How An Ancient Mould Can Turn Food Waste Into Michelin-Starred Dishes

7 Mins Read

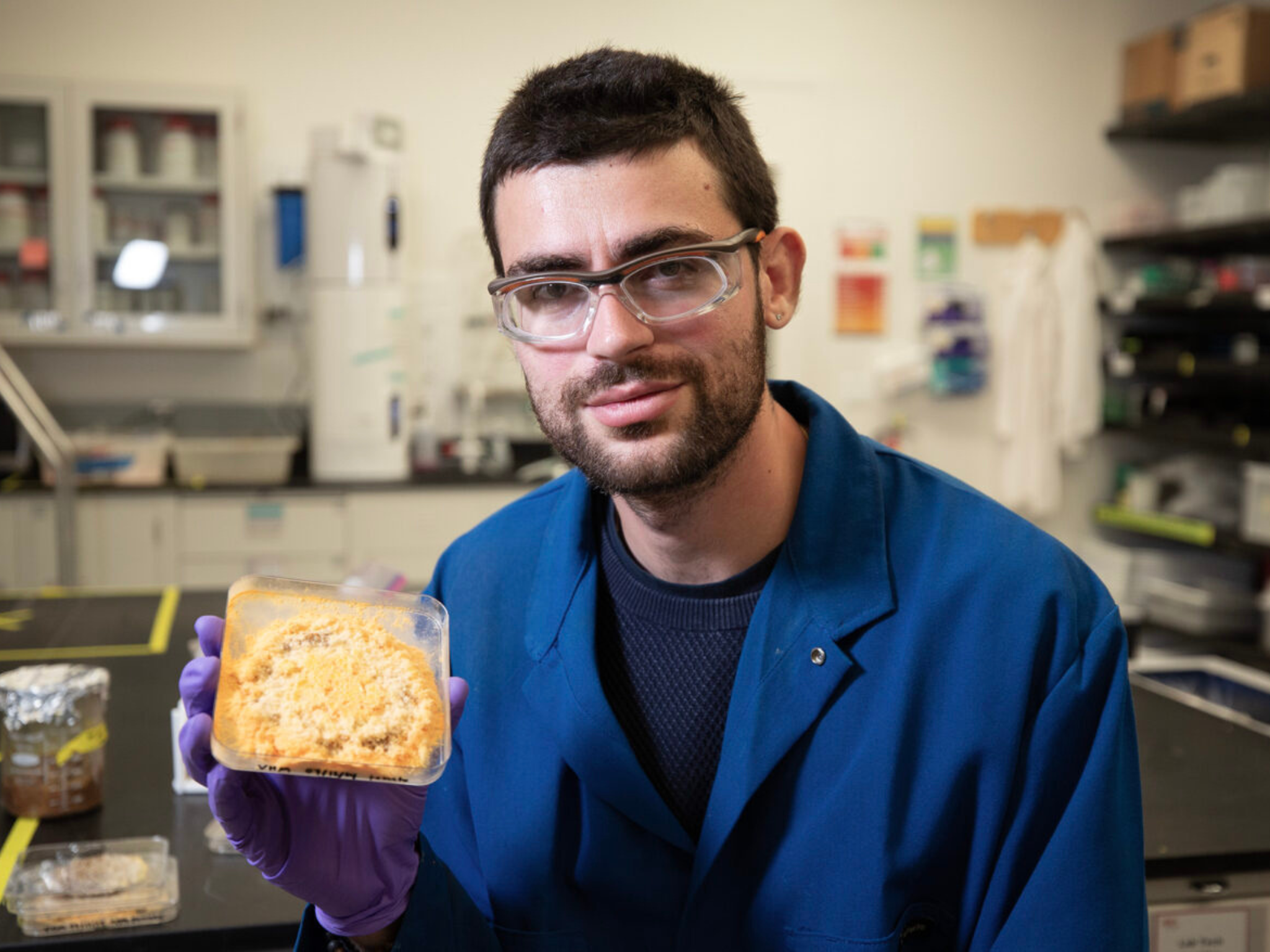

Researchers at UC Berkeley are betting on fungi strain Neurospora intermedia to turn food destined for the bins into haute cuisine.

Who knew mould could be the secret to saving food waste?

In a new research paper, that’s what scientists at UC Berkeley are proposing, arguing that food waste could be turned into gourmet meals fit for Michelin-starred restaurants through the use of fungi.

In Copenhagen, for example, two-starred eatery Alchemist has been serving up orange mould grown on rice as a dessert, while at New York restaurant Blue Hill at Stone Barns (which also has two Michelin stars), you might soon order a burger made from mould grown on oat milk pulp, or a piece of mouldy bread that taste like a grilled cheese sandwich when fried.

The mould in question is Neurospora intermedia, a multicellular fungi strain used for centuries in Indonesia to make oncom, a fermented plant protein derived from okara (the pulp leftover from soy milk production). The researchers are betting on its proven status as a staple food to highlight its potential to curb food waste in the West.

A third of all food is lost or wasted globally, resulting in up to 10% of global emissions – that’s five times higher than the entire aviation industry. “It isn’t just eggshells in your trash. It’s on an industrial scale,” said research lead Vayu Hill-Maini.

“What happens to all the grain that was involved in the brewing process, all the oats that didn’t make it into the oat milk, the soybeans that didn’t make it into the soy milk? It’s thrown out.”

A chef-turned-chemist, Hill-Maini has been collaborating with Blue Hill for the last two years to grow the fungus on grains and pulses. He has also been part of a research effort transforming koji mould into better-tasting meat analogues.

From fungus to food in a day and a half

Hill-Maini was introduced to oncom by a fellow chef from Indonesia. “This food is a beautiful example of how we can take waste, ferment it and make human food from it,” he recalled thinking. “So let’s learn from this example, study this process in detail, and maybe there [are] broader lessons we can draw about how to tackle the general challenge of food waste.”

In West Java, there are two kinds of oncom. The red-coloured one is made from fermenting okara, and the black oncom is grown on the leftovers from peanut oil pressing. What caught Hill-Maini’s attention was that the fungi can transform indigestible plant material – such as pectin and cellulose – into digestible and nutritious food in under two days.

He found that the fungus in red oncom is primarily Neurospora intermedia. “What was very clear is, wow, this fungus is probably dominant and maybe sufficient for making this food possible, growing on the cellulose-rich soy milk waste and making the food in 36 hours,” he said.

“The fungus readily eats those things and in doing so makes this food and also more of itself, which increases the protein content. So you actually have a transformation in the nutritional value. You see a change in the flavour profile. Some of the off-flavours that are associated with soybeans disappear. And finally, some beneficial metabolites are produced in high amounts.”

That said, it’s not just soy or oat milk pulp that this fungus can transform. The research revealed that Neurospora intermedia can grow on 30 different agricultural sidestreams without producing any toxins (which can accumulate in certain mushrooms and moulds).

These byproducts include sugarcane pulp, tomato pomace, coffee grounds, almond skins and hulls, pineapple cores, banana peels, brewers’ spent grain, and wheat bran – though the level of growth on each waste product varies.

Chefs – and patrons – impressed by Neurospora

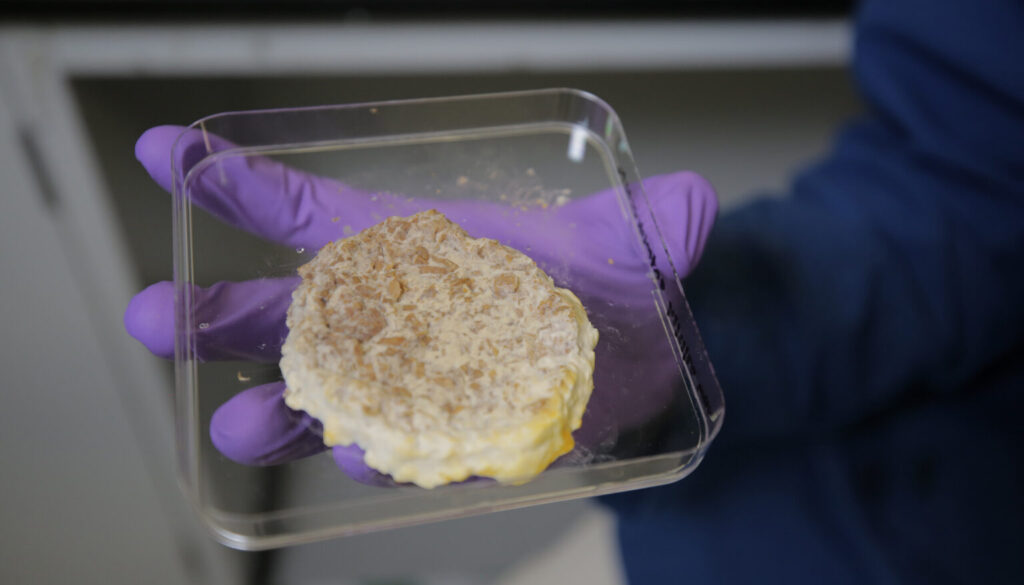

Hill-Maini’s exploits inspired Blue Hill to install an incubator and tissue culture hood in its test kitchen this summer. this will enable the eatery to put more focus on fungal foods. Andrew Luzmore, chef in charge of special projects at Blue Hill, has tested many Neurospora experiments, but said his favourite is made from stale rice bread.

“The most important thing – especially for me as a chef – is: ‘Is it tasty?'” said Hill-Maini. “If it doesn’t have sensory appeal, if people don’t perceive it positively outside of a very specific cultural context, then it might be a dead end.”

He collaborated with Alchemist co-owner and head chef Rasmus Munk to present red oncom to 60 people who had never tried it before. “We found that, basically people who never tried this food before assigned it positive attributes – it was more earthy, nutty, mushroomy,” he recalled. “It consistently rated above six out of nine.”

The team at Alchemist also grew the mould on peanuts, cashews and pine nuts, which too received positive feedback. Different substrates impart their own flavours – rice hulls or apple pomace lend fruity notes to the Nuerospora. “Its flavour is not polarising and intense like blue cheese. It’s a milder, savoury kind of umami earthiness,” explained Hill-Maini.

Underlining this potential, Munk added a Neurospora dessert to the menu: it’s a plum wine jelly topped with unsweetened rice custard that’s inoculated with the mould and left to ferment for 60 hours. Served cold, it’s topped with a lime syrup made from roasted leftover live peel.

When grown on starchy rice, the fungus secretes an enzyme that liquifies the rice and makes it intensely sweet. “We experienced that the process changed the aromas and flavours in quite a dramatic way — adding sweet, fruity aromas,” Munk said.

“I found it mind-blowing to suddenly discover flavours like banana and pickled fruit without adding anything besides the fungi itself. Initially, we were thinking of creating a savoury dish, but the results made us decide to instead serve it as a dessert,” he added.

Solving food waste through fermentation

We’ve been fermenting food for millennia, but the technique has taken on increased interest from companies who are using it in novel ways and consumer looking for products that are better for their tastebuds, better for the climate, and/or better for their guts.

The enthusiasm can be encapsulated by the hike in investor appeal – fermentation-derived food startups have surpassed the total capital they raised in 2023 within the first half of this year. In the latter period, the segment made up 57% of the total investment in the alternative protein sector.

“In the last few years, I think, fungi and moulds have caught the public eye for their health and environmental benefits, but a lot less is known about the molecular processes that these fungi carry out to transform ingredients into food. Our discovery, I think, opens our eyes to these possibilities and unlocks further the potential of these fungi for planetary health and planetary sustainability,” said Hill-Maini.

“This is a new tool in the chef’s toolbox,” he added. “It’s a new way of cooking, a new way of looking at food that hopefully makes it into solutions that could be relevant for the world.”

Hill-Maini hopes to discover just how Neurospora produces the flavours and aromas it does, while continuing his efforts to take food out of the waste stream.

“The reason why we have loved working with Vayu is because he embodies so much of where we are going as an organisation,” said Blue Hill’s Luzmore. He added that the restaurant is evolving into “a new type of research centre that treats the study of food and farming as one subject”, with an innovation sandbox in the works.

Similarly, at Alchemist, Munk has opened a food innovation centre called Spora, which is initially focusing on upcycling food industry sidestreams and creating diverse protein sources.

“We have said from the start that Alchemist’s ambition is to change the world through gastronomy, and this project has that kind of potential. I am very excited to see what other culinary applications this research can lead to in the future and using other waste products from the food industry,” Munk said.

According to climate non-profit Project Drawdown, reducing food waste is the top climate solution to reduce emissions in line for a 2°C future – the hopes of keeping temperature rises to 1.5°C are slimming by the day. Estimates also suggest that we could feed a quarter of the world’s population (two billion people) with all the food that’s wasted and lost.