Two in Five People Support Rationing of Meat & Fuel to Fight Climate Change

5 Mins Read

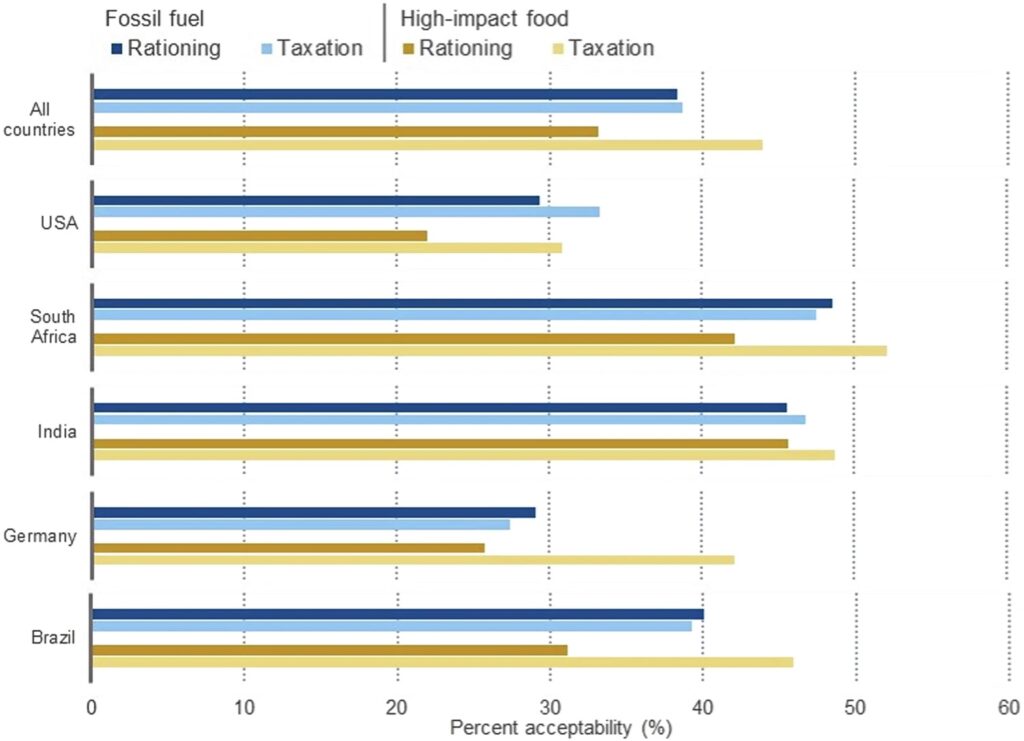

Around 40% of consumers back measures like rationing and taxing high-impact commodities like meat and fuel to address the climate crisis.

Over the years, a slew of studies have floated the idea of a carbon tax on things like fossil fuels and meat, two of the most highly polluting industries. These ideas – while crucial in a 1.5°C context – have proved to be controversial, receiving (obvious) backlash from Big Oil and Big Meat, as well as some policymakers and a certain set of consumers.

A new study, however, provides an alternative. What if we ration these foods? Could that be an effective policy instrument? According to the intercontinental survey – covering over 8,650 people in Brazil, Germany, South Africa, India, and the US – nearly two in five consumers think so.

“Rationing may seem dramatic, but so is climate change. This may explain why support is rather high,” said Oskar Lindgren, a PhD student at Uppsala University and lead author of the study.

Published in the Humanities & Social Sciences Communications journal, the research compared the acceptance of rationing fuel and “emission-intensive” food like meat with that of taxes on the same products, and found that the levels of support are on par with each other.

For example, 39% of people were in favour of fuel taxes, and 38% back rations. The gap with meat was larger, with a third of respondents embracing rations, and 44% saying yes to taxes (as Denmark has done).

“Most surprisingly, there is hardly any difference in acceptability between rationing and taxation of fossil fuels,” added Mikael Karlsson, a climate leadership lecturer at the university, and co-author of the study. “We expected rationing to be perceived more negatively because it directly limits people’s consumption.”

Support for rations and taxes varies based on economic status

The research found that the levels of acceptance fluctuated between countries, with low- and middle-income countries – i.e., those most impacted by the climate emergency – exhibiting greater support for rationing.

The US and Germany (the world’s first- and third-largest economies, respectively) were the least enthusiastic about these measures. When it comes to fuel rations, less than a third of people in either country are in favour, while nearly half (around 45%) are against. Likewise, a third of Americans and 27% of Germans support a fuel tax, versus 43% and 44% who don’t, respectively.

But 49% of South Africans and 45% of Indians back a fuel ration, with opposition rates below a quarter. Brazil seems more split, with 40% for and 31% against the rationing of fossil fuels.

The acceptance gap between rations and taxes broadens with food. For example, 22% of Americans, 26% of Germans and 31% of Brazilians support a meat ration, but 55%, 52% and 42% are against it. But the number of people who back such policies is higher than those who oppose them in South Africa (42% vs 31%) and India (46% vs 25%).

Taxes on foods like meat, however, seem to be the most popular among consumers. At 52% acceptance, South Africa leads the way (vs 24% against), followed by India (49%), Brazil (46%), and Germany (42%). The US is the least supportive of meat taxes, with only 31% in favour, and 43% opposed to them.

“Respondents in India and South Africa are more exposed to resource scarcity, fostering an openness to accept policies designed to manage scarce resources, like rationing,” the study reads.

“On the contrary, the large proportion of respondents in Germany and the US expressing strong dismissive attitudes towards both types of rationing suggests that the instrument, if proposed, could face significant opposition in high-income countries where individuals in general are less accustomed to resource scarcity.”

Overall, meat rations were the least popular economic instrument to battle climate change, accepted by a third of consumers but with pushback from 42%. And generally, younger, more educated, and urban consumers, and those displaying higher levels of climate concerns, were more likely to be supportive of meat rationing.

Why rations could work as a climate policy tool

For countries to achieve their goals under the Paris Agreement, addressing fossil fuels and the food system is critical. The former sector is by far the largest contributor to greenhouse gas emissions, and many world leaders have called for a phaseout of coal, oil and gas in favour of renewable energy as an imperative measure to meet climate targets.

Agriculture, meanwhile, is the second-biggest source of emissions, amounting to about a third of the total. Meat and dairy production alone accounts for up to 20% of global emissions, while taking up 80% of farmland and 30% of the planet’s entire freshwater supply, despite only providing 17% of the world’s calories and 38% of its protein.

The authors argue that policies that effectively reduce consumption of high-impact products are needed to fight the climate crisis, but public acceptance depends on whether economic policy instruments are deemed fair or not.

“One advantage of rationing is that it can be perceived as fair, if made independent of income. Policies perceived as fair often enjoy higher levels of acceptance,” said Lindgren.

He points out how several forms of rationing exist in modern society to lower environmental impact. These include road space rations – which have been introduced in some Chinese cities like Beijing after the 2008 Olympics, and in several trials in New Delhi in India – fishing quotas to limit the amount of catch in protected marine areas, as well as measures to temporarily turn off water supply amid drought in places like Bogotá.

Water rationing is taking place in many parts of the world, and many people seem willing to limit their consumption for climate mitigation purposes, as long as others do the same,” said Lindgren. “These are encouraging findings.”

The research follows a 2023 study that suggested rations as a way to help nations reduce greenhouse gas emissions, with carbon taxes usually favouring the wealthy, who could “buy the right to pollute” if they wanted.