10 Mins Read

Alt-protein think tank the Good Food Institute (GFI) India has just released its first State of the Industry report for the country and by all accounts, there is much to be optimistic about. We break down the seven key highlights from the country’s smart protein sector.

India is making strong progress when it comes to the alt-protein sector – and this is crucial, given the South Asian country now has the largest population in the world, one which is predicted to continue growing over the next three decades.

It’s also the Asian country requiring the second-highest increase in alt-protein production, with 85% of its protein consumption needing to come from alternative and traditional plant sources (like beans, tofu, tempeh, etc.) if it is to carbonise.

So where does its ‘smart protein’ industry stand, and how far does it have to go? It’s these questions that GFI India addresses in its State of the Industry 2023 report – its first dedicated to the country. Here are seven key takeaways from the research, highlighting early adopters, government support, alt-protein regulation, labelling conventions, and more.

Plant-based dairy is king, but alt meat shows promise

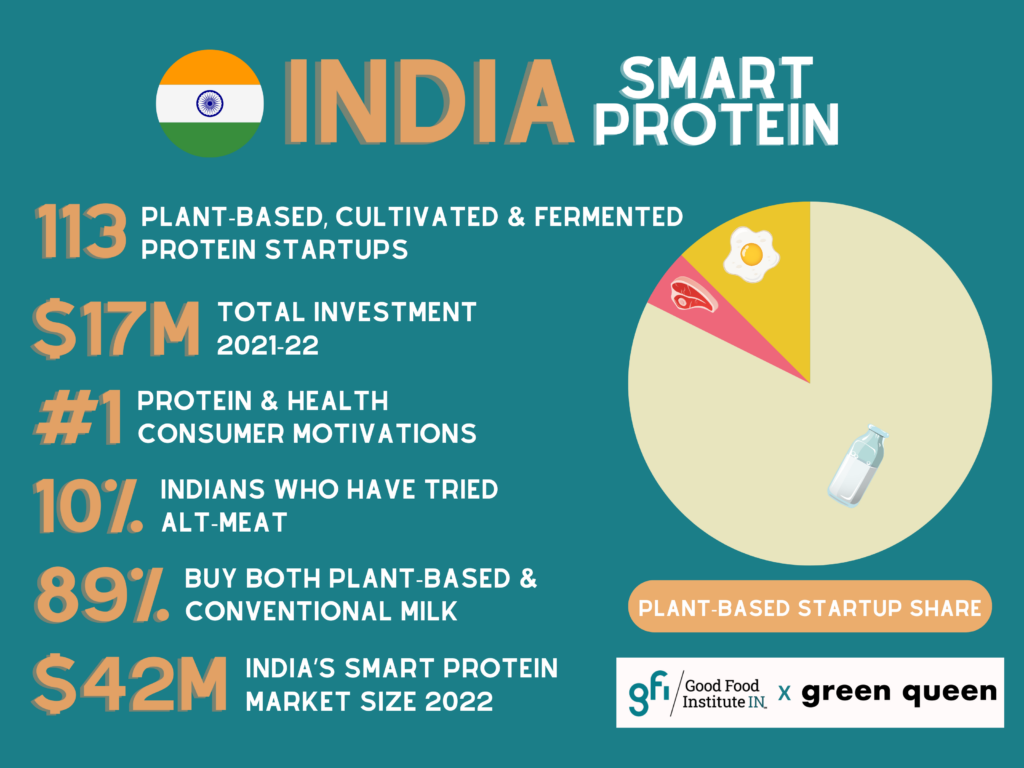

There are 113 companies working on plant-based, cultivated and fermentation-derived meat, dairy, seafood and eggs in India. Unsurprisingly – given the country has the largest dairy industry in the world – nearly two-thirds (65.8%) of plant-based businesses are focused on alt-dairy (with almond milk brands topping the list), and 30.1% on vegan eggs.

Meat alternatives only account for 4.1% of all vegan brands in India. There’s a large opportunity here, though, given that vegan chicken is the top product format across the sector (followed by alt-milk), and 77% of Indians consume meat daily, weekly or occasionally. Still, the current market landscape values plant-based dairy (₹250 crores/$30M) 2.5 times higher than meat alternatives (₹100 crores/$12M).

In terms of investment, alt-protein startups (across the three pillars) saw a modest investment of $17M between 2021-22, a small share of the $562M total that was injected into APAC companies in 2022. However, a survey of investors active in or entering the alt-protein sector by GFI showed that 99% of respondents are optimistic about the sector’s potential.

“I believe, with its world-class talent and proven track record of cost-efficient scale-up, India is uniquely positioned to be a smart protein innovation and manufacturing hub,” said Michal Klar, investor and funding partner at Better Bite Ventures. “This is especially relevant for technologies like precision fermentation that can benefit from talent and equipment currently used for biomedical research and production.”

Thanks to exports, India’s international presence is growing

While investment within India might not be too high, Indian alt-protein manufacturers are starting to make an international mark and contributing to the government’s $2T export goal by 2030.

Biotech firm Laurus Bio makes animal-origin-free growth factors, recombinant proteins, and cell-culture media supplements to cater to cultivated meat companies globally and help meet cost and scale requirements.

When it comes to plant-based, Greenest Foods shipped India’s first export consignment of plant-based meat from Gujarat to the US last year, while Wakao Foods shipped one of the largest-ever shipments (13 tons) of jackfruit-based products stateside earlier this year.

There were quite a few exports to Singapore, one of APAC’s alt-protein leaders. Blue Tribe Foods launched its line of burgers, tikkas and alt-meat products across Singapore supermarkets, while Shaka Harry will introduce plant-based meat products to the city-state’s Mustafa Centre. Evolved Foods, meanwhile, is exporting vegan meat alternatives to Singapore and Nepal.

More internationally, BVeg Foods supported Haldiram’s International’s launch of its Plant Perfect alt-protein range in the US, UK, EU and Australia, while shipping 22 tons of frozen vegan beef chunks to the UK in July. And as we reported last week, GoodDot – which has been exporting to Singapore, Canada, Nepal, the UAE, South Africa, Oman and Mauritius – entered the US market, with plans to move into the UK and Europe too.

Meanwhile, Kanpur-based Oatmlk became one of the first Indian plant-based dairy brands to export to the UAE and Singapore – which is significant as it isn’t based in one of the top three metro cities of New Delhi, Mumbai or Bengaluru. “New brands from tier-II and tier-III cities will play an important role in India’s export story in the coming decades,” says GFI India.

Bright visuals and ‘plant-based’ over ‘vegan’: how to nail product packaging

Since 2006, food and drink packaging in India has been labelled with green or red dots, signalling whether a product is vegetarian or non-vegetarian (which includes eggs in the country), respectively. But in 2021, the Food Safety Standards Authority of India (FSSAI) introduced a new vegan symbol to help consumers differentiate and identify plant-based products.

GFI India carried out a consumer study to identify packaging cues to help identify vegan food, finding that there’s a gap between comprehension and nomenclature – especially for plant-based dairy, which carries labelling restrictions. But there are certain things brands can still do to make their offerings easily identifiable.

Consumers prefer bright and bold colours with elements of green on the packaging, which they expect to be shaped intuitively (tubs for ice cream, blocks for cheese, etc.). Product imagery on the label is crucial in signalling the nature and taste of the food while mentioning the type of protein helps too. And similarly to global trends, most Indians prefer the term ‘plant-based’ over ‘vegan’.

Like many of their global counterparts, Indians value health above most other criteria when considering smart proteins. In 2021, a Kerry study found that health was the top motivating factor for Indians switching to plant-based food. This is especially true for alt-milk, according to GFI India’s research, with claims like “no added sugar” or “no preservatives” appreciated by consumers.

However, when it comes to meat, taste cues resonated more with consumers. But for both product categories, “high protein” was an important factor. Interestingly, claims about animal cruelty didn’t significantly motivate consumers to eschew animal-based food for vegan alternatives, which are primarily considered substitutes during religious events or festivals when meat consumption is prohibited.

Who is the Indian plant-based consumer, and what’s stopping the rest of the populace?

To identify the profile of the early adopters of vegan food in India, GFI looked at consumers who were likely to regularly purchase alt-meat, dairy and eggs, as well as pay more for these products.

The result? Young (aged 25-44), higher income (monthly household income of over ₹50,000/$600), well-educated (college graduates and above), living in urban areas, and flexitarians are the early adopters of plant-based foods in India. Vegan eggs and dairy count vegetarians and non-vegetarians as their target audiences too – and while people aged 18-24 are keen on alt-meat, they’re deterred by the price premium.

Of these early adopters, one in four say they’d consider giving up conventional meat, seafood, dairy or eggs in the future, citing issues like hygiene, smell, ease of cooking and heaviness on the stomach, as well as animal welfare and impact on the climate.

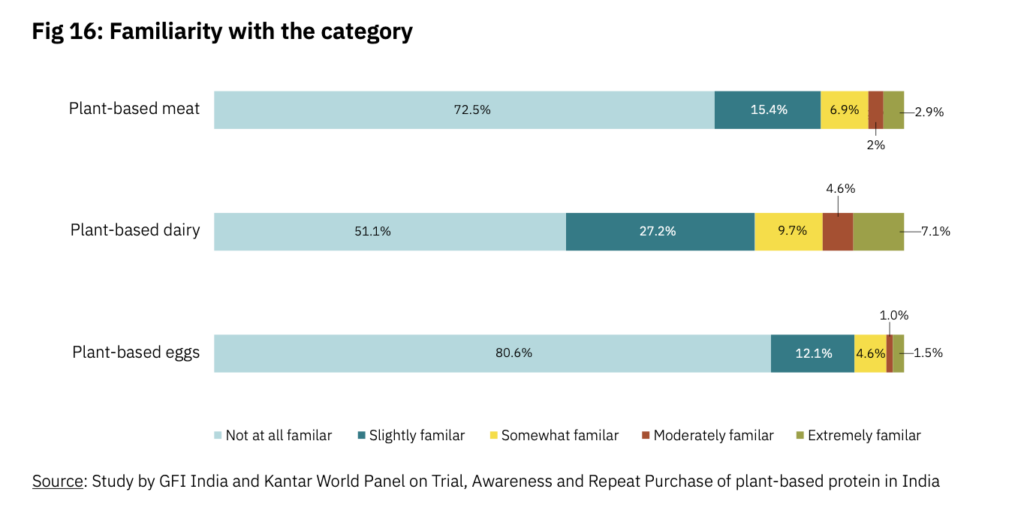

While half of these consumers are aware of plant-based milk, only 30% are familiar with alt-meat and 20% with vegan eggs. And of the households acquainted with these products, 23% have tried milk alternatives (with 43% intending to buy in the future), while only 10% have tried meat analogues (with 33% likely to purchase at some point). Meanwhile, 82% of Indians who have bought plant-based milk in the last six months say they’ll consider buying it again, with repeat purchases of alt-meat coming in at 72%.

Flexitarians are key here: 89% who have bought alt-milk buy conventional dairy as well, and 72% do the same for meat, with protein being a key reason for interest in both product categories (and health is equally important for milk).

Among the barriers to consumer adoption are resistance from family, a perceived ‘unnaturalness’, lack of clarity on health benefits, and taste and price. People over 45 feel these products are not relevant to them and possess a synthetic taste, while product availability is a key hurdle for many Indians.

There is increased government support for alt-protein in India

There are strong signs of administrative support and examples of public funding to help propel India’s smart protein sector to the next stage. Within India’s Ministry of Science and Technology, the Science and Engineering Research Board included cultivated meat research under its Competitive Research Grant Programmes and announced a funding call centred on making millet-based meat, egg and dairy proteins.

The Biotechnology Industry Research Assistance Council, meanwhile, has invested in multiple smart protein startups in India via initiatives like the Biotechnology Ignition Grant Scheme.

In March 2022, India’s minister of food processing industries confirmed that smart protein is eligible for financial assistance under the Pradhan Mantri Kisan Sampada Yojana, a central government scheme that provides monetary support to develop food processing and preservation infrastructure to set up food processing units.

A month earlier, a Ministry of Commerce department set up the Vegan Committee on Export Standards, Guidelines and Promotion for Vegan Food Products to aid the growth of the plant-based industry and set export guidelines. It’s part of the National Programme on Vegan Products, which aims to make India an export leader in the category.

As for state governments, Maharashtra (where Mumbai is located) included smart protein as a pillar to help each its $1T economy target by 2030. And its deputy chief minister signed a directive for manufacturing hubs that will focus on creating plant-based protein value chains.

“The potential for other state governments to chart a path for the smart protein sector is huge, especially since every state in India is uniquely positioned to benefit from various aspects of the innovation and production of smart protein food value chains,” reads the report.

No cultivated meat applications for regulatory approval yet

In India, the FSSAI is the body responsible for the regulatory framework of foods, including plant-based, cultivated and fermented proteins. The latter two fall under the Food Safety and Standards Regulations set out in 2017, which rule that if a product or ingredient doesn’t have a history of human consumption – or is obtained using new tech with engineering processes that significantly alter its composition – it’s classed as a non-specified or novel food product.

In 2020, the FSSAI formed the Working Group on Cultured Meat with regulatory and scientific experts to study the possible regulatory pathways for cultivated meat in India. So far, it hasn’t received any applications for the approval of cultivated meat or proteins made from biomass fermentation.

However, there has been progress on the precision fermentation front, with Californian pioneer Perfect Day obtaining premarket approval from the FSSAI for its animal-free whey protein after it purchased Sterling Biotech last year. Additionally, the regulatory body has approved the use of mycoprotein derived from Fusarium venenatum (the fungi strain used by Quorn).

There’s a lack of clarity when it comes to plant-based labelling in India

Like the EU, the FSSAI prohibits the use of terms like ‘milk’, ‘cheese’ and ‘yoghurt’ on the packaging of dairy alternatives. The regulator has specified that alt-dairy products can’t be considered as milk or milk products.

But in June last year, it finalised its Vegan Foods Regulations, a separate framework for plant-based food in India. Producers must comply with these rules and obtain approval to even label their products as vegan. And while the FSSAI published a list of FAQs for further clarity, it mentions that plant-based dairy and cheese analogues are not eligible for consideration as vegan food.

This makes things confusing for plant-based brands, as many alt-dairy products fall under the confines of the Vegan Foods Regulations and satisfy the definition of a dairy alternative. So it’s not clear whether these analogues can be classed as analogues, leaving companies in a neither-here-nor-there dilemma.

The FAQs also mention that the term ‘vegan’ can’t be clubbed with meat-related terms on product labels, with companies not allowed to make claims comparing alt-meats to their conventional counterparts in any sensory manner.

So while a lot of progress is being made, there are some key challenges for India’s alt-protein industry to overcome. “Building trust in these safe, sustainable, and scalable alternatives to conventional proteins is paramount,” Subhaprada Nishtala, director of ITCFSAN, the FSSAI’s training centre, told GFI India. “We envision a future where innovation, safety, and sustainability coexist harmoniously, enriching the dietary choices of the Indian public. Together, we can chart a path towards a more resilient and diversified protein ecosystem in India.”

Read the full State of the Industry 2023 report by GFI India here.