Oatly Calls for Mandatory Carbon Labelling, Offers ‘Big Dairy’ Free Ad Space to Publish Climate Footprint

8 Mins Read

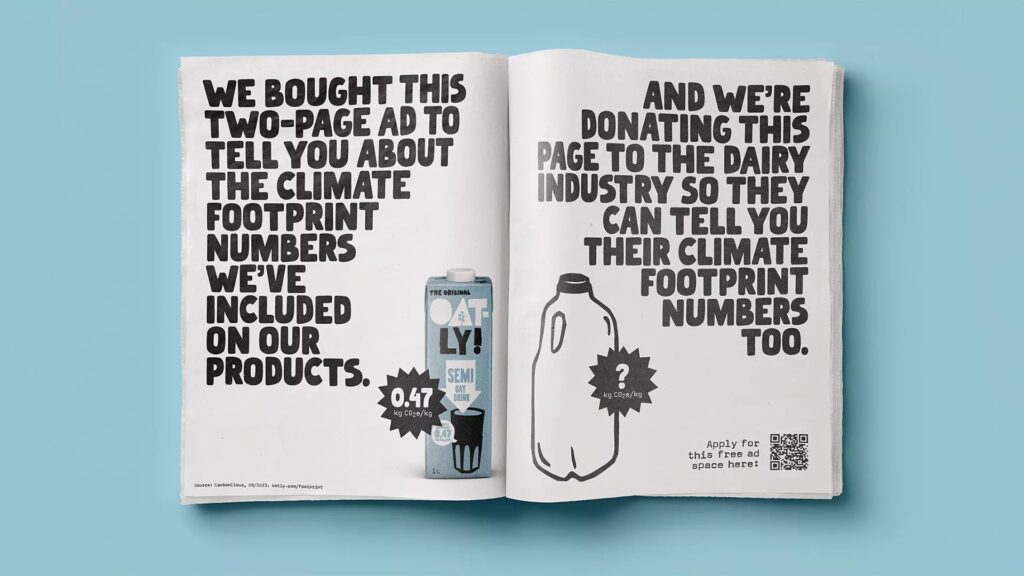

Oatly is calling on the UK food and drink industry to adopt mandatory carbon labelling on product packaging with a new campaign. As part of this effort, it is offering free ad space to dairy producers, challenging them to publish their climate footprint alongside ads displaying Oatly’s footprint.

Oatly is campaigning for mandatory carbon footprint labelling for food and beverage products in the UK, pushing for increased transparency to allow consumers to make more informed choices. As part of the initiative, it’s challenging dairy companies to disclose their climate footprints, with a view to providing clearer and more accurate comparisons to the public.

To do so, the Swedish oat milk giant is offering free high-profile ad spaces via billboards in London and Manchester across billboards, as well as print and radio commercials.

“We bought this billboard to tell you about the climate footprint numbers we’ve included on our products,” the posters read, referring to Oatly’s printing of its products’ carbon footprint in the UK since 2019. “And we’re donating this one to the dairy industry so they can tell you their climate footprint numbers too,” reads an adjacent billboard.

While the campaign is UK-focused, Oatly is offering one spot on a Berlin billboard too.

How dairy compares to plant-based milk

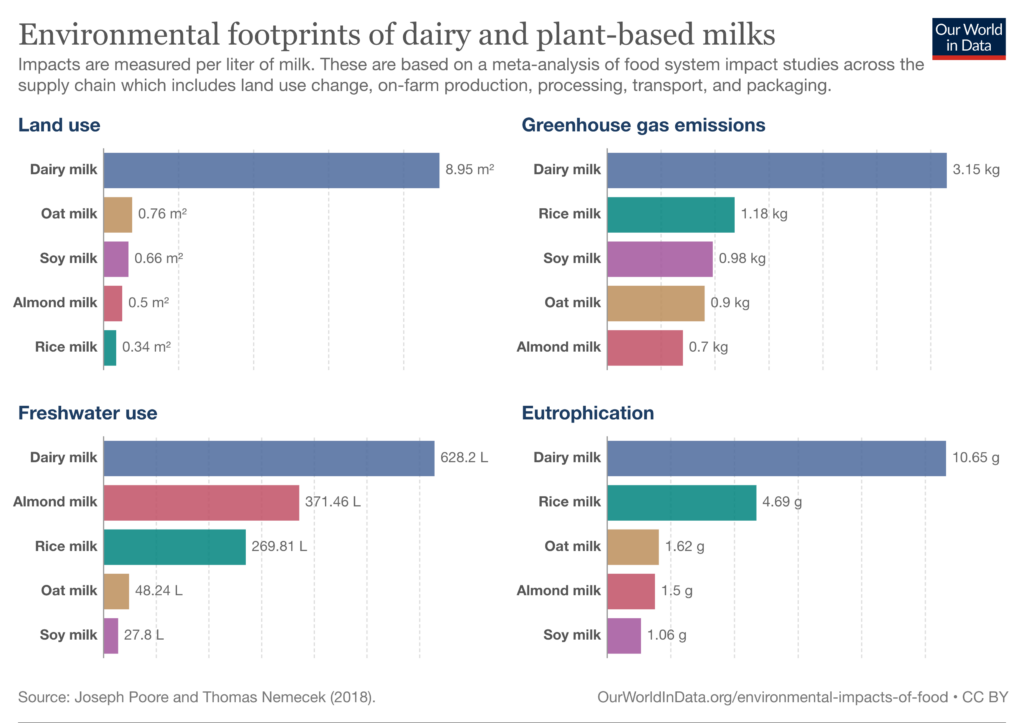

The dairy industry is notorious for its high environmental footprint, water use and land use. A landmark study by scientists at Oxford University in 2018 found that, on average, cow’s milk uses 8.95 sq m of land per litre – over 11 times higher than the next on the list, which is oat milk (at 0.76 sq m). This is followed by soy (0.66 sq m), almond (0.5 sq m) and rice milk (0.34 sq m).

In addition, the research revealed that conventional dairy uses 628 litres of water for a litre of milk – almond milk, at 371.5 litres, is next, with rice milk raking up 269.8 litres, oat milk using 48.2 litres, and soy milk just 27.8 litres (22 times lower than cow’s milk). In terms of GHG emissions, dairy represents 3.15kg of CO2e per litre, which is nearly three times as much as rice (1.18kg). In contrast, soy milk emits 0.98kg, oat milk amounts to 0.9kg, and almond milk 0.7kg per litre.

Oatly, which uses climate intelligence platform CarbonCloud (a fellow Swedish company) to measure its product emissions from farm to store, claims its products emit as little as 0.43kg of CO2e per litre, with its Light Oat Drink coming top of the list. But the highest amount emitted by its milk alternatives is the half-litre Barista version, which amounts to 0.64kg of CO2e per litre – still nearly five times lower than the Oxford study’s estimates for dairy.

Extending its partnership, it’s offering a 50% discount code for CarbonCloud’s services to businesses that haven’t yet calculated their emissions, as part of its climate labelling campaign. Other food-focused carbon calculators include UK-based My Emissions and Californian company Planet FWD’s new AI platform.

Oatly’s ‘grey paper’

To help make carbon labelling mandatory, Oatly has published a ‘Grey Paper’, referring to how “climate labelling isn’t a black and white issue, where certain foods are good and others are not”. The paper makes three key arguments to advocate for the cause.

The first builds upon scientific consensus about the food industry’s emissions. A third of all global emissions come from this sector, while livestock farming produces between 11-19.5% of the planet’s overall emissions. Further studies have shown that animal-derived foods like meat and dairy cause twice as many emissions as plant-based foods, and replacing half our meat and dairy consumption with plant-based alternatives can double climate benefits.

Oatly’s second pillar highlights how consumers already receive such information in other sectors. People look at Energy Performance Certificate ratings when buying houses, emissions data when purchasing cars, and Energy Rating data when buying electronic appliances. Oatly argues that the same logic should be applied to food and drink too.

The final argument relies upon public support for mandatory carbon labelling. Oatly conducted a consumer poll of 2,000 UK adults, with 62% expressing support for a policy-making the act mandatory. Additionally, 55% believe companies should be obligated to disclose this data, with the figure rising to 78% for under-35s. Meanwhile, 59% of Brits said they’d reduce or completely eliminate products with high carbon footprints from their diets if they were given accurate emissions data.

Consumers can see through greenwashing

In 2020, similar research by Carbon Trust showed that 63% of consumers in the UK felt carbon labelling was a good idea, while 63% would feel more positive about a product that had reduced emissions. However, only 35% said it was important for them to know a company is taking action on its environmental impact before purchasing its products, while 51% said they don’t think about carbon footprints when buying products.

More recent data from last year revealed that 73% of Brits felt it was important for food and drink to have low carbon footprints, while 49% wanted to see carbon footprint labelling on products. But only 25% claimed to fully understand the meaning of the term ‘carbon-neutral’.

Earlier this year, accounting firm KPMG found that 54% of Brits said they’d stop buying from a company that has misleading claims about the sustainability of its products. Moreover, 45% have heard of the term ‘greenwashing‘, and 76% said false or misleading claims are the clearest examples of greenwashing.

This is part of what is driving Oatly’s campaign: transparency and accountability to help the public make greener decisions. “This is about giving consumers the freedom to make informed choices about what they’re buying and how it impacts the planet – from grower to grocer,” says its UK general manager Bryan Carroll.

And that’s not to say Oatly’s record is squeaky clean. In January 2022, the oat milk producer was at the receiving end of an ad ban by the UK’s Advertising Standards Authority (ASA), which accused it of greenwashing consumers with unsubstantiated environmental claims in its comparison of oat milk with conventional dairy.

For instance, one commercial – with the tagline “Need help talking to dad about milk?” – stated that Oatly generates 73% fewer carbon emissions than milk. The comparison was between Oatly Barista and full-cream milk, but the ASA said consumers would understand it to mean all of Oatly’s products. And in two newspaper ads, it stated that over a quarter of global emissions come from the food industry, with meat and dairy accounting for half of that. The ASA said Oatly included fish and eggs as part of meat and dairy, but people may assume it has a narrower definition.

And it’s not just the UK – the brand was hit by three lawsuits in New York after being accused of greenwashing by its investors in 2021. Oatly did introduce its carbon footprint labels in the US earlier this year, with a similar campaign to push for mandatory labelling.

Greenwashing legislation is key

This is why policy intervention is key. The UK’s new Green Claims Code lays out a six-point checklist to help businesses make credible environmental claims. And in 2021, British startup Provenance launched its Provenance Framework, an open-source rulebook listing the criteria companies need to fulfil to make a true environmental claim, and avoid greenwashing and misleading consumers.

The EU, meanwhile, finalised a new law to curb greenwashing last month, banning terms like ‘carbon-neutral’ and ‘eco-friendly’ from product labels, unless businesses can provide “proof of recognised excellent environmental performance relevant to the claim”. One of its proposed sister laws, the Green Claims Directive, mandates businesses to assess and meet new minimum “substantiation requirements” for sustainability claims – but progress on this has stagnated.

Carroll says it is unreasonable to expect emissions cuts and consumer behavioural changes without providing people with the information they need: “Given the urgency of our climate challenge, we believe it should be as easy for shoppers to find the climate impact of what they’re buying, as it is to find its price tag.”

In this vein, Oatly is hosting a Reddit AMA (Ask Me Anything) session this Friday, where its sustainability director Caroline Reid will discuss and field questions about climate labels. The brand has put out a call for an executive from the dairy industry to co-host the event.

Oatly’s tough turn

The oat milk giant has had a difficult couple of years, with post-pandemic supply chain issues and the cost-of-living crisis hitting its stock hard, which has crashed by as much as 94% since its US IPO in 2021, when it was worth $10B. This was exacerbated by leadership changes – with former CEO Toni Petersson moving into a co-chair role – and restructuring, as it reduced headcount by 25% across Europe, the Middle East, and Africa.

In November 2021, it saw a 20% fall in shares directly due to a warning about its products’ quality, as well as delivery delays, while five of its products were voluntarily recalled in August 2022 due to safety issues. It also withdrew its ice cream tubs from UK supermarket shelves as it faced increased competition, while its market share dwindled in Asia due to “a slower-than-expected post-Covid-19 recovery in China”. It led the company to eliminate SKUs and slow down on product expansion.

Now, as Oatly aims to reduce its products’ climate footprint by a further 70%, can Oatly turn a financial corner as well as help bring about labelling legislation? Its aim is to work with stakeholders over the next few months to exert influence on policymakers to introduce a mandatory carbon labelling system – “one that doesn’t cost the earth but helps preserve the Earth”.

“Together, we can put collective pressure on the UK government to make this happen and not get watered down like some other environmental policies have, sadly, been lately,” says Carroll, in a not-so-subtle reference to UK Prime Minister Rishi Sunak’s U-turn on the country’s climate commitments.