 study suggests that a food product’s “formulation” may better indicate its healthiness than its “processing.”

In the research, processing refers to the methods and techniques used to transform raw ingredients into food products. In contrast, formulation refers to the specific ingredients chosen and their proportions in a food product, including additives such as colouring agents, flavours, sugars, fats, and salt, which can lead to overconsumption.

The authors argue that the term “ultra-processing” places too much emphasis on processing rather than the product’s formulation. For example, infant formula (which lands in Nova 4) is considered safe and nutritious and can sustain babies when breast milk is unavailable. Additionally, they suggest that dismissing ultra‐processed foods because of their processing rather than their unhealthy formulation could undermine public acceptance of processing as essential for developing nutritious foods that are affordable, sustainable, safe from foodborne illness, and easily stored and transported.

In a comparison table, the authors explore a food processing-formulation matrix utilising the United States MyPlate guidelines, noting that foods that are considered healthy or unhealthy occur all over the matrix, whereby the prevalence of unhealthy foods increases with the degree of processing, and specifically, with the degree of formulation. The formulation, they argue, is often a conscientious choice to make foods more palatable and attractive and often includes the addition of sugar (or other caloric sweeteners such as high fructose corn syrup), saturated fats, and salt.

Image: Food Processing/Formulation Matrix, Levine and Ubbink, 2022

Regarding plant-based meats, the authors recognise concerns about some formulations containing high salt and saturated fats. Still, they acknowledge that there is no reason they cannot be formulated with acceptable amounts of salt, saturated fats, and high protein and fibre content to fit a healthy diet.

Are plant-based meats as healthy as dishes prepared with whole plant-based foods like lentils, beans, legumes, vegetables, nuts, and seeds?

Dishes freshly prepared from plant-based foods, such as lentils, beans, legumes, vegetables, nuts, and seeds, are generally among the healthiest foods you can eat. Research studies consistently highlight that a diet predominantly consisting of these foods leads to optimal health outcomes.

On the other hand, plant-based meats are formulated to replicate the taste and texture of animal meats. As a result, they complement whole plant foods very well and provide access to essential nutrients that we would normally get from meat, but more sustainably without the drawbacks of high levels of saturated fat, carcinogens, etc. They also include nutrients that can’t be obtained from animal meats or whole foods like beans, plants, and seeds. For example, plant-based meats are often a good source of fibre and can contain more bioavailable nutrients, including protein, omega-3, B12, iron, and zinc.

Plant-based meats are not intended to replace whole foods like beans, plants, and seeds. Instead, they aim to substitute animal-based foods, such as burgers, minced meat, sausages, and steak. They provide a transitional option for individuals shifting from meat consumption towards increased plant intake without necessitating significant dietary changes. Moreover, they offer essential nutrients that may be deficient in a plant-based diet.

In most cases, research suggests that replacing conventional meat with plant-based meat is a healthier option.

Therefore, while the consumption of dishes prepared with whole plant-based foods like lentils, beans, legumes, vegetables, nuts, and seeds is categorically healthier than plant-based meats, (most) plant-based meats can still be part of a healthy, balanced diet, especially when replacing animal products.

Are conventional meats UPF?

According to the Nova system, unprocessed meats like chicken breast or a steak would fall within the Nova 1 category. Processed meats are considered Nova 3 and 4 — Processed and Ultra-Processed Foods.

Regardless of Nova designation, consumption of animal products poses health risks.

Processed (Nova 3 & 4) meats, such as hot dogs (frankfurters), ham, sausages, corned beef, and biltong or beef jerky, are known carcinogens (cancer-causing), as designated by the World Health Organisation.

But when it comes to red meat*, UPF designation matters little. Whole, unprocessed (Nova 1) red meats are still listed as carcinogenic. When food is cooked at high temperatures or is in direct contact with a flame or hot surface, certain types of cancer-causing chemicals, such as polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and heterocyclic aromatic amines, are produced. This can happen during barbecuing or pan-frying.

*The WHO defines red meat as all mammalian muscle meat, including, beef, veal, pork, lamb, mutton, horse, and goat.

Are all UPF equally harmful to health?

Contrary to popular belief, the data points to a more nuanced reality. The recent Lancet study and earlier research (e.g. Chang, et al., Taneri, et al., Osté, et al.) indicate that specific categories of UPF, like meat products and soft drinks, are associated with health disadvantages, whilst other highly processed options, such as plant-based meat alternatives, do not share the same negative health correlations (see ‘What does the research say about plant-based meats and health?’ and ‘Are all plant-based meats UPF?’ for more info).

But it’s not just plant-based meats that get tarred with the UPF brush. Other UPF with favourable nutritional profiles include wholemeal bread, smoked tofu, wholegrain muesli, vegetable spreads, and nutrient-enriched soy and oat drinks, all of which could be considered healthy. On the other hand, less processed foods like honey, sugar, butter, and cheese warrant closer scrutiny, despite not being classified as UPF.

Why are UPF suddenly all over the news?

A recent book, ‘Ultra Processed People,’ by Dr. Chris Van Tulleken (April 2023), has brought UPF to the global stage over the past year — but this is certainly not their first appearance. Michael Pollan, a U.S. food thought leader, also wrote about ultra-processed foods in his 2008 book ‘In Defense of Food,’ referring to them, not as UPF, but as ‘edible, food-like substances.’ Dr. Monteiro cited Mr. Pollan as an inspiration for his 2009 work on the designation of ultra-processed food.

Additionally, a consumer research entity, the Center for Consumer Freedom (a dubiously-funded non-profit), has been conducting a campaign since 2019 to raise concerns about the ultra-processed nature and ingredients of plant-based meats.

In this next section, we provide an overview of Dr. Van Tulleken and Michael Pollan’s opinions on UPF and a deep dive into the Center for Consumer Freedom and its vendetta against plant-based meats.

What does Dr. Chris Van Tulleken say about plant-based meat?

Dr. Chris Van Tulleken has expressed scepticism about the health benefits of plant-based meat alternatives, especially those that are considered ultra-processed, stating in a Telegraph article in 2021: “I think there’s every reason to believe that in terms of health, an ultra-processed vegan fake meat product is probably worse than a minimally processed meat product.” He refers to these products as being at the “far end of the ultra-processed spectrum.”

Van Tulleken also comments on the ultra-processed vegan food market as a significant investment opportunity, but one that potentially encourages overeating. He explains that combining various ingredients such as pea protein into a single product disrupts natural nutritional signals, making it harder for the body to recognise when it’s full*.

In the same article, Van Tulleken emphasised that he wants to avoid dictating dietary choices but highlights that these foods are not necessarily healthy and questions whether they should even be considered food.

One thing worth noting here is that Van Tulleken spent his clinical career as an infectious diseases doctor, and is not a studied expert in diet or nutrition.

*While more research is needed, this 2022 research (funded by Australian plant-based meat company v2food) comparing beef mince and plant-based mince revealed that the plant-based mince had a higher level of satiation than meat. The plant-based mince included soy protein.

What does Michael Pollan say about plant-based meat?

Michael Pollan popularised the axiom, ‘Don’t eat anything your great-grandmother wouldn’t recognise as food,’ in his book, In Defense of Food. This phrase serves as a useful guide for consumers, yet it doesn’t account for the transformation of our food systems since the days of our great-grandparents.

Surprisingly, during a 2018 interview, Pollan praised Impossible Foods, labelling it an “excellent product.” This endorsement was unexpected, given his long-standing advocacy for whole foods and criticism of processed products, referring to them as “edible, food-like substances.” But Pollan’s openness to Impossible suggests a more nuanced view. In the article, he reflected on the broader issues tied to global industrial animal farming, including disease, environmental harm, and antibiotic resistance.

The author observes:

“Here was Pollan, openly acknowledging a shift in his food philosophy. He expressed admiration for something his grandmother wouldn’t have recognised as food, illustrating the complexity of Impossible Foods’ role in shaping the future of food. His once clear-cut seven-word mantra now entangled with the nuances of modern food technology and sustainability concerns.”

Pollan ultimately states: “By my definition, it’s not food. But that’s not to say I’m opposed to it.”

Why do I keep reading about how processed plant-based meats are bad/unhealthy?

If you feel like you’re suddenly being inundated by new information about the health risks of plant-based meats, you’re not alone. A recent study conducted by Ripple and commissioned by the non-profit organisation Changing Markets Foundation has examined an uptick in the spread of misinformation around plant-based meat.

The study showed that of the nearly 1 million scrutinised posts, 24% were about the unhealthiness of plant-based protein (including ‘ultra-processed), 31% criticised plant-based meats, while 18% focused on promoting the alleged health advantages of meat and dairy. Phrases like “no need to fear red meat” and “animal-based diets fulfil all nutritional requirements” were used to encourage meat consumption.

According to the analysis, around 425,226 accounts, both real and automated (bot), were involved in creating certain posts. But, out of these accounts, only 50,000 could generate all of the 3.6 million likes, shares, and comments. Interestingly, just 50 accounts, including famous right-wing politicians and commentators, were responsible for half of this activity.

It is important to note that misinformation about plant-based meats has been circulating for much longer than the duration of the Ripple study. At the heart of this misinformation campaign is one organisation known for its controversial campaigns, including pro-tobacco efforts: The Center for Organisational Research and Education, also known as the Center for Consumer Freedom.

Everything you need to know about the Center for Consumer Freedom misinformation campaigns

- Since 2019, the Center for Consumer Freedom (CCF) has led a campaign against plant-based meats. The organisation has placed full-page ads in The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal, and USA Today raising health concerns over plant-based meats, including comparing plant-based meat to dog food. In 2020, CCF produced a Super Bowl ad highlighting unfamiliar ingredients in these alternatives, such as methylcellulose. The ad suggested, ‘Fake bacon and burgers can contain dozens of chemical ingredients. If you can’t spell it or pronounce it, maybe you shouldn’t be eating it’ (as an aside, this attack prompted Impossible Foods to counter with an advertisement highlighting a study about faecal matter in meat, and the moniker — ‘poop, just because you can spell it, doesn’t mean you should be eating it’).

- The Head of CCF, Richard Berman, has long led controversial campaigns against groups such as labour unions and Mothers Against Drunk Driving (MADD). Originally funded by Big Tobacco to counter research linking smoking and cancer, Berman has spent his career protecting big industry. Current donors include meat industry advocates (per a CCF representative in 2019), but the donor list is not publicly available.

- While an organisation that has launched an attack on MADD may be dismissed as fringe, the language deployed in the CCF’s campaigns is intended to malign plant-based meat and unfortunately, it often finds a mirror in mainstream media — potentially due to the hundreds of thousands of dollars CCF pours into media and advertisement.

- Publicly available data indicates that in 2020 contributions and grants to CCF totaled 3,220,271. Interestingly, the organisation paid over 75% of those contributions ($2,444,724) to the for-profit Richard Berman and Company Inc. for ‘management, accounting, advertising, and research fees.’ The company also paid $220,068 to Fox for media and advertising, and Google Inc. $100,834 for media and advertisement.

- In 2019, contributions and grants totalled $2,984,369. $1,461,294 went to Richard Berman and Company Inc. $300,000 went to Primedia for Marketing, $181,979 to Google, for media and advertising and $173,284 to The New York Times for media and advertisement (perhaps for that full-page warning on plant-based meat).

- Publicly available IRS record forms 990 do not include lists of donors, but the origination in tobacco should give any discerning consumer pause. As animal meat is a known carcinogen (cancer-causing agent) according to the World Health Organisation, it appears that Berman has come full circle.

What does the research get wrong about plant-based meat and UPF?

The research on plant-based meats and UPF often overlooks critical nuances, leading to misinterpretations. Firstly, the majority of plant-based meat products were not around when a lot of UPF research based on the Nova concept was conducted. Since they’re not accounted for in earlier studies, plant-based meats may be unfairly associated with UPF due to the presence of specific additives.

Secondly, there are the limitations of the Nova system itself. The classification of plant-based meats lacks differentiation; there are over 1,000 alternative protein brands with varying nutritional profiles and processing levels, many of which are uniformly categorised as UPF.

The criticisms about the high-calorie density, low fibre content, and elevated levels of sugar, salt, and saturated fat in UPF do not apply to many plant-based meat products. In fact, these alternatives often demonstrate the opposite nutritional profile. Considering that 95% of the US population is fibre deficient, it seems counterintuitive to demonise a significant source of dietary fibre. Additionally, the cholesterol content, a concern with UPF, is low or absent in plant-based alternatives.

“Many of the specific reasons given why ultra-processed foods are unhealthy do not apply to plant-based meats!” says Dr Chris Bryant, Director of Bryant Research Ltd and research associate at Bath University, “While ultra-processed foods are criticised for their high-calorie density and low hunger satiety, evidence suggests that compared to meat from animals, plant-based meat has lower calorie density, and higher hunger satiety!”

Further, the research’s reliance on correlation in studies linking UPF to chronic diseases raises questions. Without direct evidence of biological mechanisms, correlation remains just that – correlation. To establish causation and confirm the potential health impacts of specific food groups, further research is needed.

In summary, the research fails to capture the distinct nutritional attributes and temporal evolution of plant-based meats, leading to incomplete and potentially misleading conclusions about their health impacts compared to UPF.

Are there other things we should consider when assessing the healthiness of our foods?

Understanding the quality and source of the ingredients is another important consideration when assessing the healthiness of food. For example, being aware of the composition of animal feed is essential, since it impacts the nutritional profile of meat, dairy, and other animal products. It’s also important to be aware of antibiotic usage in animal agriculture since its misuse can lead to antibiotic residues in food and water supply, contributing to antibiotic resistance (a global public health concern).

Products derived from wild animals can pose health issues too. Just like a roasted chicken or a grilled steak, a whole, unprocessed fish may fit neatly into the Nova 1 category as a ‘whole food’. However, fresh, wild-caught fish also comes with modern-day baggage; a recent study indicated a median of 60% of fish, belonging to 198 species captured in 24 countries, contain microplastics in their organs. This, along with the dangerous rise in mercury levels and a documented decline in the nutritional value of seafood due to climate change and overfishing, presents risks to human health.

Plant-based products can also contain harmful residues, such as pesticides. However, the risk of consumption can be minimised by choosing organically-grown ingredients. Organic products are often less harmful to soil health and can be a richer source of nutrients. Despite this, scientific evidence shows that consuming a significant amount of fruits and vegetables is beneficial to our health, irrespective of whether the produce is classified as organic or non-organic.

It’s worth noting that pesticide bioaccumulation, where levels increase further up the food chain, poses a more substantial risk when associated with meat consumption since livestock consume pesticides via animal feed.

Conclusion

The above guide covers a great deal of information, and it’s a lot to absorb in one go. In the interest of brevity, here are five key takeaways to keep in mind.

1/ The concept of ultra-processed foods (UPF) comes from a classification system called the Nova, which was created based on levels of processing, not nutrition.

2/ The vast majority of plant-based meat alternatives did not exist when the Nova system was created.

3/ Animal products are not required by law to divulge inputs or processing steps involved in ready-to-consume meat production – this is worth keeping in mind when comparing foods.

4/ All medical, food and nutrition research is in agreement: the healthiest diet is one that is majority plant-based from whole food sources such as vegetables, nuts, seeds, beans, legumes and fruits. Plant-based meat can be part of a healthy, balanced diet (as can a small amount of quality, minimally-processed animal foods) and according to the existing research, plant-based meats offer a range of health benefits.

5/ Plant-based meats are a broad category with many differences in terms of nutrition and ingredients used so evaluating them as a whole can lead to misleading and inaccurate conclusions.

No doubt, the topic of UPF and plant-based meat is a complex and layered one, and the ultimate goal of this guide is to provide context and nuance to the conversation. The aim here was to create a resource that was as comprehensive as possible with statements unhindered by agenda or ideology. We do hope it will prove useful to many.

About The Authors