5 Mins Read

People in the UK are less likely to be aware or worried about ultra-processed foods than their EU counterparts, and also consume more of these products, according to a pan-European survey.

Ultra-processed foods (UPFs) are everywhere right now – in grocery stores, in health studies, and in everyday conversations. There’s so much being written about them, it’s frankly overwhelming. Some are deriding these foods for being unhealthy, others say it’s not that simple. One thing you can say for certain is that we eat a lot of these foods, and people are more concerned about these than they were a couple of years ago.

In February, European research hub the EIT Food Consumer Observatory published results from a survey of nearly 10,000 consumers from 17 countries, which highlighted a lack of awareness around what constitutes a UPF, and the somewhat ill-perceived connection between UPFs and health – despite them taking up a majority of consumers’ diets.

In the UK, for example, UPFs make up 57% of an average person’s diet, and up to 80% when it comes to children or people with lower incomes. The country has the highest obesity rates among all major western European nations, but its population seem to be less aware or worried about UPFs, according to UK-specific data from the EIT Food survey obtained by the Grocer.

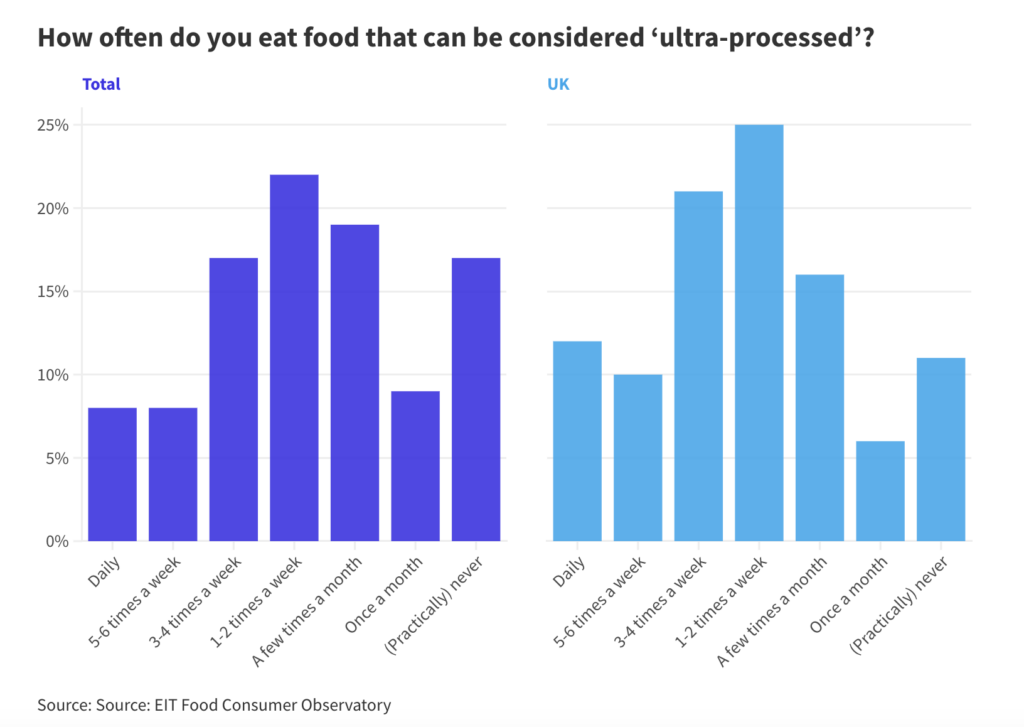

While 55% of Europeans consume UPFs at least once a week, this number rises to 68% for Brits. Moreover, 12% of consumers in the UK eat UPFs daily, versus 8% in the EU. Meanwhile, 61% of Brits think they are bad for their health, compared to 65% of Europeans.

Brits trust regulators, but labels create confusion

More UK consumers find UPFs cheaper (54% vs 49%) and more convenient (56% vs 41%) than whole foods, and only 48% of them go out of their way to buy unprocessed foods that require preparation (in contrast with 56% of Europeans). According to the British Nutrition Foundation, only a third of Brits who had heard about UPFs planned to cut their UPF intake in 2023.

This could be explained by their greater trust in health and regulatory bodies than their European counterparts. The EIT Food survey suggested that 43% of Brits think these departments have the necessary rules in place, but only 35% think so in the EU.

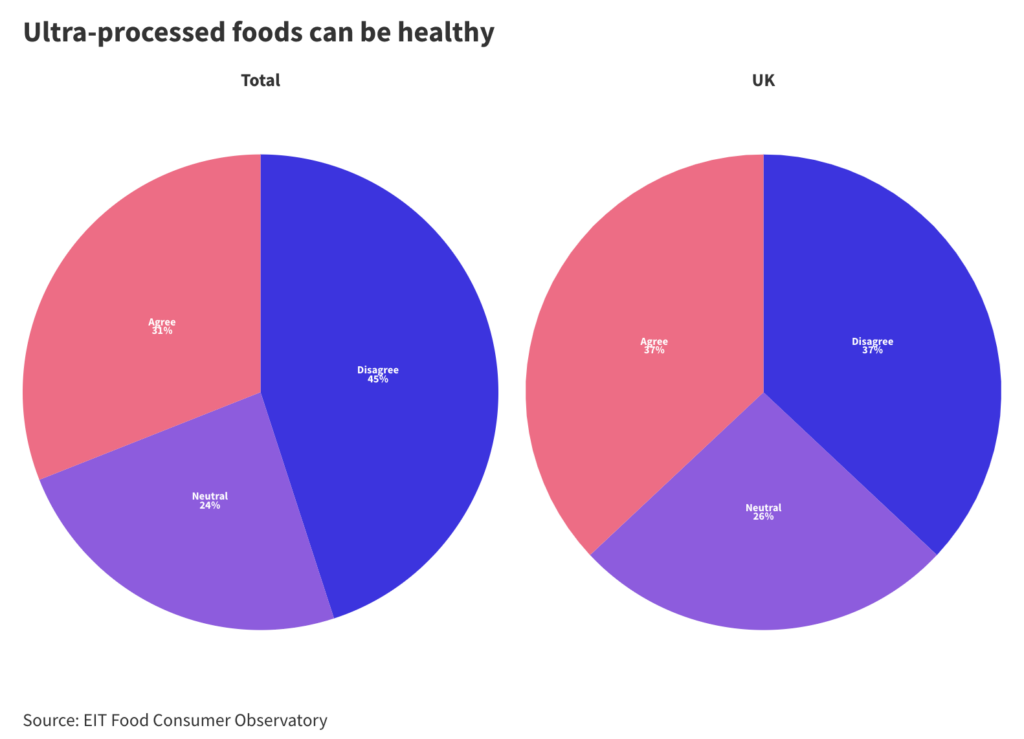

Likewise, 37% of Brits believe some UPFs can still be healthy, versus 31% in the overall survey. That is also the consensus of many food and nutrition experts, who have noted that the Nova classification that UPFs are built upon merely conveys the amount of processing a food has gone through, and this shouldn’t be correlated with nutrition itself.

“Breads and cereals often contain higher amounts of fibre, which, according to the Nova system, wouldn’t technically classify as UPFs,” food systems consultant Marlana Malerich told Green Queen last month. “It’s crucial to recognise the limitations of the Nova system, which does not account for nutritional content, leading to potential misclassification.”

Then there’s also the issue with packaging labels. To Malerich’s point, products that are designated as UPFs can still rank high on the Nutri-Score scale, or the traffic light system adopted in the UK. This breeds confusion, since the packaging tells you it’s healthy, but the UPF association makes it seem not so.

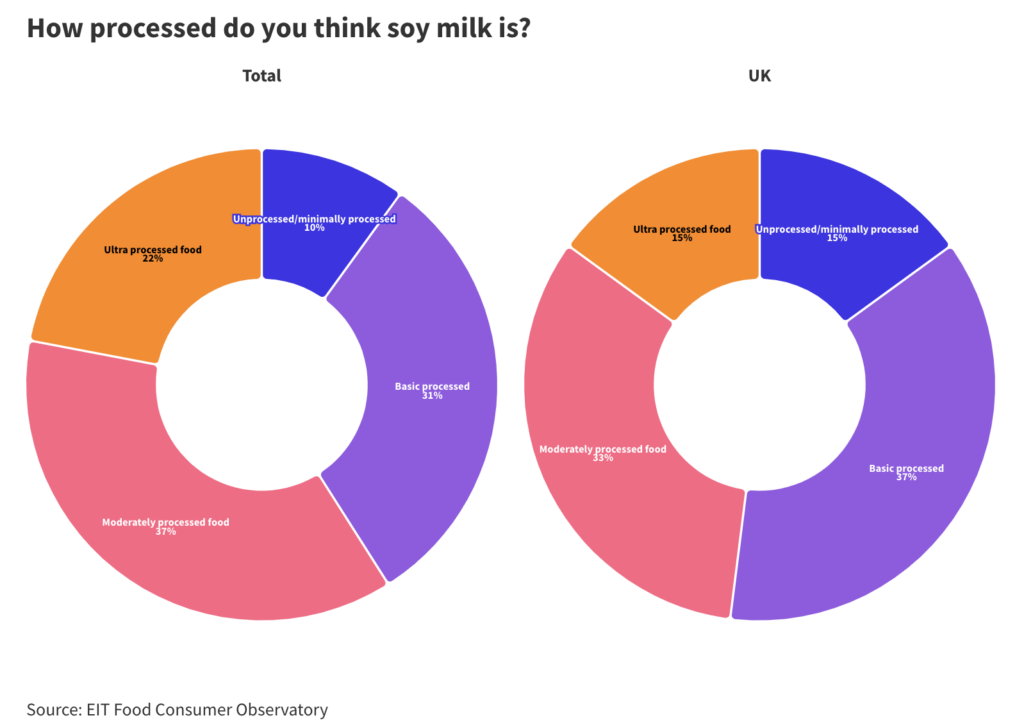

It’s probably why Brits are less likely to consider foods as UPFs, or even correctly identify how processed some foods are compared to their EU counterparts. For instance, fewer UK consumers think crisps are ultra-processed (31% vs 44% for Europeans), a trend that continues for soy milk (15% vs 22%), energy drinks (55% vs 61%), and raw, chopped chicken (7% vs 12%).

The vegan-UPF association

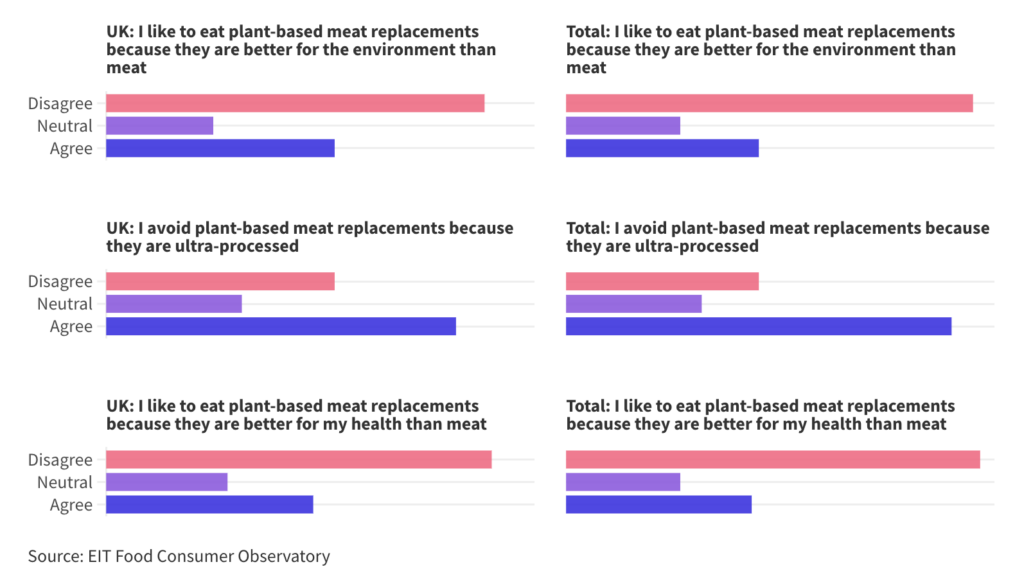

There is a large misconception around the health credentials of plant-based dairy and meat analogues, most of which fall under the UPF category but have nutritional benefits on par or better than animal-derived foods. The EIT Food survey showed that 54% of the respondents avoid plant-based meat products since they are UPFs, particularly those who don’t follow meat-free diets. In the UK, this drops to 49%.

Alarmingly, only 27% of Europeans think meat alternatives are better for the climate, and 57% feel they have a worse impact – despite meat accounting for twice as many emissions as plant-based foods. There is slightly greater awareness about the impact of animal agriculture in the UK, where 32% find them more environmentally friendly, and 53% think they are worse.

That, however, is still a very high percentage. And similar themes persist for the health aspect too, with Brits more likely to consider plant-based analogues better for their health (29%) than the total respondents (26%). But 54% of Brits and 58% of the overall respondents find them unhealthier than animal products. These attitudes are why many companies have shifted their marketing focus to promote the health benefits of vegan food, but these are likely impeded by government-backed campaigns like the one promoting meat and dairy in the UK.

Manufacturers are taking note of these changing attitudes by developing cleaner-label formulations, but these often cost a lot more than their processed alternatives. This was also a recommendation made by the EIT Food report, which suggested companies look into shorter, less “artificial-sounding” ingredient lists. Plant-based meat makers know that their link with UPFs is hindering them, and they too should explore additive-free labels without any transformation of ingredients (like protein isolates).

The study added that national food guidelines also must clarify whether plant-based alternatives are UPFs, and whether that matters for overall health. “Giving consumers clearer labelling, guidance and education could help them to better understand and engage with this issue, but it’s also important that concerns over processed food are considered in the wider context of people’s diets and wellbeing,” said Klaus Grunert, director of the EIT Food Consumer Observatory.

He added: “It’s also crucial that we continue to bolster our understanding and agreement of how we classify, evaluate and label foods, so that our advice to consumers is informed by the latest science.”