5 Mins Read

Pasture-raised cattle, which mostly feed on grass in grazing lands, have been thought of as a more “ethical” form of beef than those raised in feedlots – but the former may not be as climate-friendly as many proponents argue, according to a new study.

Grass or grain – how do you like your beef?

Whatever your answer is, it’s unfortunately not as ethical or climate-friendly as you think, if you believe a new study by Californian climate research centre the Breakthrough Institute. Published in the Plos One journal, the research reveals that pasture-raised beef – whose advocates tout its more ‘natural’ production method – is actually much worse for the climate than grain-fed beef raised in feedlots, when you account for the land use.

The authors analysed the footprint of 100 beef operations across 16 countries, which included production emissions, soil carbon sequestration from grazing, and carbon opportunity costs – the potential carbon sequestration that could occur on land if it were not used to produce that specific food.

Why pasture-raised beef is bad for the climate

TIll now, most studies have looked at the greenhouse gas emissions of beef production to determine their climate impact, but this research went beyond that to include how much lunch is used for cattle grazing.

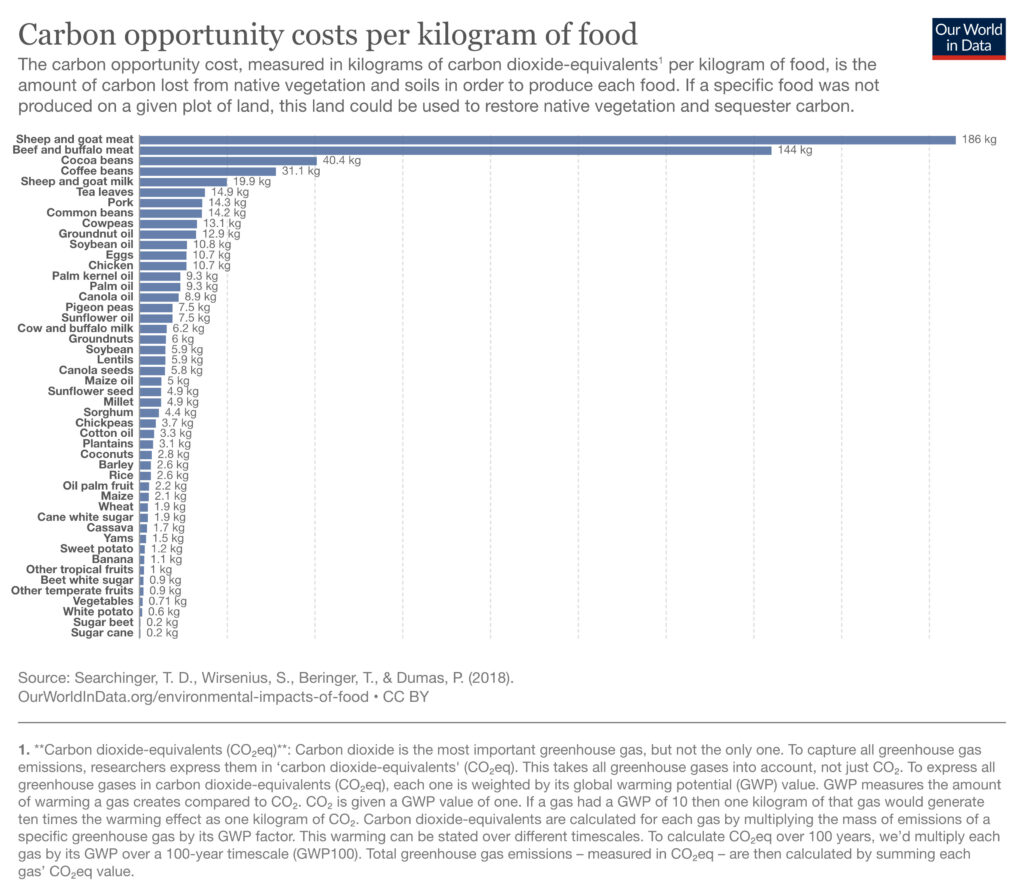

Previous research has revealed how beef emits 99kg of greenhouse gases across its production supply chain, which is twice more than the next food on the list (dark chocolate). But when it comes to carbon opportunity costs, the discrepancy is even greater. Beef (along with lamb) is second only to sheep and goat meat here, with 144kg of CO2e per kg of beef lost – the next on the list, cocoa beans, have an over 3.5 times lower impact.

But within the different kinds of beef, the Plos One study found that pasture-finished operations have a 20% higher GHG footprint than grain-finished ones. And when accounting for soil carbon sequestration and carbon opportunity costs, the total carbon footprint of pasture-raised operations was 42% higher.

This difference primarily lies in the finishing stage, since the amount of pasture required for pasture-raised cattle is naturally much higher than what’s needed for feedlot operations. Additionally, an increase in land use intensity is associated with a higher overall carbon footprint. The authors found that a 10% rise in intensity leads to 4.8% greater production emissions, but a 9% higher carbon footprint after incorporating land use effects.

In fact, the carbon opportunity costs were 130% larger than production emissions, which underlines the importance of integrating this metric in sustainability assessments of beef production and during the development of climate mitigation strategies.

Shaping policies, consumer choice and use of different metrics

The study notes how pasture-finished operations are responsible for a third of all beef, with grain-fed systems accounting for a further 15%. The rest is represented by other methods, like mixed crop-livestock production.

Pasture-raised meat is often positioned as a more premium form of beef too, as the cattle used to produce it are said to roam and grow ‘freely’ in an outdoor environment. But while mass-produced beef is obviously no better when it comes to the planet or ethics, the authors believe their research could shift how government programmes (including funding and policy) incentivise beef production systems.

Currently, government subsidies heavily favour meat production – in the EU and the US, livestock farmers receive 1,200 and 8,000 times more funding than alternative protein companies, respectively. In the former, cattle farmers received half of their income through direct subsidies. The study’s authors also argue that it “provides important insights for agricultural stakeholders globally, such as in Brazil where pasture expansion is a leading driver of forest loss”.

They add that this will influence consumer choice as well, especially given the way beef is being increasingly marketed as a climate-friendly product. Companies like Tyson Foods in the US and supermarkets such as Sainsbury’s in the UK have both unveiled such products this year. But according to the latter’s life-cycle assessment, its ‘reduced-carbon’ beef (with 25% less CO2 emissions) will still have 74kg of CO2e of total GHG emissions, comfortably higher than dark chocolate’s 47kg of CO2e, as mentioned above.

The authors say that future research could integrate “more spatially explicit estimates of soil carbon sequestration and carbon stocks” and calculate carbon opportunity costs “based on how different cropland and grazing land is used”. “It could also incorporate additional types of environmental impacts and resource use, such as water use or eutrophication potential, which are important in assessing the overall sustainability of production systems,” the study states.

The researchers suggest further analysis into land use intensity and its relationship with GHG emissions, as well as an incorporation of different measurement approaches for gases, as each has its own lifespan – this includes metrics like GWP100, GWP20 and GWP*. The latter is being promoted as a tool to calculate methane emissions by the livestock industry around the world, but it presents a partial picture and significantly understates the actual environmental impact of meat.

“We have seen that many decision-makers defer to the global scientific institutions, such as UNFCCC, for guidance. For this reason, we also see an attempt from those industry groups to lobby at that level, and to create a body of scientific research that would make the case for this new metric,” Nusa Urbancic, CEO of corporate sustainability watchdog Changing Markets Foundation, told Green Queen last month.

She added: “These are distractions that decision-makers should resist. One thing is crystal clear: we need to rapidly cut methane emissions this decade and metrics that we adopt must reflect this climate emergency.”