Mission Barns Upends the Production Status Quo with Novel, Scalable Bioreactors for Cultivated Pork Fat

5 Mins Read

California’s Mission Barns has developed a novel bioreactor that is easy to scale and can lower the cost of cultivated meat, with regulatory approval imminent ahead of its planned market launch.

Moving away from the conventional single-cell suspension reactors of the biopharma sector, Mission Barns is hoping to solve cultivated meat’s scalability and cost problems with a novel solution.

The Californian startup is working on a cultivated pork fat called Mission Fat, which is meant to be mixed with plant-based proteins and ingredients to make hybrid meat products like bacon, pepperoni and chorizo.

Founded in 2018 by Eat Just alum Eitan Fischer, Mission Barns plans to launch these products in both foodservice and retail channels once it receives regulatory approval, for which it has filed dossiers in several countries. But to meet the market demand for cultivated meat, the company (and the industry) needs to solve two major bottlenecks: production capacity and price.

To get there, the startup has eschewed conventional bioreactors to develop a novel machine that’s more efficient, easier to scale, and ends up with a cheaper final product.

“We have different sizes of our proprietary bioreactors, ranging from R&D-scale units for experiments and optimisation, to our largest scale which is currently at pilot scale,” explains Bianca Lê, technical affairs and growth principal at Mission Barns.

The problem with using pharmaceutical bioreactors for cultivated meat

For Mission Barns, the need for a better bioreactor solution stemmed from the fact that a lot of the biotechnology used to make biopharmaceuticals isn’t purpose-built for cultivated meat.

There are inherent differences between the two: the per-tonne demand for cultivated meat is seven times higher than for biopharma drugs produced from mammalian cell cultures; the accepted ideal costs for the former is around $5-10 per kg, versus $500,000-1M for the latter; and people have more concerns about GMOs in food than in medicines.

“Bioreactors are vessels designed to grow cells. They’ve historically been designed to produce products for the biopharmaceutical industry,” Lê tells Green Queen. “We’ve invented a novel bioreactor that allows us to scale the production of cultivated meat, whether it’s pork, beef, or chicken, or fat or muscle.”

Most cultivated meat producers use bioreactors that support single-cell suspension, as these are readily available at larger scales. But to produce cell cultures this way, companies need to genetically modify anchorage-dependant cells (those that need something to attach to) so they can grow in suspension liquids.

“Meat is made up of muscle and fat cells embedded within a protein scaffold that provides structure and texture,” explains Lê. “These anchorage-dependent cells are called ‘adherent cells’ because they need to attach (or adhere) to this scaffold in order to grow. This is in contrast to cells that are able to freely float and grow whilst suspended in liquid (called ‘suspension cells’).”

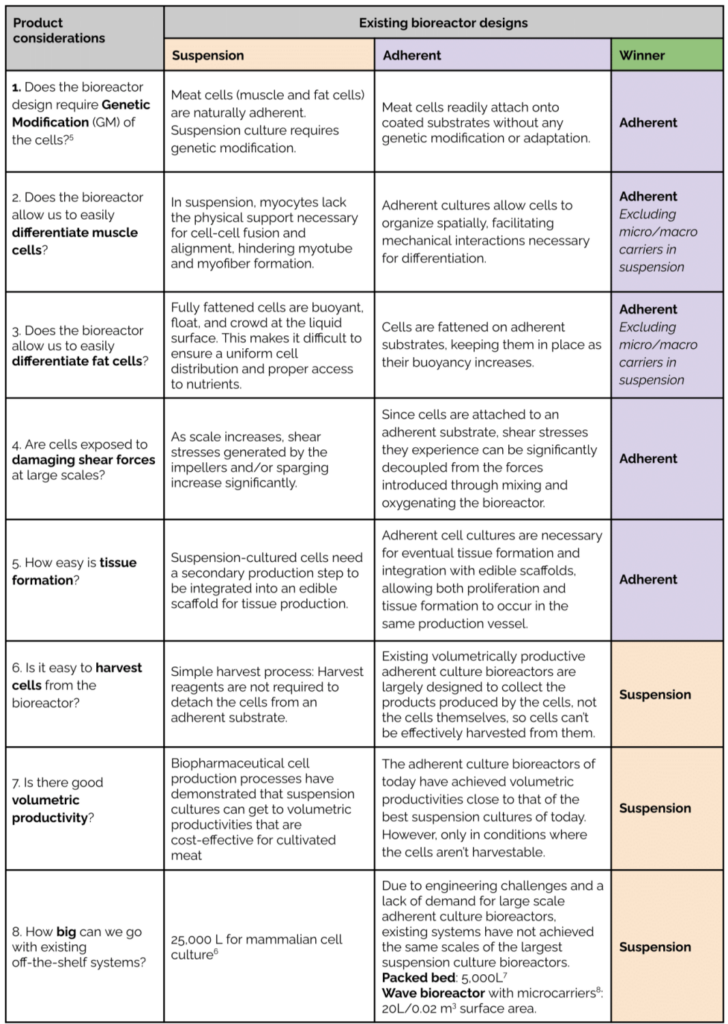

Mission Barnes argues that existing suspension culture bioreactors aren’t effective in making non-GM cultivated muscle or fat, while commercially available adherent culture bioreactors only exist at small to medium scales due to a lack of market demand.

“Rather than changing the meat cells to suit a suspension culture bioreactor, our bioreactor recreates the same adherent growth conditions inside an animal’s body,” says Lê.

The mission behind the novel bioreactors

For the new bioreactors, Mission Barns wanted to meet four key design specifications that outperform current options (whether suspension or adherent), with the aim of achieving high production capacities at low costs.

First, the company wanted to “efficiently grow and harvest meat cells (which are anchorage-dependent) from any species, using less space than existing harvestable adherent bioreactors”, outlines Lê. Then, it aimed to bypass the lengthy development process required for new cell lines to adapt to existing bioreactor environments.

The new machine also needed to be able to easily “mature muscle and fat cells, taking into account changes in geometry, density, and buoyancy”. And finally, the startup wanted the bioreactors to “produce whole-cut tissue products within a single vessel, eliminating the need for separate tissue production equipment”.

“We have successfully developed a bioreactor that meets these specifications, allowing us to cultivate both muscle and fat cells, or tissue, from any species,” says Lê.

“Our innovative adherent approach enables us to focus on engineering a single system – the bioreactor – instead of having to modify and adapt different cell types to work with existing bioreactors like suspension bioreactors. This makes the process more efficient and straightforward.”

Mission Barnes has additionally developed fully chemically defined and animal-free culture media, non-GM pork cell lines that can differentiate fat and proliferate quickly, and food-grade, cheap process reagents and substrates for coating, washing, and harvesting.

With partners lined up, Mission Barns expects US approval soon

“At this pre-market stage, our primary focus is on bioprocess optimisation,” says Lê. The startup’s bioreactor is already in its third iteration, which is over 500 times larger than the initial prototypes.

Now, it is planning a larger-scale manufacturing facility. “Our current plan involves having bioreactors with working volumes in the tens of thousands of litres at commercial scale, when we’ll be outputting tens of millions of pounds of final product per year,” she adds.

Mission Barns, which has so far raised $60M, conducted a techno-economic analysis of this future facility, finding that with continued tech advancements – such as efficient media use, innovative scale-up, and an optimised supply chain for raw materials – it could reduce costs to reach price parity with conventional pork.

Asked about the regulatory progress, Lê reveals that Mission Barns is “actively working with regulators around the world” to bring its products to market “in a way that can assure consumers of its safety and high quality standards”.

“We’ve already completed a comprehensive safety assessment of our cultivated pork, and expect the agencies to publicly agree with our assessment soon, including the US,” she says.

The current pilot plant facility “can produce enough product to supply a handful of restaurants and retailers”. This would help with the initial market launch, as Lê points out: “We have a number of exciting partnerships confirmed with major US grocery stores, restaurants and food distributors who we have partnered with to sell our products.”