How Microplastics Damage the Gut Microbiome & Raise the Risk of Chronic Diseases

4 Mins Read

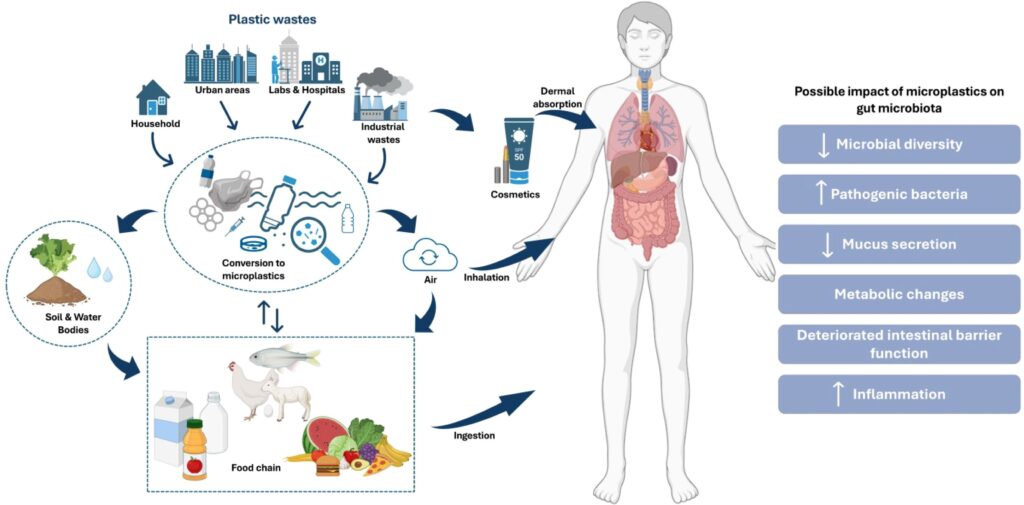

Researchers in India highlight how microplastics harm the human gut microbiome, and subsequently our overall health.

From takeaway coffee cups and washing machines to sea salt and tap water, microplastics are omnipresent in the environment. And they’re a threat not just to the Earth and its oceans, but also its inhabitants.

These are plastic particles smaller than 5mm that emerge as breakdown products of larger plastics. They’re primarily composed of polymers – including polyethylene and polystyrene – and absorb armful environmental chemicals like pollutants and heavy metals.

There are 14 million tonnes of microplastics on the ocean floor and 24 trillion pieces of microplastic on the ocean surface, damaging water bodies and affecting the survival, growth and fertility of aquatic life. But these particles have also been discovered in the human body, which they enter mainly through food and beverages, as well as inhalation.

One study suggests that 97% of children and teenagers have plastid and microplastic debris in their bodies. These are linked to a host of diseases and health issues, from gastrointestinal disorders and systemic inflammation to antimicrobial resistance and chronic conditions.

But a new study by Indian researchers focuses on their impact on the gut microbiome, which is becoming more and more important in consumer health discourse, thanks to the rise of GLP-1 agonist drugs, documentaries like Netflix’s Hack Your Health, and personalised nutrition apps like Zoe.

The dangers of microbial imbalances in the gut

The research, published in the Frontiers in Cellular and Infection Microbiology journal, outlines how microplastics are present in personal care items, paint, sewage sludge, car tyres, and more, but ingestion is their primary route inside the human body.

Fish and seafood are considered among the main sources of ingested microplastics, whose concentration in the ocean reaches up to 102,000 particles per cubic metre. Additionally, sea salt, table sugar, fruits and vegetables, and tap water allow microplastics into the body.

The study argues that these adversely affect our gut health, a key focus point for today’s food industry. Awareness about the gut has exploded since drugs like Ozempic and Wegovy came into the mainstream. These replicate the GLP-1 incretin hormone in the human gut, which can be regulated with dietary fibre and fermented foods, prompting manufacturers to come up with new innovations in line with the trend.

According to the researchers, the presence of microplastics in the gastrointestinal tract (where they remain for a long time due to their resistance to digestion) can lead to gut dysbiosis, a state of imbalance between beneficial and harmful bacteria.

Microbial dysbiosis can lead to many health impairments, like poorer gut function and immunity, and a greater risk of gastrointestinal disorders, obesity, cancer, inflammatory bowel disease, and autism.

This imbalance may also trigger inflammatory responses and increase gut permeability, causing a condition called leaky gut. It allows harmful substances such as including toxins, pathogens, and undigested food particles, to pass from the gut into the bloodstream.

This pathogen transfer can lead to autoimmune diseases, and the presence of microplastics further worsens leaky gut – their sharp edges cause microabrasions in the gut lining and disrupt the gut barrier’s integrity, while releasing harmful chemicals that lead to oxidative stress and inflammation.

Collaboration, education and dietary shifts key to fighting microplastics

Microplastics are a detriment to the different gut networks in the body, disrupting the axes with the liver, heart, kidneys, and brain.

In the gut-brain axis, for example, dysbiosis can cause neuroinflammation, leading to neurological and psychiatric conditions such as anxiety, depression, and cognitive decline. It can further reduce the production of short-chain fatty acids, which are crucial for brain health.

Microplastics were found to affect intestinal function too, trigger inflammatory responses and induce oxidative stress, which in turn impact liver function and overall metabolism.

“The altered microbiome compromises the gut’s critical role as a barrier and regulatory organ, setting the stage for systemic inflammation and chronic diseases that affect the entire body,” the study notes. “The pervasive presence of MPs in the environment and their ability to infiltrate the human body underscore the urgent need for further research to fully understand their health implications.”

To minimise the impact of microplastics on our health, researchers advocate for a multifaceted strategy. Governments and industries should collaborate to regulate plastic production, enhance waste management, and develop alternatives that are friendlier to people and the planet.

At a policy level, stricter regulations for plastic disposal and recycling are required, while microplastic levels in water, air and food need to be monitored. Lawmakers should also encourage innovations in filtration technologies, public education, and dietary shifts, such as support for plant-based and cultivated seafood.

Microplastic exposure can also be reduced by the minimal use of plastic packaging, avoiding single-use plastics, filtering drinking water, and improving air quality. “Standardised monitoring methods, better waste treatment technologies, and stricter controls on plastic production are essential steps forward,” the study suggests.

But in a blow to the authors’ recommendations, leaders across the world failed to agree to an international plastics treaty that would have legally required countries to curb plastic pollution, particularly in marine environments, after oil-producing states lobbied against the move during talks last month.