Plant-Based Food Offers Far Better Returns on Climate Investment Than EVs or Green Energy: Study

6 Mins Read

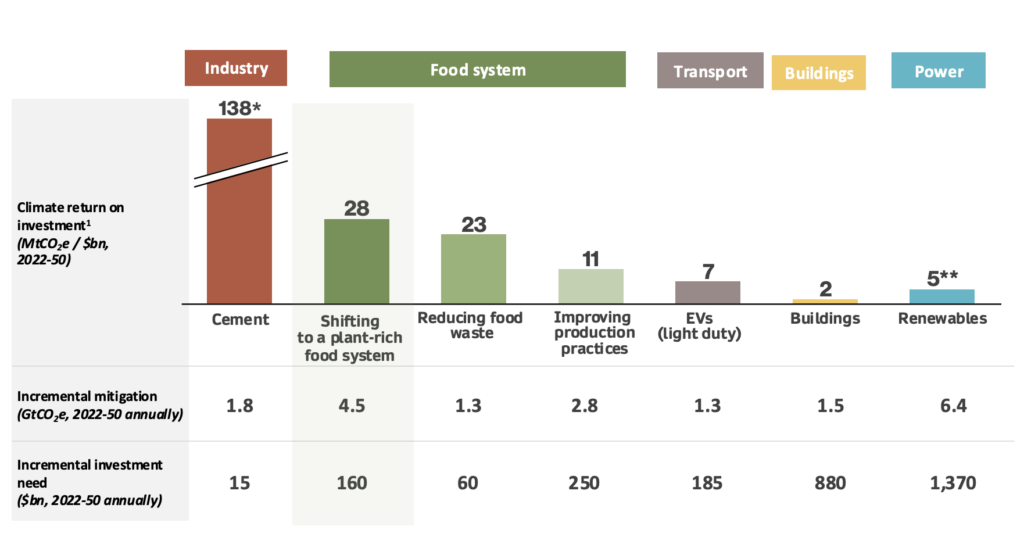

Investing in a plant-based food system offers much greater emissions cuts per dollar than renewable energy or electric vehicles, shows a new report.

If governments and investors put the same amount of money into plant-based food as they do electric vehicles (EVs) and green energy, the former will offer the greatest returns on investment in terms of reducing emissions.

Every $1B pumped into companies and strategies focused on transitioning to a plant-based food system would result in the mitigation of 28 million tonnes of CO2e, a return five times higher than renewable energy (five million tonnes) and EVs (seven million tonnes).

The emissions savings from financing plant-based progress also far outweigh the returns on investment into improving livestock production practices, the report from Tilt Collective and Systemiq found.

“Shifting to a plant-rich food system represents a spectacular pay-off as a climate investment – the outsized climate benefits are clear,” said Tilt Collective CEO Sarah Lake, who previously co-founded the research firm Madre Brava.

The food system takes up around a third of the world’s emissions – by the UN FAO’s estimate, it was responsible for 13 gigatonnes of emissions in 2019, more than the industry and transportation sectors combined.

Tilt Collective, whose work is centred around the protein transition and addressing the ills of industrial livestock agriculture, has released the report to coincide with the ongoing Climate Week NYC (September 22-29). It underscores the critical underfunding of the plant-based food industry, given its outsized impact on climate change mitigation.

“While we of course need investments in other sectors and food solutions as well, the data is undeniable that investments in plant-rich food systems, and shifting consumption and production patterns, offer exponentially more emissions reductions for the money spent,” said Lake.

Investing in plant-based food more valuable than livestock improvements

The report argues that current ways of producing food are highly inefficient, using up 65% of the world’s freshwater and contributing to almost all (90%) of deforestation. This is largely thanks to livestock farming, which alone accounts for 57% of the food system’s emissions, a figure twice as high as that for plant-based food.

Animal agriculture currently occupies 80% of the world’s land, but only provides 18% of its calories and 38% of its protein supply. It’s also leading to a rise in non-communicable diseases, elevated antimicrobial resistance, and pandemic risks, contributing to the $9.3T of hidden costs caused by “unhealthy dietary patterns”, according to the FAO.

Moreover, if meat consumption continues to grow and current livestock production models remain unchanged, we can only feed 3.4 billion people while respecting planetary boundaries, less than half of the eight billion people living across the planet today, and a third of the 10-billion-strong population expected by 2050.

Many meat and dairy producers are looking into ways to lower their methane impact and, subsequently, climate footprint. A lot of money has been poured into this strategy, and it does have some merit, but not nearly as much as the returns you get when you invest in transitioning to plant-forward food system.

Such a shift towards a plant-forward food system offers 2.5 times more emission reductions than improving on-farm livestock and crop production systems – the latter would cut emissions by 11 million tonnes per billion dollars invested.

In fact, the return on investment for enhancing production practices is lower than addressing food waste too, which itself accounts for five times more emissions than the entire aviation sector. Project Drawdown has named food waste reduction as the top climate solution to curb emissions in line for a 2°C future – and this report (focused on a 1.5°C target) shows that this can eliminate 23 million tonnes of emissions per $1B.

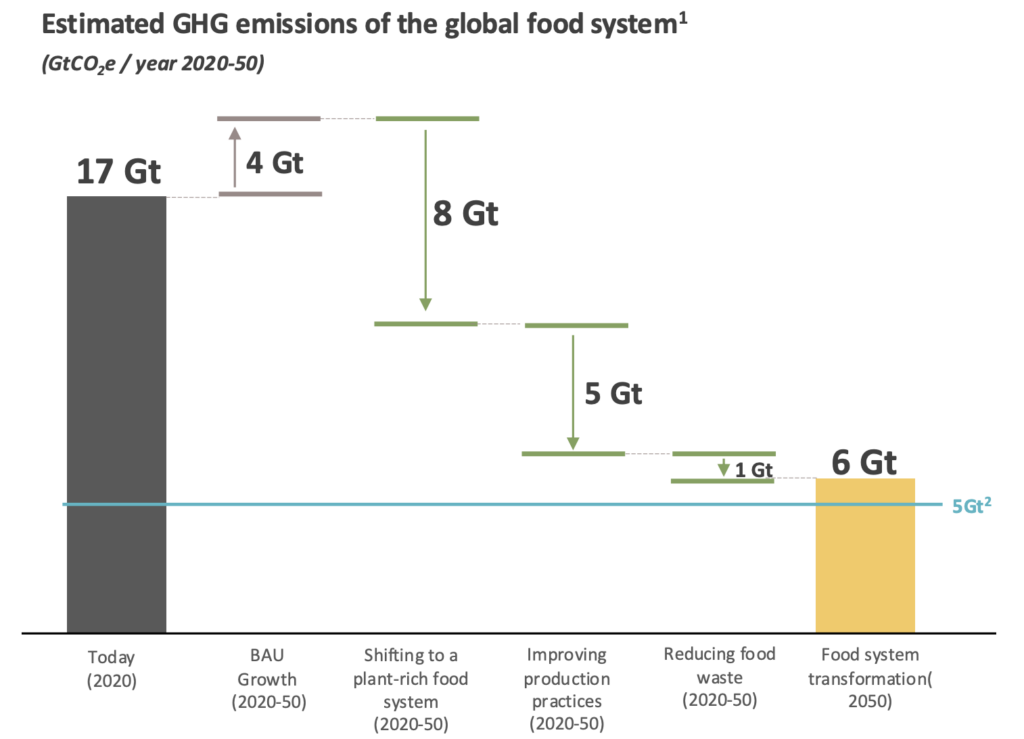

Tilt Collective and Systemiq outline the potential of a high-ambition scenario – one where over 80% of the population adopts the Planetary Health Diet proposed by the Eat-Lancet Commission by 2050, food waste is halved, up to 30% of livestock interventions for emissions reductions are implemented, and biochar is established as a sequestration strategy.

Business as usual would mean our agricultural emissions rise to 21 gigatonnes by 2050 – but this high-ambition scenario would slash that by 71%. Improved livestock and crop management would help bring emissions down by five gigatonnes, food waste reduction by one gigatonne, and a plant-based transition by eight gigatonnes.

“While advancing all transitions is essential to meeting our climate goals, the investment opportunity in a plant-rich food system is impossible to ignore,” said Christine Delivanis, head of nature and food at Systemiq, which is focused on systems change towards a low-carbon economy.

Multi-pronged benefits could be unlocked by philanthropic funding

It’s not just the emissions potential. A plant-based transition would bring co-benefits that other sectors can’t. For starters, there’s the land sparing.

The food system is set to use up 4.1 billion hectares of land by 2050 if things stay the same, but turning to a Planetary Health Diet would free up nearly 1.6 billion hectares. This can slow down biodiversity loss by 40%, and unlock the potential to sequester two to four gigatonnes of carbon by 2050.

This would also save 1,100 cubic km of water by 2050, equivalent to current freshwater withdrawals from the US and China. Essentially, water use could be cut by a third, annual savings from water bills could be down between $140-240B for farmers, and water pollution from nutrient runoff will be slashed by 40%. Likewise, fertiliser use will reduce by 40%, and bring savings equivalent to the annual manure production of 350 cows.

In addition, moving to plant-forward dietary habits would bring a host of health benefits. It would increase 150 million years of healthy lives and save $3.4T in economic productivity annually by 2050 from these gains, since malnutrition, obesity, antimicrobial resistance, and pandemic risks will all fall.

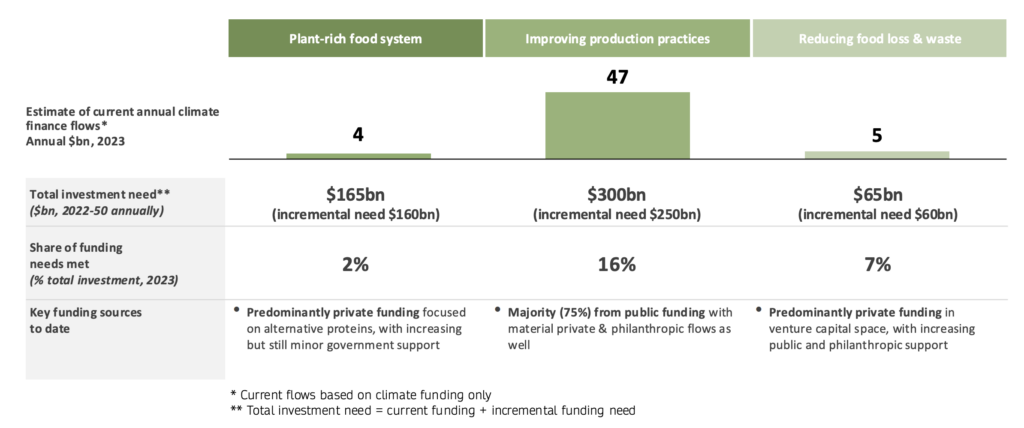

The problem, though, is that the shift towards a sustainable food system is severely underfunded. On average, alternative proteins are currently receiving $3.4B in public and private sector investment every year, versus the $46B sent to improving production systems and $5B to food waste management.

To put that into context, investments in renewable energy startups reached $11.6B in 2023 – and that’s just VC money. The Tilt Collective/Systemiq report says the alternative protein transition needs $160B in incremental funding annually until 2050, which means the current yearly total is at a meagre 2%.

Philanthropic organisations can be a catalyst here. An initial investment of $250-500M from this sector could unlock $4-7B of public and private finance. This would also create strong, science-based narratives, break silos between food system pillars and communities, and derisk investment in the sector.

One such organisation is the Bezos Earth Fund, which has set up a $1B Future of Food initiative, through which it’s investing $100M in three alternative protein research hubs globally. Andy Jarvis, director of the Future of Food initiative, said the scale of philanthropic investment is quite small.

“We see this as a high-leverage opportunity for philanthropy to catalyse action by governments, the private sector and civil society to meet climate goals, deliver benefits to nature and boost human health and nutrition,” he added.