Not ‘Mylk’: Plant-Based Industry to Fight New UK Proposal That Could Force Alt-Dairy Products to Change Their Labels

7 Mins Read

A British trade standards group is pushing for guidance that would ban the use of alternative descriptors like ‘mylk’, ‘cheeze’, or ‘yoghurt-style’ on plant-based dairy packaging.

The UK could soon issue new guidance prohibiting plant-based dairy companies from describing their products as alternatives, with terms like ‘not milk’ or ‘cheeze’ not allowed on product packaging.

Plant-based brands are already banned from using dairy-related terms like ‘milk’, ‘yoghurt’ and ‘cheese’ on labels thanks to a 1987 EU law that has been retained by the UK post-Brexit. But the new rules could mean these companies wouldn’t be allowed to use alternative descriptors either, in a move that has been described by industry stakeholders as “draconian”.

It is part of a years-long effort from the Information Focus Group (FSIFG), a group of trading standards officers that alternative protein advocacy organisation ProVeg International has previously called “obscure”. The argument isn’t new: the FSIFG says these labels cause confusion among consumers, although consumer surveys have played this down.

With the new guidance thought to be imminent, the Plant-Based Food Alliance UK (PBFA) will make a last-ditch attempt this week to ask UK environment secretary Steve Barclay to intervene, with a letter explaining how this would push up prices in a market hit hard with the cost-of-living crisis, and requesting for the guidance to be dropped and regulations reviewed.

No ‘milk’, no ‘mylk’, and no ‘m*lk’

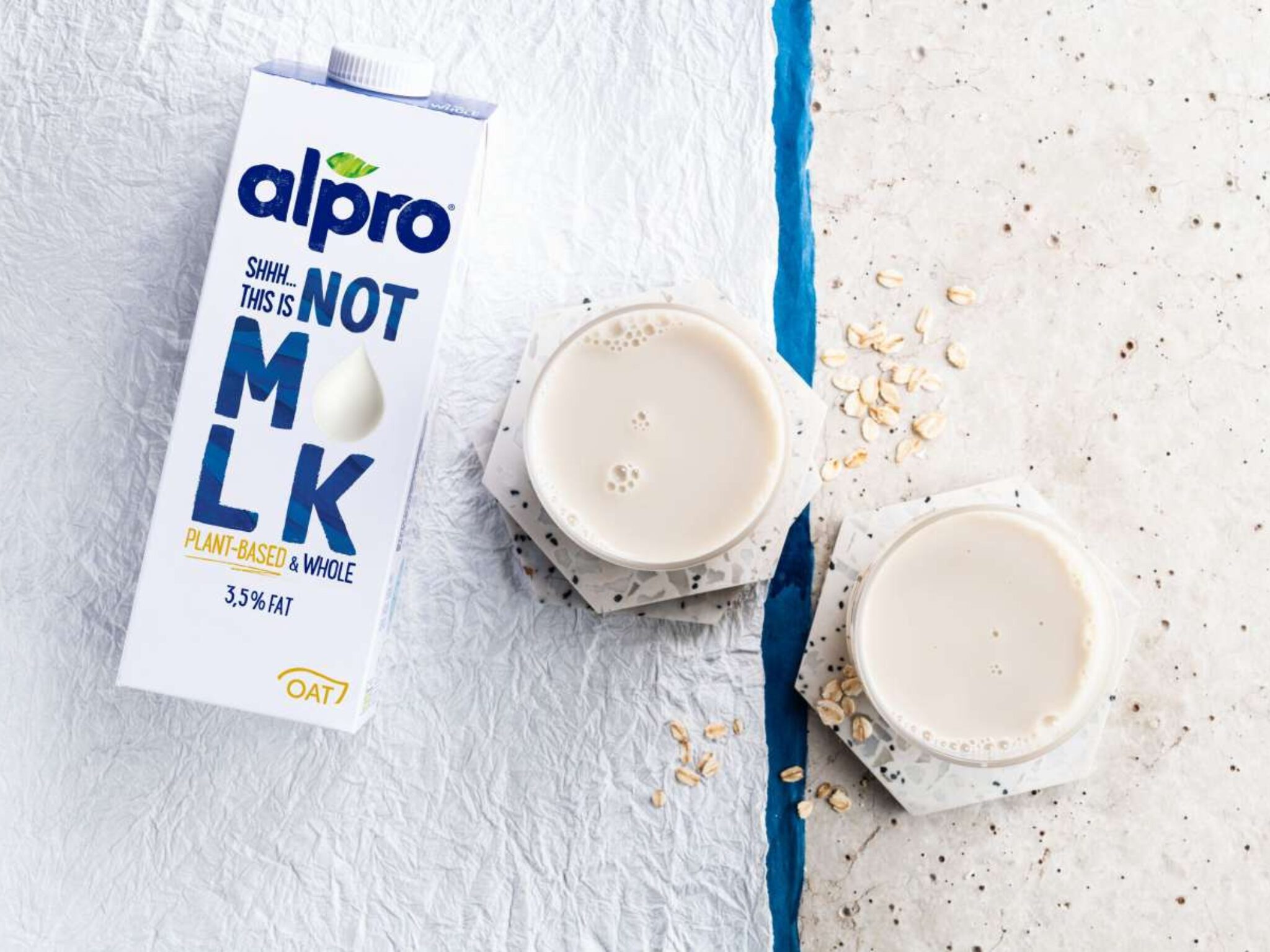

There were murmurs about the new guidance as far back as January last year, when the FSIFG issued the proposed guidance to local Trading Standards officials in the UK. The group called for a ban on brand names on supermarket shelves and in coffee shops, including Flora Plant B*tter, Mighty Not Milk (previously M.LKology), Good Hemp – Oat + Hemp Milk, Qurkee M’LK, and Alpro This Is Not M*lk.

The new rules outlaw plays on words, like ‘m*lk’ or mylk’, terms like ‘not milk’ accompanying images evoking milk, phrases including ‘alternative to’, ‘yoghurt-style’, ‘Cheddar flavour’, etc., as well as ‘semi’ or ‘whole’ to describe the fat content in plant-based milk, as is done in conventional milk.

“Technological innovation is leading to the construction of products offered as alternatives to conventional foods of animal origin,” the FSIFG was quoted as saying by the Guardian. “It is important that products are clearly distinguished, understood and nutritional differences are not confused.”

However, ProVeg argued last year that the guidance was not subject to public consultation, and there was no communication with the plant-based sector either (though this has been disputed by some sources). But that would come as little surprise if you take Greenpeace’s suggestion that the dairy industry had been lobbying for these rules to be implemented.

“We’re trying to come up with a fair and balanced view on what the legislation says, and if certain parts of the market don’t like that it’s up to them to lobby the government to change the legislation,” David Pickering, FSIFG member and lead food standard officer at the Chartered Trading Standards Institute, told Greenpeace’s Unearthed publication.

Despite objections from the vegan sector, the latest version of this guidance (dated January 2024) has not been watered down. It suggests that plant-based companies should not use homophones, asterisks, or other wordplay. While foods like custard creams and salad cream are fair game, ‘vegan mozzarella’ and ‘soya yoghurt’ are not. What should companies call these instead? “Vegan soft-white balls with a light cheese flavour” and “soya dessert fermented with live cultures” are the FSIFG’s suggestions, respectively.

“The FSIFG is an independent group that does not have the power to change existing regulations. It merely advises trading standards officers on how they should interpret the current rules,” ProVeg CEO Jasmijn de Boo told Green Queen. “The group’s membership is not transparent, and it does not have a public website.”

They added: “It is challenging for businesses to engage effectively with the FSIFG as it does not follow the usual government processes of open, transparent consultation.”

‘Draconian’ rules for consumers who are not confused

“This move will make us one of the most draconian nations in regards to what we can and cannot call these sorts of products,” PBFA CEO Marisa Heath told Unearthed last year. “Consumers know what they are buying and they are not stupid, it should be left to them to make their choices in the supermarket.”

This has been echoed by oat milk leader Oatly, whose UK and Ireland manager Bryan Carroll has described the assumption that people won’t be able to tell the difference as “frankly insulting”, questioning whether the UK wanted to be a country with the “most draconian rules about how we describe our food and drink”.

A 2022 survey by ProVeg found that only 17% of Brits were confused about whether ‘plant-based’ foods contain dairy or eggs, which came two years after a study found that consumers aren’t more likely to think vegan products have animal origins if their names have conventional terms. In fact, the latter added, “omitting words that are traditionally associated with animal products from the names of plant-based products actually causes consumers to be significantly more confused about the taste and uses of these products”.

Likewise, a 2,000-person poll published last month found that only 20% of Brits have confused plant-based foods with animal products due to branding or labelling, although it noted that 38% of UK consumers believe vegan companies should not be allowed to use animal-related terms.

Heath believes the implementation of the new guidance would harm the food industry. “At the time when we should be encouraging consumers to make more sustainable choices… this is a bad move,” she told the Guardian. “Major retailers will have to rename their own-brand plant-based products. This will cause unnecessary time and financial costs in an industry that is already doing its best during the cost of living crisis. This could then have an impact on consumer prices too.”

“In 2023, we didn’t receive a single complaint of consumer confusion,” said Ian Hepburn, marketing director at Upfield UK and Ireland, which makes the Flora butter range and I Can’t Believe It’s Not Butter. “We are baffled by these proposed restrictions which do nothing but add bureaucracy to an outdated EU law.”

The guidance will bring ‘severe consequences’ for companies

If imposed, the proposed rules would be tougher than even the EU’s, which only bans conventional dairy terms like ‘milk’ and ‘cheese’, but not alternative uses or plays on these words. In the US, in fact, the FDA now allows plant-based milk brands to use the term ‘milk’ to describe their product (though there are disputes over voluntary nutritional labels). The new regulations would hinder the UK’s plant-based milk sector: market leader Alpro was already a key driver behind the milk category’s retail decline last year, with sales falling by £13.7M.

“One of the reasons the UK voted to leave the EU was to free itself up from burdensome regulations like the legacy law that the FSIFG is interpreting. But that law is no longer fit for purpose. We need to be encouraging the plant-based food market where we can, not seeking to restrict it,” said de Boo.

The guidance will be shared with trading standards officials nationwide if passed through at the FSIFG’s next meet, and restrictions could be in place by Easter. However, a spokesperson for Defra told the Guardian: “This is a draft opinion from a group who are independent of government. There are no plans to change existing legislation in this area.”

“The guidance is highly likely to be passed,” said de Boo. “The consequences for companies – especially SMEs – will be severe. Businesses will be forced to rename well-known products and re-design packaging, resulting in significant financial costs, waste, and potentially in reduced sales as product recognition from consumers is damaged.”

The development comes around the same time that UK prime minister Rishi Sunak – who has been criticised for his climate inaction – attended a protest with a group that has posted climate change conspiracy theories and campaigns against net zero. Sunak has infamously called for a “more pragmatic, proportionate and realistic” to the UK’s net-zero plans for 2050, without outlining what that entails.