Serving Plant-Based by Default in Colleges Can Cut Emissions by 24% and Meat Consumption by 81% – Here’s Why

8 Mins Read

A recent trial revealed that serving plant-based options by default in college and university campuses can present significant benefits for the environment – the people behind the study explain why.

Last year, catering giant Sodexo revealed the results of an intervention study at three college campuses in the US. Led by behavioural science non-profit Food for Climate League (FCL) and dietary change think tank the Better Food Foundation, the trial explored what would happen if cafeterias offered plant-based dishes as a default option over meat-centric ones.

The researchers found that, when only vegan dishes were presented to college students – with a separate sign informing them that they could order a meat-based one instead – there was a significant uptick in the adoption of plant-based foods, a decrease in meat consumption, and an improved climate footprint.

With an estimated 235 million students eating around 148 billion meals each academic year, the greenhouse gas emissions add up. But if you serve them vegan food by default, it can result in as many as 81.5% more students eating plant-based meals in cafeterias, which in turn can reduce 23.6% of GHG emissions.

This is because meat’s emissions are twice as high as plant-based foods, with research suggesting that the latter can reduce emissions, water pollution and land use by 75% compared to meat-rich diets. “Having plant-based foods isn’t a buzz or a trend, it’s a need and a demand that we deliver with creativity and flavour,” Sodexo’s US Campus CEO, Brett Ladd, said at the time.

“We also recognise that reducing our animal-based food purchases is a key part of our carbon reduction strategy,” he added. “Having the plant entrée as the default demonstrated that people are open to trying and enjoying plant-based options with the added benefit of helping the planet.” The caterer has committed to making 50% of its campus menus plant-based by 2025, as part of a wider net-zero strategy for 2040, which it says is running ahead of schedule.

How default plant-based options change eating habits

The trial was carried out in three universities: Tulane University in New Orleans, Lehigh University in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania, and Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute in Troy, New York. The researchers assessed one dining hall station, that contained eight pairs of dishes (one plant- and meat-based each): the control day saw both options being presented side-by-side, while on the intervention day, only the plant-based dishes were put out, with students needing to request the meat version if they wanted.

During the design phase of the intervention, Food for Climate League collaborated with Sodexo and the Better Food Foundation to identify test sites with a range of demographics, develop a recipe rotation specifically for the test, and keep the testing timeline to under one semester. “We also opted to test defaults at dining hall stations that already serve entrées containing meat in order to reach the widest number of students,” explains FCL design researcher Stephanie Szemetylo.

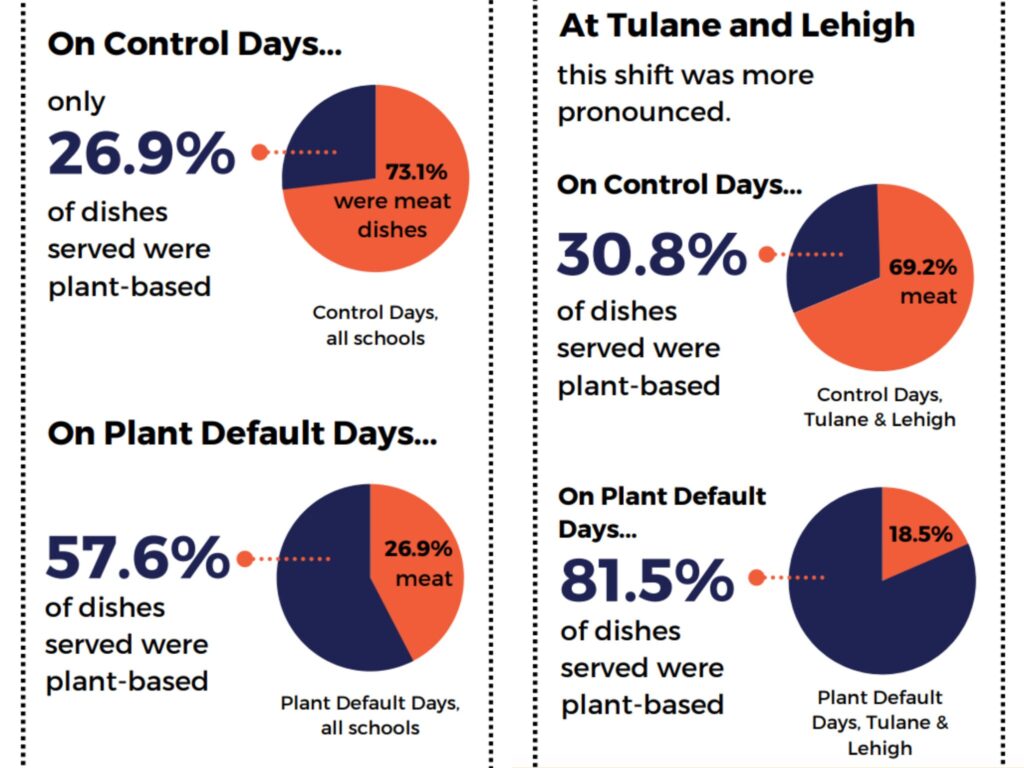

The research was the latest in a host of choice architecture studies, but was described as the first of its kind, given it covered multiple universities in an all-you-can-eat setting. In absolute terms, there was a 58.3% combined increase in the number of plant-based dishes served across the three campuses. On average, the take rate of vegan dishes jumped from 26.9% to 57.6% on days when they were the default option, but at Tulane and Lehigh, the change was even more pronounced, with the figure climbing up to 81.5%.

The researchers took into account a spillover effect, which indicates that students who would have visited an intervention station on a control day avoided it on the plant-based default day in search of meat options elsewhere in the dining hall. But even if all of them got a meat-based meal, there would still be around a 21% reduction in meat dishes served overall as a result of the intervention.

Why default plant-based options in cafeterias work

So why does this work? “There are many aspects to our environments that impact our decisions, whether we are aware of them or not. Editing the choices you present to people, and how they are presented, can impact the choices they make,” explains FCL founder Eve Turow-Paul.

Reflecting on the study, she notes: “We showed that a very slight change in the way menu options are offered can have a major impact on food choices, ultimately leading to selections that are better for the planet. In addition, this change was, for the most part, celebrated by both patrons and the serving staff.”

Szemetylo adds: “Most importantly, the success of defaults relies heavily on the proper implementation of the intervention by dining hall operators, line cooks, and servers. With incorrect implementation, the impact of the default on dish choice vanishes.” At Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute, for example, there were inconsistencies in implementation, which meant that there was barely any improvement in plant-based intake (it went from 26.3% to 27.2%).

There has also been a lot of discourse around using the term ‘plant-based’ versus ‘vegan’. In 2018, research revealed that for the 2,201 Americans surveyed, ‘vegan’ is the most unappealing descriptor for groceries, chosen by 35%. A year later, analysis showed that terms like ‘plant-based protein’ (56%) and plant-based (both 53%) are much more appealing than descriptors such as ‘vegan’ (35%).

“The goal with any food label is to be as inclusive as possible,” explains Szemetylo. “A very small percentage of the global population is vegan. A larger portion of the population will eat foods that are plant-based. And an even larger population will eat foods considered to be healthy, sustainable, or just plain delicious.”

She continues: “It’s important to consider your audience when labelling foods. At a college campus, ‘plant-based’ may perform well, while in other settings, it may ostracise many… Generally speaking, we recommend focusing on flavour over all else. ‘Vegan’ speaks mostly to those who hold that identity and seek visual cues on menus and food products to identify what is animal-free. Unfortunately, that term may turn off those who are not vegan, as it can signal that the menu option is not intended for them.”

‘Underseasoned tofu’ a thing of the past

Turow-Paul suggested that foodservice and campus chefs are very interested in decarbonising their menus, but there are a few key hurdles. “Often, sustainability advocates – from corporate offices to government agencies – are siloed in their work. We need all staff to see sustainability as their responsibility, whether it’s in their titles or not,” she says.

“Second, while there are many how-to resources on ways to make these changes, the motivation and emotional engagement are often missing, which is a challenge that FCL’s work aims to tackle. Third, the resources are limited, especially on-site staff, so any support we can provide to make this easy for them will help.”

But despite openness from staff and students alike to shift towards plant-forward choices, the study found that eating and serving meat continues to be the social norm in campus dining, signalling an untapped opportunity for interventions – like defaults – to change consumption behaviour. Szemetylo believes that “the myth that sustainable meals don’t taste good” is holding decarbonisation efforts back.

“Often, we speak with chefs who think that in order for their food to be climate-friendly, it has to be less flavorful, and that ultimately, people won’t want to eat it. Nothing could be further from the truth,” she states. “Eating more sustainably means greater diversity in ingredients that are full of flavour. We need to move past this idea that we’re asking everyone to serve under-seasoned kale and tofu.”

Embrace cultures, understand audiences, and educate staff

FCL has developed a follow-up pilot to its research, which comprises motivational training for front-line staff and an implementation toolkit for foodservice operators. “We have already secured some initial funding, but are looking for an additional $80,000 to get this work off the ground, and another $120,000 to run the pilot, analyse the results, and widely disseminate our findings and tools,” says Turow-Paul. “Beyond that, we are always looking for implementation partners, be they foodservice operators, city leaders, consumer packaged goods companies, retailers, and more.”

Szemetylo explains that leaders across business, public policy, and institutions must begin to understand and leverage the role of food in mitigating emissions and improving human health. “We need all kinds of people to understand the success of this simple yet effective behaviour change strategy – from eaters, to plant-based advocates, behaviour change researchers, food industry decision-makers, and anyone who is interested in encouraging sustainable food choices.”

The study identified key opportunities for foodservice operators. Adopting a plant-based default serving approach even at just one station can improve the sustainability credentials of their sites, but engaging staff early to facilitate more accurate implementation, and leveraging their relationship with diners is key. The researchers also confirmed that gender plays a role in meat consumption norms, with women more open to adopting plant-based options – so understanding audiences is key.

Plus, caterers can increase satisfaction with vegan dishes by leveraging local food culture and maximising verbal and visual dish appeal. For example, the meals used in the trial include lentil patties with mushroom Valencia casserole, tofu bulgogi rice bowls, sesame-ginger tofu tikka masala, veggie burritos, and lentil, olive and mushroom spaghetti.

Sodexo has begun implementing a shift to plant-based defaults in its universities, having built the Plants-by-Default model into its core station’s pre-selected menus from the fall 2023 semester, which are provided to over 400 university dining operations. “We undertook this study to help nudge Sodexo’s own operations to adopt plant-based defaults more widely across our operations, and we are already seeing the direct large-scale impact on institutional dining that we set out to achieve,” said Lisa Feldman, director of culinary services at Sodexo.

“Foodservice leaders need to integrate defaults as part of their climate action plans and decarbonisation targets,” says Szemetylo. “To do so – and I cannot stress this enough – we need to support on-site staff in the implementation. Every site has its unique culture and constraints that influence how defaults can translate.

It’s critical to engage with on-site staff to share the purpose of defaults, co-create solutions with them to implement defaults in ways that provide the least amount of disruption to day-to-day operations, and build intrinsic motivation so that onsite staff can become sustained stewards of these strategies.”