Plantasia Author Pamelia Chia: ‘Vegetables are Dynamic and Exciting – Them Being Vegan is Beside the Point’

13 Mins Read

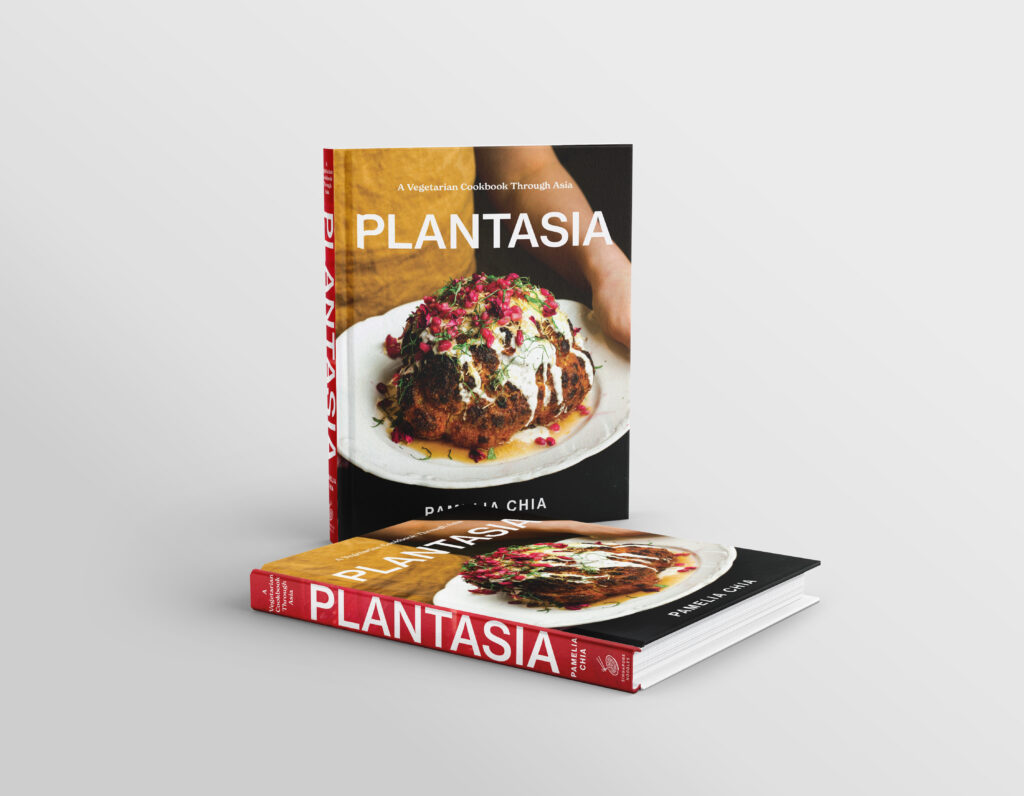

As she gears up to release her second cookbook, Plantasia, Singapore-born chef and food writer Pamelia Chia tells Green Queen about why she hates the term ‘meat substitute’, why vegetables rule, and the three things you should always have in your pantry.

Meat was part and parcel of Pamelia Chia’s identity as a child. Growing up in Singapore – where vegetarian cooks are often stigmatised or judged – she knew her way around the nooks and crannies of a fish head or a pig trotter. And it’s something she felt very proud of.

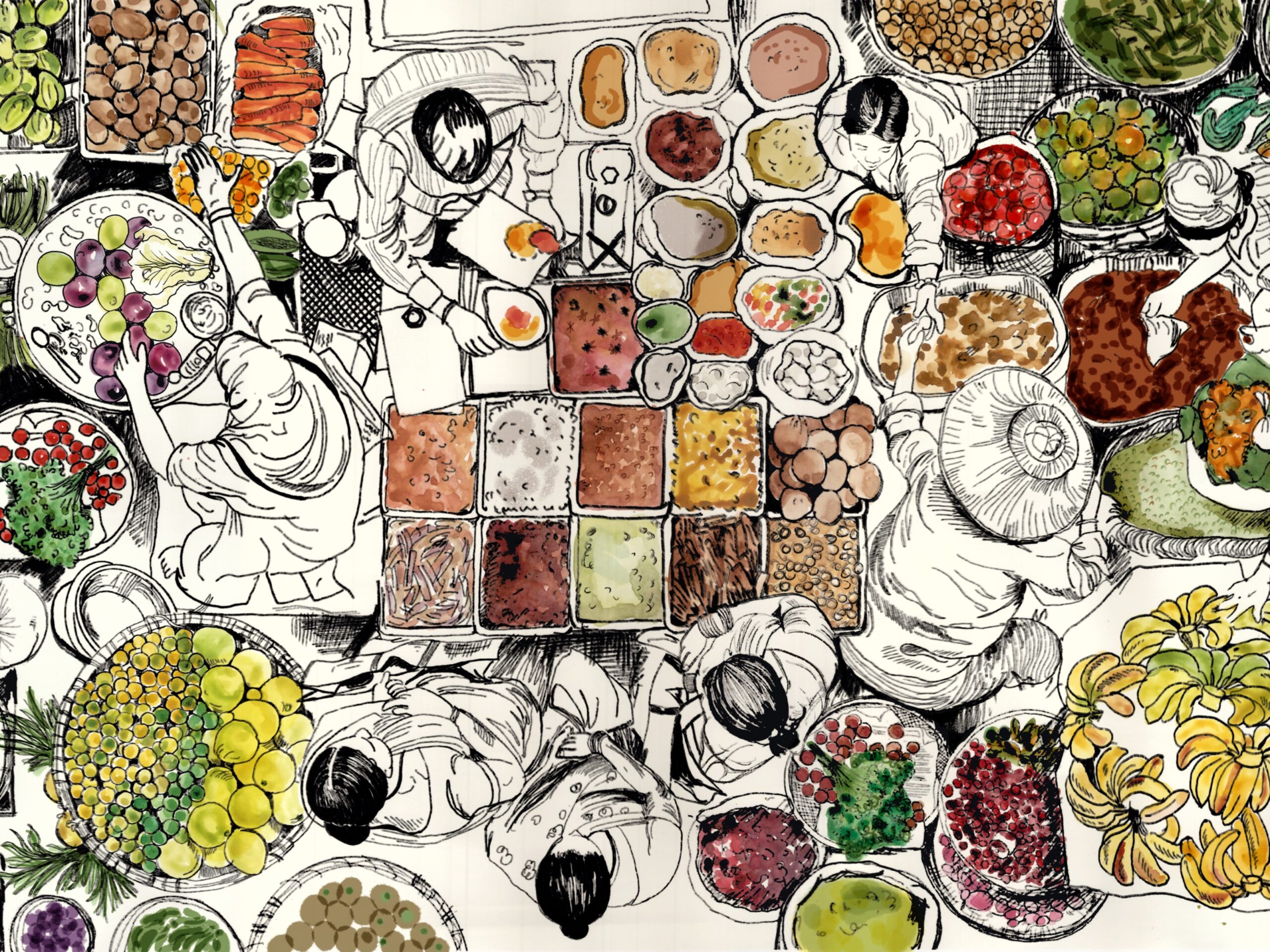

So it comes as no surprise that she never envisioned writing a vegetarian cookbook. There is some precedent, however. While not vegetarian, her first cookbook, Wet Market to Table, centred around the produce you’d find at Singapore’s fruit and vegetable stalls.

“In Singapore, if you were to say that you don’t eat meat, people would think that you either have a health condition that prevents you from doing so, or are hyper-religious,” she tells me. “Vegetarian food is its own category in Singapore, and it is mostly characterised by meat analogues fashioned out of wheat gluten rather than being vegetable-forward.”

Falling in love… with vegetables

Suffice it to say, vegetables weren’t her specialty when it came to cooking as a professional chef. It was only when she got married and moved to Australia – a country renowned for its produce – that she realised the true potential of vegetables. “I was working in Melbourne and was exposed to how thoughtfully crafted many vegetable dishes on the menu were,” she recalls. “They were dynamic, satisfying and very exciting to eat – them being vegetarian or vegan was beside the point.”

At the time, her diet was very meat-heavy. “Between my husband and I, we would buy kilos of meat and poultry every week,” she says. But that was a while ago – pre-pandemic and pre-bushfires. While she now lives in the Netherlands, the wildfires that ravaged Australia in 2018-20 forced Chia to look closely at the impact of her diet on the environment.

It was something she was conscious of, but could never pull the plug on. The bushfires were “the wake-up call that I needed”, she says. Now, she’s on a more balanced diet. Some days, she’ll use the thighs of the chicken she’s bought; another day, the carcass will flavour a vegetable-froward soup. And some days, the food she and her husband eat will be entirely vegetarian or even vegan.

“The idea now,” she outlines, “is to think of meat more as a seasoning to flavour dishes, or as a side dish to be eaten alongside rice and other dishes, rather than being the main thing on the plate.”

So while not vegetarian, vegetables are Chia’s thing. She stopped cooking in restaurants at the height of Covid-19 in 2020, a year after she published her first book. With the pandemic, she found more time to tend to her aspirations. “I felt a strong desire to document Asian traditions, recipes, and cooking techniques because we are so underrepresented in the English-speaking world.”

And so she set out to write her new cookbook, Plantasia: A Vegetarian Cookbook Through Asia. When I ask her why the meat-affecting-the-climate argument doesn’t extend to dairy, she says: “I wrote Plantasia with meat lovers in mind.” While the book contains plenty of inspiration for vegans and vegetarians, the mission is “not necessarily to convert anyone” – but instead “demonstrate the pleasures of vegetables” to encourage people to eat more greens.

“With people who might already find it a tall order to abstain from meat, I find it easier to wean them into loving vegetables by introducing a little egg, cream or butter in some recipes,” she explains. “That said, 95% of the recipes in Plantasia are vegan or vegan-friendly.”

Interviewing Asian culinary pioneers

Accompanying those 88 recipes – which include savoury soy milk with preserved mustard stem, thunder tea kimbap, and sambal goreng with charred coconut – are interviews with 24 chefs from across the world, discussing plant-based eating, Asian food and sustainability. Think Vietnamese chef Andrew Nguyen, Taiwanese chef Cathy Erway (both are James Beard-winning authors), Celestial Peach founder Jenny Lau, and Made in Taiwan founder Ivy Chen – to name a few.

Chia wanted to shake up the modern cookbook. What used to be your only source of recipes outside word of mouth or family diaries, are now crowded out by the endless stream of online recipes. “I like to think of the stories interspersed between the recipes as providing readers with the cultural context of some of the dishes, philosophies that underpin the way they cook and appreciate vegetables, as well as personal anecdotes – all of which I feel are extremely important to highlight,” she tells me. Indeed, some of the most popular cookbooks of late, such as Joanne Lee Molinaro’s The Korean Vegan Cookbook: Reflections and Recipes from Omma’s Kitchen are full of rich, intimate prose that elevates the recipes.

I ask her – perhaps cheekily – who were the sources of her favourite conversations. Her answer is what you’d expect (“I learnt so much from all of them”), but she does offer up the subjects she felt most strongly about. “A big highlight for me was understanding how traditional Asian diets evolved as Asians began interacting with people from the West,” she says.

Citing specific interviews, she continues: “Maori Murota [Japanese chef-author] outlines how the Japanese diet leaned more heavily towards meat and dairy after the Japanese people first came into contact with the Americans, whom they perceived to be of stronger builds and attributed that to their heavy meat and dairy consumption.

“A similar narrative was told by [Filipino vegan chef] RG Enriquez-Diez about the Filipino diet, which was influenced by the Spanish conquistadors’ zest for meat. There were also stories of how Asians started altering their diets when they left their homelands – Andrea Nguyen details how her family started eating lots of meat because it was abundant and affordable in the US. In the same vein, Zoey Xinyi Gong, who grew up in Shanghai, discovered how she was getting sick from her new American diet, and was forced to revisit her past eating habits in China.”

Taking inspiration from the best

“It was fascinating to recognise common threads throughout stories of Asians of seemingly disparate backgrounds, and to realise for myself that the journey of embracing vegetables is in fact one that also speaks of rediscovering my own heritage.”

Embracing vegetables is the mantra of one of Chia’s key gastronomic influences, Yotam Ottolenghi, the Isreali-British chef who – and I couldn’t describe it any better – “was pretty much the first chef to completely change the way people thought about vegetables and vegetable cookery”. Ottolenghi’s cookbooks and restaurants all champion vegetables, even in his meat-based dishes and recipes – and a similar aesthetic runs through Plantasia, albeit with a more Southeast Asian slant, of course.

Chia’s other culinary inspirations include Alice Waters, founder of California’s legendary farm-to-table eatery Chez Panisse, “for her work championing eating within your locality and emphasising the importance of ‘slow food'”; Dan Barber, co-owner of New York’s Blue Hill and author of The Third Plate, “for showing how sustainable diets are compatible with pleasure, and for demonstrating that the role of a chef or cook could extend beyond the kitchen”; and Malcolm Lee, owner of Singaporean Michelin-starred restaurant Candlenut and Chia’s former boss, “who showed me that food from Asia could stand proudly next to other celebrated cuisines around the world”.

Meat ‘substitutes’? It’s complicated

At several points in Plantasia – whose foundations are centred on flavour, accent, technique and texture, and which is divided into chapters highlighting different cooking methods – Chia touches upon meat substitutes, like in her conversations with Erway, Korean chef Sunny Lee and Sri Lankan chef Gayan Pieris.

Chia has spoken about her wish to empower vegetables for themselves – but she does think plant-based meat alternatives have a role to play. “In many parts of Asia, meat analogues such as wheat gluten or konnyaku are a big part of vegetarian cuisines,” she says, recalling what she said about vegetarianism in Singapore being pigeonholed into seitan-led meat analogues.

“That said, I’m not a fan of – and harbour scepticism towards – a lot of highly processed meats on the market right now. For example, some of these faux meat companies are owned by companies that support factory farming – so there seems to be quite a bit of greenwashing involved,” she explains.

She’s not a fan of calling it a meat substitute or alternative either. “Products such as tofu, tempeh, and young jackfruit are commonly described as ‘meat substitutes’ in the West, but when I was growing up in Singapore, I never understood them as such.” It echoes what Pieris tells her in the book: “Sometimes when there is a protein source, the easiest way for Westerners to wrap their heads around it is to label it a meat substitute.”

And it’s not that Chia doesn’t understand why they’re labelled this way, it’s more that she honours vegetables on their own merit. “Sure, they offer substantial chew and could replicate certain textural attributes of meat, but I never recognised these products as being substitutes for anything else. I loved them for what they are – doused in curry, slathered in sambal, simmered in stews,” she tells me, sounding very much like Amanda Cohen, chef-owner of Dirt Candy in New York City, whose dishes extolls vegetables as the main gastronomic event and Daniel Humm of Eleven Madison Park, also in NYC. It’s a topic that plant-forward, vegetable-centric food writers such as Alicia Kennedy discuss in detail, eschewing the idea that a diet without meat, dairy and eggs is one of deprivation and one that requires substitutes.

“When we call something a substitute for meat, we’re setting up unrealistic expectations. I remember coming across a headnote of a recipe describing how young jackfruit could be shredded and tossed in a sweet, sticky, savoury sauce to replicate BBQ pulled pork… only to be disappointed after trying the recipe out at how it was nothing like the real deal.”

She provides another example: “A quick internet search for tempeh recipes brings up countless recipes for ‘tempeh bacon’. It is such a shame to fixate on pushing tempeh into a ‘meat box’ when well-made tempeh is so creamy and rich in flavour that a quick marinade in turmeric powder and deep-frying brings out its natural flavour and texture, and transforms it into something I’d snack on obsessively.” (I would too, for the record.)

“I find that when we set aside these expectations for plants to deliver the exact same experience as meat does, that’s when we truly begin to respect and celebrate them for what they are.”

And celebrate she does. Plantasia features stunning recipes that feel as innovative and delicious as they are pretty. Her favourites? Grilled rice paper with tofu sisig, for one! And the charred Brussels sprouts with grapefruit and yuba (tofu skin).

“I’m proud of both because they aren’t vegan versions of existing meat or seafood dishes – they celebrate vegetables or plant-based products for what they are in an original way, are relatively easy to make, and are so incredibly delicious. Nobody would eat them and feel that they lack flavour or texture.”

Authenticity and approximations

This is a topic Chia has broached previously. In an interview with the South China Morning Post, she explained why she didn’t want to offer “veganised” versions of traditional meat- or seafood-based dishes. “To produce vegan laksa, to me, is like offering someone a second-rate substitute,” she said of the Southeast Asian noodle dish that uses seafood stock as a base.

But what of those vegans, then, who’d like to have a taste of the dish? Should they abstain from – or miss out on – eating these foods? “I’m sorry if this seems blunt or too direct,” she says politely, “but I think people who’d like to ‘experience these dishes’ would never truly be able to ‘experience’ them per se.”

She continues: “If a laksa’s flavour is defined by that of dried prawns and shrimp stock, and its texture is gritty from the texture of dried prawns (the word laksa translates to ‘spicy sand’), would someone be really experiencing ‘laksa’ if they were to consume a vegan version?”

However, she adds, it is possible for vegetarians and vegans to “experience very good vegan approximations of laksa”. The caveat? “For it to be as close a replica to the original as possible, the person who is preparing the laksa would have to be someone who has tasted the traditional, non-vegan version of the dish in the first place, so that he or she has an ‘authentic’ reference point.”

Okay, then, how does Chia feel about cultivated meat, which is biologically identical to meat – because it is meat, just from an animal cell? It can be a controversial food, given its relationship with fetal bovine serum and the novelty element. “I would be open to it,” she says. “But I reflexively recoil a little when I think about cultivated meat because the way I think about it, food is inextricably linked to our sense of place and identity. They are a gift from nature. What ‘terroir’ can cultivated meat purport to have?”

The MSG question

Speaking of controversy, one ingredient that bitterly divides people around the world is MSG (aka Monosodium Glutamate), renowned for its umami-lending characteristics and reviled for its (debunked) health ill-effects. It’s a compound originally that occurs naturally in many foods (Parmigiano Reggiano, for example) and has been used in Asia for centuries. Its use as a flavour enhancer in industrially processed food production has contributed to its bad rep in the West, alongside what came to be known as the unfortunately-named Chinese Restaurant Syndrome in the US in the 1960s.

“There seems to be a growing number of voices of Asians who live in the West who are advocating for MSG,” Chia points out. “I believe that it is mainly to encourage others to not demonise the ingredient, for it is something that is widely used in home cooking, restaurant cooking and street food.

“However, I do sometimes feel that this advocacy, when taken to the extreme, can paint all Asians in the same brushstroke. I certainly never had MSG around the house when I was growing up. My mom was Cantonese, and she believed strongly in the purity of flavours. I don’t have a problem with the use of MSG – as many have pointed out, it is a compound that is naturally occurring in ingredients such as meat, dried shiitake mushrooms, tomatoes and seaweed.

“What I have a problem with, however, is when people begin to use the powder as a crutch for flavour. For example, products such as soy sauce or miso are traditionally fermented over a long period of time. But, to cut costs, a company might cut the fermenting time short and add MSG to enhance the flavour.”

TLDR: there’s nothing wrong with using MSG, she says, but it’s “far better to harness it from natural sources” and introduce umami in your dish through cooking techniques.

Falling in love with… umami

It makes sense, then, that when I ask her what three pantry items people should never run out of, her list is umami-rich: fermented tofu, chilli crisp (a Szechuan chilli oil that features crunchy ingredients like fried shallots) and kecap manis (a syrupy Indonesian condiment that is often described as a sweet soy sauce).

“Fermented tofu, also known as Chinese cheese, is incredibly versatile. I use it to stir-fry veggies, dissolve it in water for a quick savoury broth, and add it to my stews and braises for more oomph,” she explains. “Chilli crisp is more of a finishing product in my household – I drizzle it over dumplings, or make a quick salad dressing with it. Kecap manis is great for stir-fries, dipping sauces, or for glazing roasted or barbecued items.”

Just the thought of these mentions makes me want to go straight into the kitchen and whip up something Asian-inspired. And that’s exactly what Chia wants for her readers, especially those who don’t live in Asia: “I hope that they will get a sense of the richness and depth of wisdom that Asia has to offer to the growing global conversations of vegetarianism and veganism, which are at the moment still very Eurocentric.”

As for the rest of us? “I hope that readers would realise that to eat vegetables is not to be deprived, but a celebration of everything that nature has to offer.”

Plantasia: A Vegetarian Cookbook Through Asia is available for pre-order online and in bookstores in select countries.