McKinsey’s $250B Question: How Can Fermentation Attract Investors to Meet the Protein Demand?

5 Mins Read

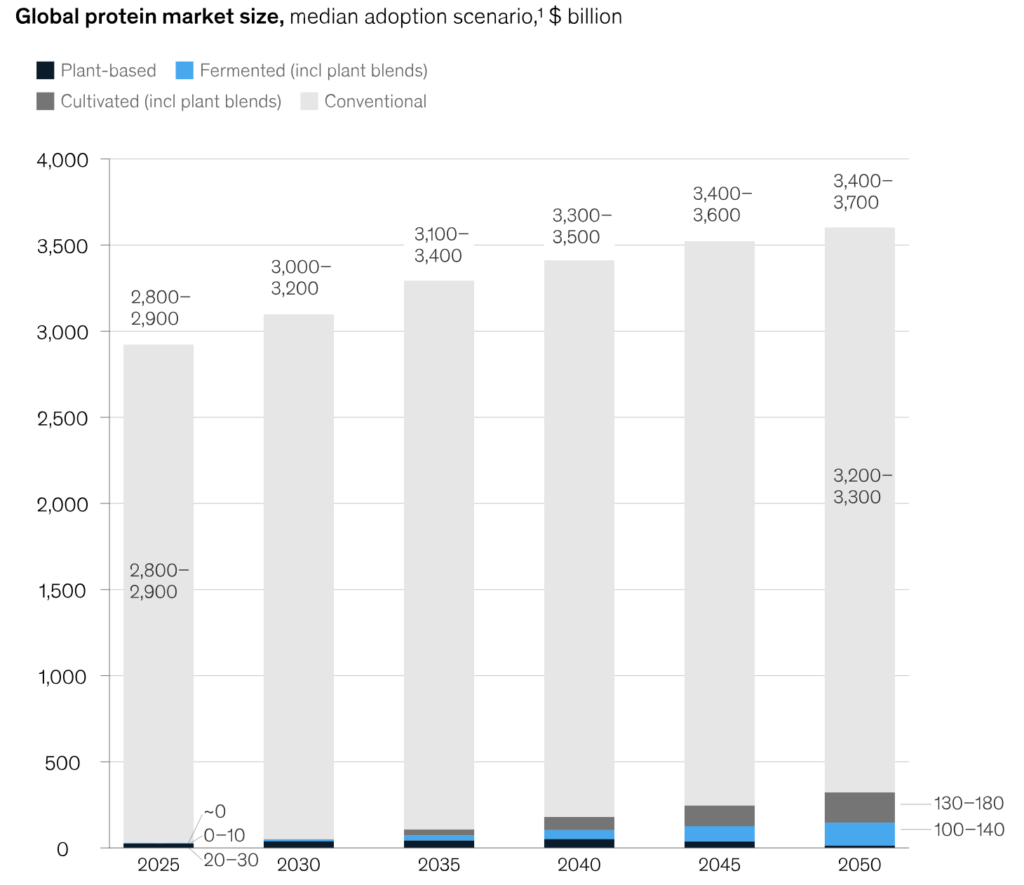

Fermentation tech could account for 4% of global protein production by 2050, but it needs $250B of investment to meet the capacity needs, according to McKinsey.

By 2050, the global population will be approaching 10 billion, a number that has spurred calls for a food systems transformation. Poverty and malnutrition rates are already on the rise, and if current agricultural patterns continue, these problems will already be exacerbated.

This is because animal agriculture is one of the leading causes of climate change, with meat and dairy production generating twice as many emissions as plant-based foods. Alternative proteins – those derived from plants, fermentation, and cell cultivation – can help solve food security challenges while keeping planetary health in check.

Fermentation-derived proteins alone could make up 4% of the global protein market by mid-century, with a valuation of $100-150B. Players in this space – whether they’re using biomass, precision or another form of fermentation – have raised $4.8B from investors in the last decade.

However, to get to this projection, they’ll need to significantly lower production costs through economies of scale. And to expand operations to the required capacity, companies would need to invest over $250 billion by 2050, according to new analysis by McKinsey.

“Over the coming five years, we expect a combination of cost parity and consumer demand to mature and derisk the novel ingredients industry, leading to a global infrastructure expansion,” the consultancy says.

“In the meantime, leaders can continue building creative mechanisms to balance capital, risk, and returns. If players can enter this investment opportunity now, they have a chance to build the food supply chain of the future.”

Process efficiencies can bring more savings than scale-up efforts

McKinsey notes that the existing capacity for fermentation-derived proteins to scale up is limited. Contract manufacturing organisations (CMOs) often have high margin expectations that aren’t in line with food industry standards – the consultancy points out that while several new capacity additions have been announced, some have “fallen by the wayside” due to macroeconomic factors.

The underlying tech and processes need to be enhanced too, while the opportunities and risks of novel ingredients are still being investigated by all industry stakeholders.

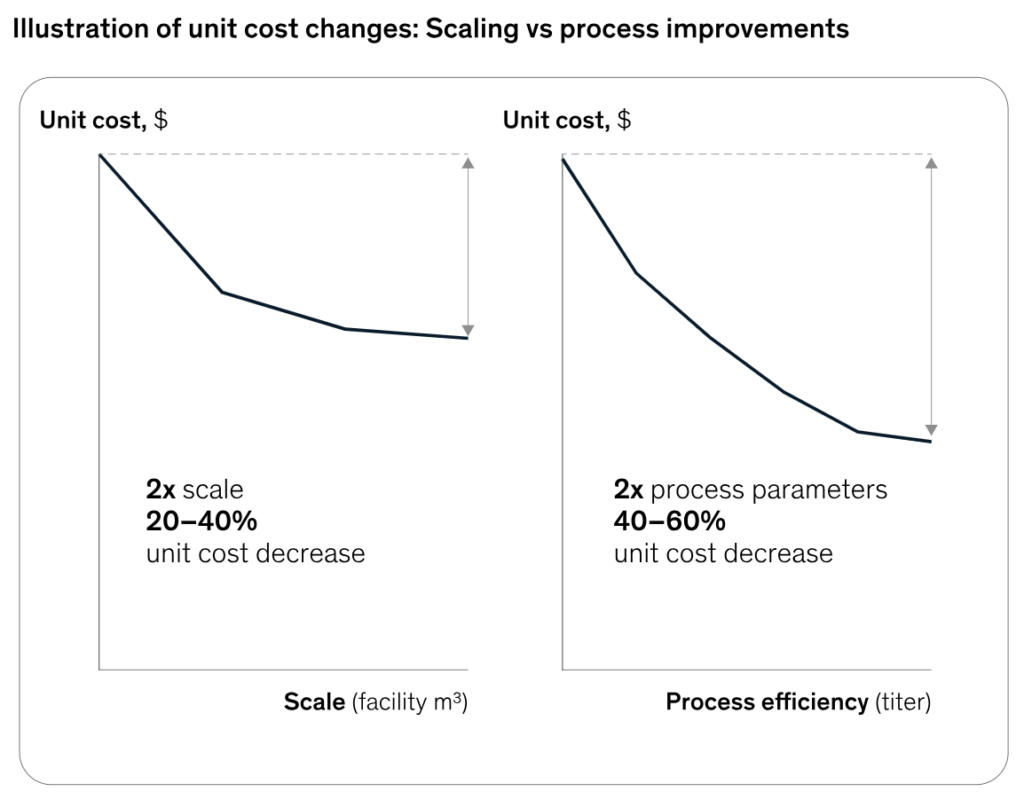

Improvements in production could bring a huge benefit, since reducing the unit costs of novel ingredients is the “single most important factor” for expanding the novel food market. By elevating bioprocesses and downstream processes, companies in the space could slash costs in half, according to McKinsey.

While scaling up is important and can bring costs down by 20-40%, process efficiencies alone can lower prices by 40-60%. These savings come from bioprocessing changes like a shift from batch-fed processes to continuous fermentation (as Australia’s Cauldron has done), or converting aerobic processes to anaerobic ones.

It’s also critical to upgrade and redesign bioreactors. Until now, most companies have used vessels optimised for the pharma industry; now, new assets that meet food-grade specifications and the margin expectation of the food sector are necessary.

Equipment manufacturers would need to strip down existing bioreactors and their surrounding components and build them from the ground up to fit the needs of the alternative protein industry. But they have yet to fill this gap, leading some startups to redesign bioreactors and build custom models out of necessity. Others, meanwhile, are exploring more modular fermentation tanks to dramatically lower capital costs and drive learning curves.

Commercial offtakes and tech risks key to unlocking investment

Apart from process optimisation, McKinsey highlights the importance of better food formulation capabilities to introduce new ingredients for consumers. Companies will be able to create products that match people’s taste, texture and health preferences – they could experiment with novel fats to improve mouthfeel or savouriness, or target a specific protein (like beta-lactoglobulin or ovalbumin) to offer specialised outputs.

A 2024 survey by the consulting giant found that 49-67% of Americans were willing to try fermentation-derived proteins, with health being the biggest driver for Gen Zers and taste for older demographics. (And surprisingly, more than half of consumers are happy to pay more for products whose animal-derived counterparts cost less than $2.)

Fermentation had a good year investment-wise in 2024, securing 43% more funding from VCs, against a 27% decline in the overall alternative protein category. To attract the required $250B, McKinsey says private capital will no longer be enough, leaving a gap the ecosystem must adapt to fill.

It explains how commercial offtakes have been the “linchpin” in securing debt in major capital expansions in other industries – think electric vehicle batteries or sustainable aviation fuel. Binding offtakes have been less common in the consumer sector, but companies are beginning to enter joint development agreements.

Moreover, technological developments around process, assets, and scale – such as redesigning bioreactors or creating new foods – can deter investors, though they’re expected to deliver material cost reductions in the next five years, which would provide a “compelling case” to financers.

These new business models are the “key underlying factor” to allow the novel foods industry to thrive. Industry players need to make choices about what capabilities to invest in, from titer improvements to ongoing IP creation, and investors must establish infrastructure-grade financing from securitised assets (and with committed offtake at market-clearing prices) to scale the industry.