Climate Change is Raising Arsenic Levels in Rice, Putting Billions at Risk

6 Mins Read

Researchers have found that rising emissions and temperatures are linked to increased arsenic levels in rice, putting billions at greater risk of cancer and other diseases.

Climate change is making the world’s most consumed grain more toxic, raising fears about the potential health risks of a dietary staple in Asia, researchers have found in a concerning study.

Half the world depends on rice for most of its food requirements, and 95% of the grain is produced and consumed in developing countries. These populations already bear the brunt of climate change, and now face further threats through their diets.

Scientists in the US and China have uncovered that high temperatures coupled with increased carbon levels in the atmosphere – both a result of rising greenhouse gas emissions – could significantly impact arsenic concentrations in rice.

The presence of arsenic in rice has been a long-known issue. The naturally occurring chemical can build up in the soil of paddy fields and be absorbed by the grains of rice. Exposure to small amounts of inorganic arsenic (a form that doesn’t contain carbon) through food or water consumption can cause cancers, heart disease, diabetes, as well as neurological problems in infants.

The amount of arsenic found in rice can vary greatly and has led researchers to find ways to reduce its levels. “Previous work has focused on individual responses – some on CO2 and some on temperature, but not both, and not on a wide range of rice genetics,” said Lewis Ziska, an associate environmental professor at Columbia University.

“We knew that temperature by itself could increase levels, and carbon dioxide by a little bit. But when we put both of them together, then wow, that was really something we were not expecting,” he noted. “You’re looking at a crop staple that’s consumed by a billion people every day, and any effect on toxicity is going to have a pretty damn large effect.”

How climate change will make rice more toxic

Over a 10-year period, the researchers grew 28 strains of rice in four different locations in China, measuring the impact of rising greenhouse gas emissions on the crops. As both carbon emissions and temperatures increased, in line with global climate projections, the amount of arsenic grew in 90% of the rice.

This is because of changes in soil chemistry that favour arsenic, which can then be more easily absorbed into rice grains. The problem is related to irrigated paddy fields, where 75% of rice is grown. While rice can be swamped by weeds and other crops, it grows well in water.

Farmers flood the fields after planting the seedlings, though this too poses a problem: it leaves no oxygen in the soil. This leads anaerobic bacteria to arsenic to accept electrons as they breathe, thus reacting with other minerals in the soil that make the arsenic more bioavailable.

This changes the microbiome of the soil, with a massive influx of arsenic-friendly bacteria. This is what would get worse with temperature and CO2 concentration rises. As the bacteria in the soil receives more carbon and gets warmer, it becomes more active.

Inorganic arsenic – more toxic to humans because it’s less stable – has been classified as a “confirmed carcinogen” by the World Health Organization. “From a health perspective, the toxicological effects of chronic inorganic arsenic exposure are well established, and include cancers of the lung, bladder, and skin, as well as ischemic heart disease,” said Ziska.

“Emerging evidence also suggests that arsenic exposure may be linked to diabetes, adverse pregnancy outcomes, neurodevelopmental issues, and immune system effects.”

According to the US Environmental Protection Agency, consuming 0.13 micrograms of inorganic arsenic per kg of body weight would raise the risk of bladder cancer by 3% and diabetes by 1%. While these may feel small, when you consider countries with high per-capita rice consumption, it adds up.

Researchers call on regulators to step up

As part of the study – published in The Lancet Planetary Health journal – Ziska and his colleagues projected the increases in disease risk in the world’s seven largest rice consumers, all based in Asia. In each of the countries, there was a sharp rise of ill health effects by 2050.

In China, the number of cancers linked to rice-based arsenic exposure could reach between 13.4 and 19.3 million by mid-century. These projections are based on a worst-case scenario where global temperatures reac 2°C above preindustrial levels – 94% of scientists from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change say the world will cross this threshold by the end of the century.

The study did have some limitations. It assumed that people will keep eating the same amount of rice in 2050 as they do now, even though consumption tends to drop with rising incomes. On the flip side, it took into account that white rice would still be as dominant as it is today. A shift towards higher brown rice intake could actually be worse, since white rice – despite being less nutritious – contains less inorganic arsenic than brown rice.

“Our study underscores the urgent need for action to reduce arsenic exposure in rice, especially as climate change continues to affect global food security,” said Ziska.

Policy interventions have been few and far between, with the study calling such measures “largely voluntary, inadequately comprehensive, or unenforced”. For example, the US Food and Drug Administration recommends a non-regulatory action level of 0.1 micrograms of inorganic arsenic in infant rice cereal, but doesn’t formally regulate the chemical’s presence in any food.

The EU, meanwhile, has set enforceable limits of 0.2-0.3 micrograms per kg for rice and other products containing the grain, while China has proposed a similar limit. Under the elevated temperatures and CO2 concentrations projected in the study, more than half of the rice sampled would exceed these limits.

“We believe there are several actions that could help reduce arsenic exposure in the future,” said Ziska. “These include efforts in plant breeding to minimise arsenic uptake, improved soil management in rice paddies, and better processing practices. Such measures, along with public health initiatives focused on consumer education and exposure monitoring, could play a critical role in mitigating the health impacts of climate change on rice consumption.”

The startups trying to save rice and the planet

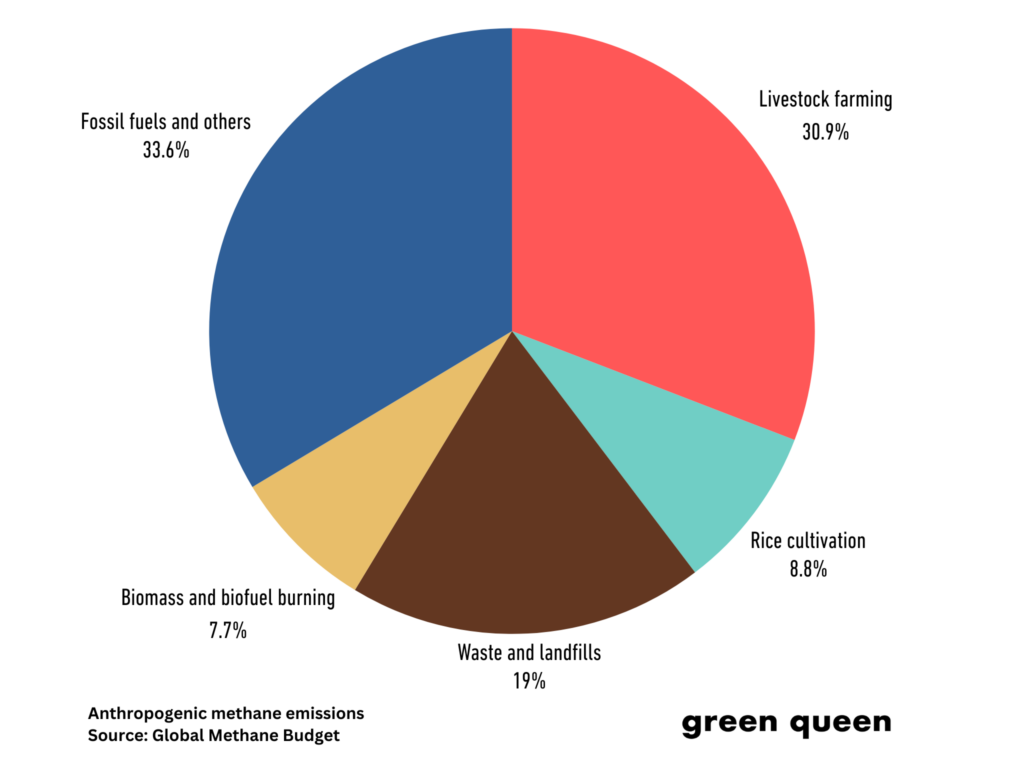

Climate change and rice have a reciprocal relationship. Rice cultivation is responsible for 9% of anthropogenic methane emissions and accounts for around 1.5% of global greenhouse gas emissions. For context, the entire aviation industry makes up 2% of the latter total.

However, increasing temperatures could shrink rice yields by 40% by the end of the century. In China, extreme rainfall has reduced rice yields over the last 20 years. And in Vietnam, where rice generates more emissions than the entire transportation sector, almost 250,000 acres of land in the Mekong Delta – its rice bowl – is being taken out of production, partly due to climate change.

This has led several startups to try and tackle the impact of rice on the planet, and vice versa. This includes Indian-American firm MittiLabs and France’s CarbonFarm, both of which use AI and satellite tech for carbon credits, though the efficacy of the voluntary carbon market has been called into question multiple times.

In Singapore, Rize buys seeds, fertilisers, and other inputs in bulk and sells them to farmers who implement alternate wetting and drying. This practice, which could lead to a 55% reduction in methane emissions in combination with other technologies, is also promoted by another Southeast Asian startup, AgriG8, whose gamified digital platform helps rice farmers lower emissions.