Switching to Meat Analogues Could Cut Emissions by 71%, Shows Analysis of 7,000 Households

4 Mins Read

Making modest ingredient swaps could help cut food emissions by 26%, but larger switches – like replacing meat with plant-based analogues – can bring about a 71% reduction.

The food system only trails behind the energy sector in terms of planetary impact, accounting for a third of global greenhouse gas emissions. Study after study has shown that animal-derived products have a much heavier footprint, with one suggesting that meat alone accounts for 60% of the food system’s emissions.

Now, new analysis – claimed to be the most detailed research into the climate impacts of a country’s food habits – has revealed that switching from meat to plant-based analogues could cut emissions by as much as 71%.

Researchers from Imperial College London’s School of Public Health and the George Institute for Global Health looked into comprehensive emissions data and sales for over 22,000 supermarket products in Australia, which are typical of the western diet of many countries. Covering the annual grocery purchases of 7,000 households, the research calls for significant dietary change in high-income countries to meet global climate targets.

Meat and dairy the biggest GHG emitters

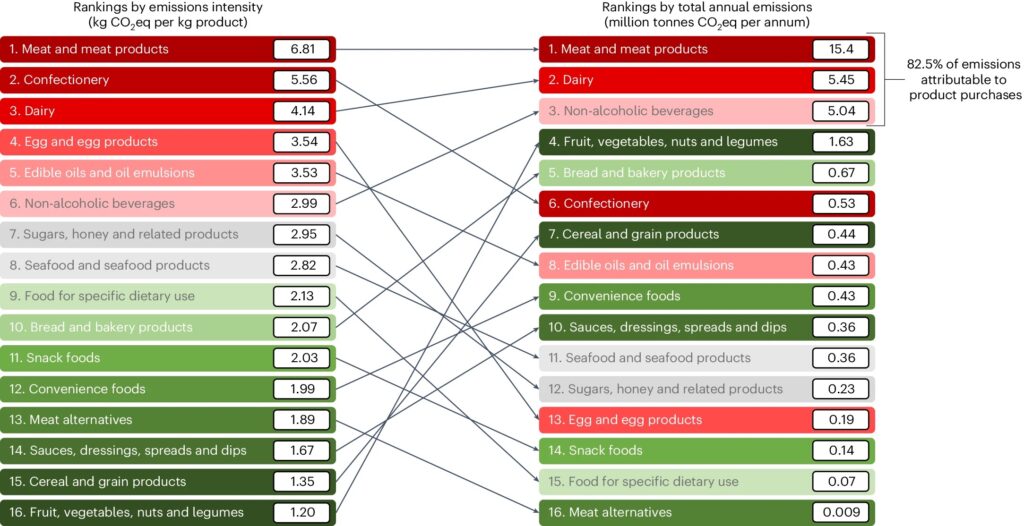

The study used data from the George Institute’s FoodSwitch database from 2019 as well as global environmental impact datasets, assigning foods to 16 major categories, which were further divided into 74 minor categories and 703 sub-categories.

For example, bread and bakery, meat and meat products, and dairy were the main categories, further divided into minor subsets of bread, processed meat, and yoghurt and yoghurt drinks, and then separated by sub-categories like white bread, meat pies, and non-dairy yoghurts.

The research revealed that replacing higher-emission products with “very similar” lower-carbon ones (from high-GHG to low-GHG breads, for example) can reduce emissions by as much as 26%, while more drastic switches to “less similar” foods (from high-GHG garlic bread to low-GHG white bread) could result in a 71% reduction.

The differences are quite pronounced when you analyse animal products like meat and dairy. Meat alone makes up for nearly half (49%) of the 31 million tonnes of GHG emissions analysed, despite only making up 11% of all grocery purchases. Dairy is the second-largest contributor (17%), though these products accounted for 21% of product sales.

Meanwhile, fruits, vegetables, nuts and legumes contributed to 5.2% of all emissions, despite making up a quarter of all purchases. And meat analogues were the lowest-emitting of all product categories, responsible for just 0.03% of all emissions (albeit representing 0.07% of purchases). This is why swapping from a meat-based lasagna to a vegetarian one can lead to the 71% emissions cut mentioned above.

While the researchers aim to show that even small changes can foster climate-conscious eating habits, a glimpse at the difference between dairy and non-dairy shows how much vegetarianism differs from fully plant-based eating. Going from Aldi’s sweetened Greek yoghurt with honey granola to Coco Tribe’s gluten-free vanilla coconut yoghurt can reduce emissions by 77% (the research excluded brand names, but the product descriptions point to these companies).

Could carbon labelling help consumers make climate-smart choices?

“Consumers are willing to make more sustainable food choices, but lack reliable information to identify the more environmentally-friendly options,” said Gaines. She and her co-authors are calling for on-pack carbon labels on all packaged food products to help consumers make informed choices.

“The results of our study show the potential to significantly reduce our environmental impact by switching like-for-like products,” she added.

The study proves that incorporating sustainability targets in national food policies could directly help reach global climate goals, without burdening consumers, according to Paraskevi Seferidi, a research fellow at the School of Public Health. “This is why we are urgently calling for robust legislation that targets high-emission food products,” she said.

The combined health and environmental costs of the global food system are estimated at between $12.7T and $15T. According to the UN Food and Agriculture Organization, “unhealthy dietary patterns” are the major contributor to these hidden costs.

“There is currently no standardised framework for regulating the climate or planetary health parameters of our food supply, and voluntary measures have not been widely adopted by most countries,” said Bruce Neal, executive director of the George Institute Australia and an Imperial College London professor. “This research shows how innovative ways of approaching the problem could enable consumers to make a real impact.”

Based on the research, the George Institute has developed a free app called ecoSwitch, which is currently available in Australia. “Shoppers can use their device to scan a product barcode and check its Planetary Health Rating, a measure of its emissions shown as a score between half a star (high emissions) to five stars (low emissions),” explained Neal.

He added: “EcoSwitch is a much-needed first step, but our vision is for mandatory display of a single, standardised sustainability rating system, on all supermarket products.”