5 Mins Read

Singaporeans prefer the term ‘cultivated meat’ over related terms like ‘cultured’ or ‘cell-based’, according to a new study. Moreover, researchers found that people who consider cultivated meat ‘unnatural’ are – perhaps counterintuitively – more likely to acknowledge its benefits and consume it.

Singapore, which became the first country to approve the sale of cultivated meat in 2020, is a hotbed for this alt-protein sector. The new study, carried out by the Singapore Management University (SMU) and published in the Journal of Environmental Psychology, collected the thoughts of 10 meat-eaters who have tried cultivated meat, and 10 who haven’t.

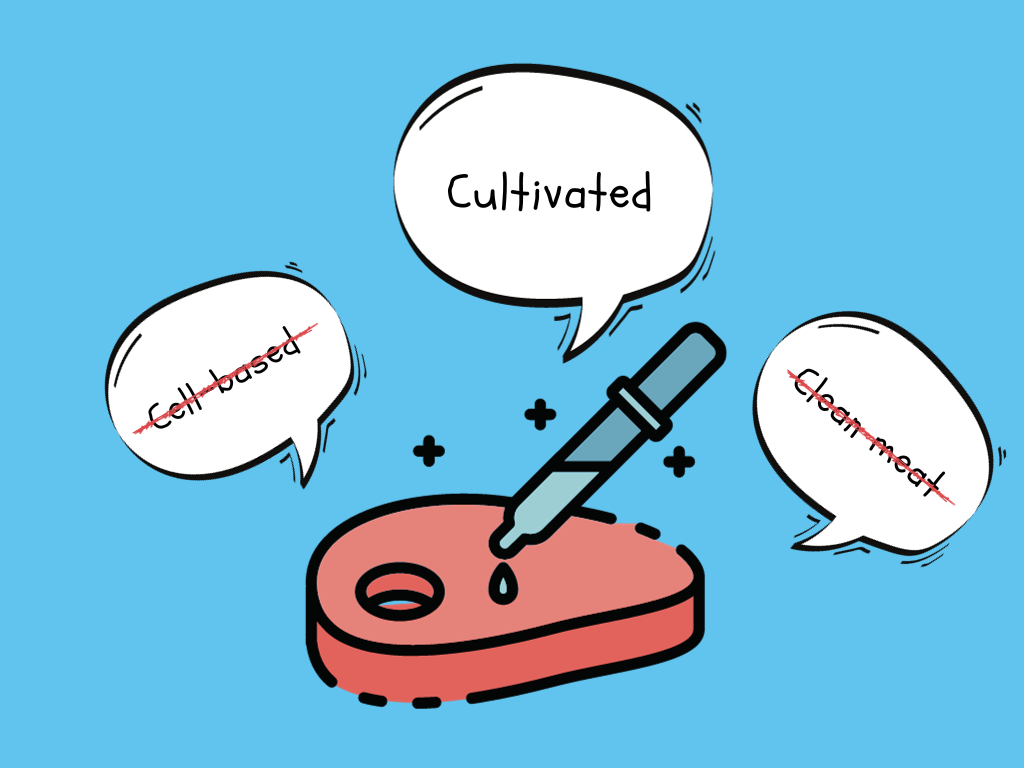

When asked what term they prefer to see it described as, ‘cultivated meat’ came out on top and was the term most strongly associated with positive attitudes towards these novel proteins. In order of preference, the other terms were ‘lab-grown’, ‘animal-free’, ‘cultured’ and ‘clean’ – the more literal ‘cell-based’ was the least favoured.

“That ‘cultivated meat’ was the preferred terminology is insightful,” said Professor Mark Chong, the study’s lead author. “Having a single, universally accepted term to describe this novel food technology not only helps to foster greater consumer understanding and acceptance but also reduces confusion about this new food source.”

What’s the best way to market cultivated meat?

The authors say consumer acceptance is the main barrier to cultivated meat, and among the many factors that impact it, nomenclature, framing (how it’s marketed), and perceived ‘naturalness’ are key. “Merely altering the names of dishes can affect consumers’ perception and increase the perceived authenticity of foreign dishes,” the study stated. “For example, the successful renaming of the un-appetizing sounding ‘Patagonian toothfish’ to ‘Chilean sea bass’ helped increase its acceptance among seafood diners around the world.”

The researchers presented five frames to understand what messaging would appeal most to Singaporeans: animal welfare, environmental benefits, health benefits, nutritional value and ‘food self-sufficiency. Interestingly, they found that no single frame was most effective in fostering consumer acceptance.

“Our findings suggest that as there was no significant difference in the influence of the five frames on overall consumer acceptance. Hence, cultivated meat companies and the Singapore food authorities can consider using each of the five frames interchangeably to promote cultivated meat in Singapore.,” said Chong.

The only exceptions to this were for the first two frames described above – associating cultivated meat with animal welfare (reducing slaughter) and environmental benefits (cutting emissions and warming) increased the acceptance of these foods among Buddhists.

“To foster consumer acceptance in Asian countries with significant Buddhist populations – such as Japan, Singapore, South Korea, and Thailand – cultivated meat companies may also want to use message frames focusing on how cultivated meat ‘reduces animal slaughter’ and ‘reduces global warming’,” explained Chong.

If it’s not natural, it’s better

The study sought to find if there were any dissimilarities in perceptions about how natural cultivated meat is among different age groups, but found “no consistent relationship between age, perceived naturalness, and the acceptance of cultivated meat”.

Perhaps most intriguing was the link between this perception of naturalness and consumer attitudes towards cultivated meat. The authors revealed that people who think cultured meat is not natural are more willing to consume it and see its benefits than those who think it is natural.

Professor Angela Leung, co-author of the study, said this aspect has received limited attention in cultivated meat literature: “Past research shows that discomfort with tampering with nature has been found to strongly predict perceived risk, and increase resistance to novel technologies. Therefore, our current research offers the first evidence to shed light on the link between aversion to tampering with nature and attitude towards cultivated meat.”

She added: “It is possible that the questions measuring aversion to tampering with nature may have led our study respondents to recognise that the production of cultivated meat could be an act to tamper with nature, but it is done to mitigate some undesirable elements of conventional meat. This may make them perceive that conventional meat production has its downsides, thereby promoting a more positive attitude towards cultivated meat.”

Leung acknowledged that more research is needed to examine this possibility. It’s worth noting that the sample size of this research was very small too – with a total of 20 respondents. Nevertheless, Leung argues the findings have a “practical implication” for cultivated meat marketing: “[Companies] can consider highlighting not just the benefits of cultivated meat, but also the undesirable elements of conventional meat in their messaging.”

Results consistent with previous research

This isn’t the first study to be conducted on consumer preference for cultivated meat nomenclature, but its results align with multiple analyses. In 2019, alt-protein think tank the Good Food Institute (GFI) and US cultivated meat leader Upside Foods found that ‘cultivated meat’ was the most preferred term among consumers, while responses to ‘cell-cultured’ were negative, and ‘cell-based’ and ‘cultured’ spawned mixed reactions.

In 2021, GFI president Bruce Friedrich wrote: “Since that work, quite a few companies have been using ‘cultivated meat’ as their primary nomenclature.” This prefaced another survey – this time of 44 industry CEOs, 75% of whom preferred the term ‘cultivated’. ‘Cultured’ came second at 20%, while only one executive favoured ‘cell-based’.

Additionally, research published in the Nature Portfolio journal last year found that – contrary to SMU’s analysis in Singapore – ‘lab-grown’ is be the least favourable term among consumers in the US (alongside ‘artificial meat’), while ‘cell-cultured’ and ‘cell-cultivated’ were the most popular. Moreover, within Asia-Pacific, industry stakeholders signed a memorandum of understanding declaring ‘cultivated’ as the preferred English-language term for these alternatives last year.

In 2021, Upside Foods strongly discouraged the use of terms like ‘lab-grown’ or ‘lab-based’, ‘synthetic’ and ‘fake’. It argued that ‘lab-grown’ is inaccurate and suggests cultivated meat will always be made in a lab – but once it scales up (as some have already), the products would be made in a food-production-like environment, similarly to thousands of products on grocery store shelves. “The labelling of cultivated meat and poultry products will be a crucial component of how our industry conveys the basic nature, essential characteristics, and value of these products to consumers,” the company said.