Labelling Lone Fruits As ‘Sad Singles’ Helps Cut Supermarket Food Waste, Shows Study

4 Mins Read

New research has found that associating lone fruits with ‘sad’ emotions can make supermarket shoppers feel sorry for them, increasing sales and mitigating food waste.

Have you ever felt so sorry for a single banana that you’ve ended up buying it?

I know I have – and apparently, I’m not alone. Research suggests that labelling loose bananas as “sad singles” moves grocery shoppers on an emotional level and increases the chances of it being bought, helping supermarkets reduce food waste.

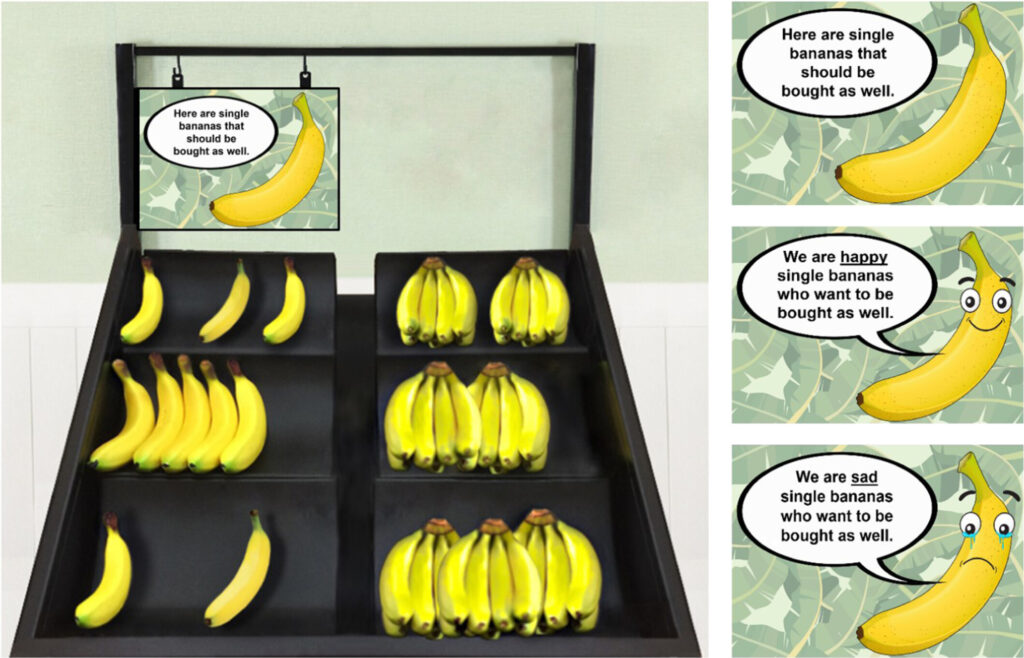

Academics from the University of Bath, RWTH Aachen and Goethe University Frankfurt sought to compare the efficacy of such labels with “happy singles” signage for loose bananas and tomatoes. Both sentiments were found to be more effective than a sign that showed no emotion – “Here are single bananas that want to be bought as well” – but the sad label turned out to be the most influential.

Sad bananas make for happier sales

The study, published in the Psychology & Marketing journal, observed the purchasing behaviours around single bananas – often separated as a result of shoppers tearing others from a bunch – of over 3,800 countries in the German supermarket chain Rewe. The retailer had previously labelled bananas as single and wanting to be bought, but minus the emotional element.

This in-store study was adapted as an online experiment, asking 745 consumers to imagine themselves in the situation. Shoppers were confronted with a sign showing a banana bearing a sad face under the message: “We are sad singles and want to be bought as well.”

The intervention increased the number of single bananas sold per hour by 58%, from 2.02 (when they were next to an emotionless sign) to 3.19. In contrast, the ‘happy banana’ signage drove up sales to 2.13 per hour (a 5.8% hike), proving that the more gloomy messaging was nearly 50% more effective on supermarket shoppers.

“As far as we know, this is the first study comparing happy and sad expressions on bananas separated from their bunch to look at the impact on sales,” said University of Bath’s Lisa Eckmann, a co-author of the study.

“The plight of the single bananas is really relatable and the findings have very practical applications for boosting sales and reducing food waste from our supermarkets,” she added.

A further online study revolving around tomatoes produced similar results, while the researchers also investigated the impact of price discounts on bananas. They found that the ‘sad banana’ effect didn’t outperform a drop in price – lowering the cost was more effective at driving people to buy them.

But when retailers can’t or don’t wish to reduce the price of such produce, using such sad anthropomorphism can be an effective strategy to boost sales of single fruits and vegetables, as well as cut down on food waste.

Study highlights retail opportunity to slash food waste

The number of bananas that go to waste every year is staggering. In the UK, 30% of consumers throw away the fruit even if it has a minor bruise or black spot, while 13% do so if there are any signs of green. This amounts to 1.4 million perfectly edible bananas ending up in the bin annually, according to one estimate, resulting in losses of £80M. Across the Atlantic, Americans get rid of five billion bananas each year.

The study notes how single bananas account for the highest amount of climate impact and food wasted on the retail level, with current avoidance practices explicitly listing single bananas as a preventable source of food waste.

“I wasn’t aware of how single bananas accumulate to such a big food waste problem, and now I always look out for loose, single bananas when I’m shopping,” said Eckmann. “The need to belong is one of the most basic human motivations, and applying sadness to single, stray bananas evokes a compassionate response from shoppers. Labelling bananas with sad facial expressions sounds cute, but there’s very much a serious purpose.”

The study proves that this is an easy, low-cost, effective intervention for retailers and policymakers, she explained. Retailers, for example, can apply a step-wise intervention approach where they first use emotional labels as a sales-boosting strategy, before turning to price discounts if necessary.

“We don’t know whether consumers might get emotionally numb to sad bananas in the long term, but it’s an idea that certainly draws people in, and is easy to act on,” Eckmann said. It opens up the potential for future research to examine which conditions sad expressions are more effective than happy ones in – for example, when produce is deformed or slightly damaged.

The study comes amid retailers’ efforts to reduce food waste, which accounts for up to a tenth of global emissions. In the UK, supermarkets and food organisations are calling for mandatory food waste disclosure in the sector, and have set up a redistribution project to tackle hunger, just as industry bodies begin work on a food waste reduction plan.

Walmart is working with organics recycler Denali to limit the amount of expired food going to landfills in the US, where the Biden-Harris administration unveiled the first national food waste strategy over the summer.

Discount retailer Lidl, meanwhile, has teamed up with the WWF on a 31-country project to conserve biodiversity, promote planet-friendly diets, and reduce food waste.