Ocean Park Dreams: How The Hong Kong Tourist Attraction Fuels The Taiji Trade Supplying China’s Dolphinariums

7 Mins Read

Between September and March every year, fishermen in the Japan’s small coastal town of Taiji go on a gruesome hunt for dolphins. Famously depicted in the documentary film The Cove, the so-called Taiji dolphin hunters lure pods of dolphins are into a small cove, which is then netted off, trapping the animals. Then the real blood bath begins.

Some of the animals are brutally slaughtered with knives for their meat, turning the waters crimson in colour – a horrifyingly vivid image that has by now made the rounds across international media. Often this process also involves separating babies and mothers, which is very traumatic for dolphins given that they are highly social creatures.

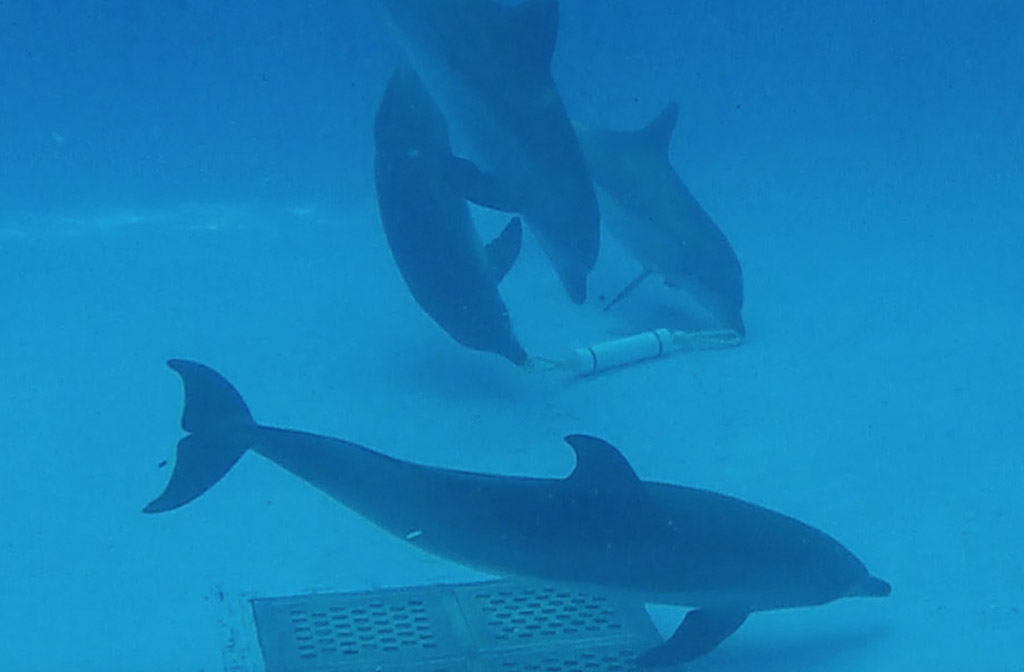

But what is less known is that a large percentage of the animals are kept alive to be sold off into a lucrative trade, the supply and sale of cetaceans to aquariums and marine parks across China and the world. Dolphin trainers come down to the cove to select the ‘beautiful’ dolphins, capturing them and effectively sentencing them to a life of captivity.

At the heart of this bloody trade is Ocean Park, one of the prized gems of Hong Kong’s long list of tourist attractions, where mainland visitors watch dolphin shows at the rate of millions per year, creating a growing demand for mainland China-based dolphinariums run by owners looking to capitalise on the popular yet cruel entertainment past time.

‘The money is in supplying dolphins for captivity’

In 2009, Taiji made international headlines when the Oscar-winning documentary The Cove exposed the brutal dolphin drive hunt that takes place every year in the small Japanese fishing village. Dolphins and other small cetaceans are driven into a bay, and they are either slaughtered on the spot for meat or captured to sell to dolphinariums.

At the time, much of the international concern centred on the inhumane drive hunting method used, with many taking aim at the cruel slaughtering methods to obtain cetacean meat for human consumption.

But it isn’t dolphin meat that is keeping the Taiji dolphin drive hunts going. Selling them to dolphinariums and marine parks – primarily to those in China – is what fuels the hunters, and for one simple reason: money.

“The money is in supplying dolphins for captivity in dolphinariums. Taiji [dolphin hunters] capture them, put them into pens and sometimes even train them to sell off for a higher price,” says Gary Stokes, founder and director of ocean conservation charity OceansAsia, in an exclusive conversation with Green Queen.

While documentaries like The Cove may have given viewers the impression that dolphin meat is a valuable commodity, in reality the market for it is very small and localised, according to Stokes.

“Dolphin meat is sold locally in Japan, but the price per kilogram is low compared to where the main profit is at – captive dolphins. Without the demand for captive dolphins, there wouldn’t be enough money to justify these drive hunts,” he adds.

Taiji dolphin hunters rake in huge amounts of cash for trained live dolphins. In the latest six-month period ending March 2020 when Taiji drive hunts took place, the Dolphin Project estimates that over 180 were taken captive. According to the International Marine Mammal Project, each dolphin can be sold for as high a price as US$150,000, more in some cases. Dolphin meat, on the other hand, brings in a mere US$500 on average.

China is driving the demand

The Taiji dolphin hunters operate within a curious regional regulatory loophole. In Japan, it is illegal to sell dolphins in captivity. In China it is illegal to do so domestically but dolphinariums are allowed to import the animals. With no domestic market, the Japanese hunters are more than happy to supply mainland China.

In 2015, the Japanese Association of Zoos and Aquariums took the decision to no longer support Taiji hunts, effectively ending the hunters’ domestic demand. Across the globe, animal rights activists have secured victories against dolphinariums in many countries. It’s a different story in China.

Recent reports from Reuters found that China currently has more than 60 marine parks, and is building on average a new aquarium every single month. There are already more than 36 large-scale aquarium and marine park projects slated to open by 2021.

Every new aquarium in China needs animals, and with the national Law on the Conservation of Wild Animals having banned the domestic dolphin trade since 1988, the dolphins are almost exclusively sourced from Taiji. According to data from Japan’s Finance Ministry, of the 728 officially recorded live dolphins for export between 2010 and 2018, 68% were sold to China.

“Taiji captures all of them, Chinese marine park then buy them for their own theme parks as well as acting like a launderer too,” Stokes telss Green Queen. “No one wants to buy them from Taiji ever since the film The Cove exposed the cruelty, so other countries who want captive dolphins then buy them from the dolphinariums in China who got them from Taiji in the first place.”

Hong Kong’s Ocean Park is the inspiration

Stokes added that for many Chinese dolphinarium owners, Hong Kong’s original marine theme park, Ocean Park, serves as the ultimate inspiration of success. Mainland tourists account for nearly half of Ocean Park’s total yearly visitors, making it the ideal role model destination for domestic entrepreneurs to dive into the lucrative industry, believing that there is big business to pursue.

“It was because of Ocean Park that everyone in China wanted to have a dolphinarium,” says the OceansAsia founder.

What’s more, current Ocean Park-owned dolphins are mostly descended from dolphins captured in Taiji drive hunts. While Ocean Park’s official website states that 30% of its initial dolphin population was imported from wild populations in Indonesia between 1987 and 1997, no additional information is offered to account for the remaining 70%.

“Most of the Ocean Park dolphins came from Taiji originally,” underlines Stokes. “Then they bred them in their own facilities, and soon they had enough in their gene pool to continue breeding them and didn’t need to source them from Taiji anymore.”

Ocean Park bailout hints at exploitation continuation

Despite years of economic downturn and further fallout from 3 months of shuttered doors due to the coronavirus pandemic, last month the Hong Kong government approved Ocean Park’s request for an astonishing HK$5.4 billion (US$697 million) bailout.

This came on the heels of strong opposition from lawmakers across all parties in Hong Kong’s legislature, and effectively shutting down the hopes of animal welfare activists and conservationists who have long called for an end to the theme park’s inhumane marine captivity and breeding programmes.

While the park announced earlier in January that it would close its exploitative dolphin and sea lion show and replace it with 26 new amusement rides, there have yet to be any concrete plans to retire dolphins and eliminate artificial breeding once and for all.

According to Stokes, there was a buy-in from certain Ocean Park stakeholders to pull the curtain on dolphin shows once and for all, but others were not so bought in.

“We suggested a two-tier strategy before to shut own the show and stop the breeding program so that they enter a wind down phase, then step two would be to set up a sea pen somewhere in SE Asia to retire dolphins too,” explains Stokes. “In fact, the scientific community of Ocean Park were fully supportive of it, but we needed to convince the board of directors.”

Without a permanent end to marine captivity in Ocean Park, the outlook for stopping Taiji’s dolphin drive hunts appears grim. Animal husbandry for marine mammals in captivity is very poor in marine parks in mainland China, and as such when the animals get sick and die they are quickly replaced with new animals from Taiji. Let’s not forget that the mainland demand all began with the popularity of Ocean Park in the first place.

Lead image courtesy of Unsplash.