7 Mins Read

Land grabs and carbon offsetting schemes have sent land prices soaring, putting a strain on farmers, rural communities and food production, and threatening food security globally.

Since the financial crash of 2007-08, global land prices have doubled, thanks in large part to land-grabbing and carbon-offsetting schemes, which has led to a “tipping point” that endangers farmers’ livelihoods and food security, according to a new report by the International Panel of Experts on Sustainable Food Systems (IPES-Food).

Powerful governments, investors and agribusinesses have appropriated large swathes of farmland in the post-recession period through new forms of land grabs, including carbon offsetting schemes, opaque financial instruments, rapid resource extraction, and industrial food production. It has led to farmers, Indigenous communities, peasants and pastoralists losing their land, culture, livelihoods and rural traditions, says the report, while young farmers now face huge barriers to accessing farmland.

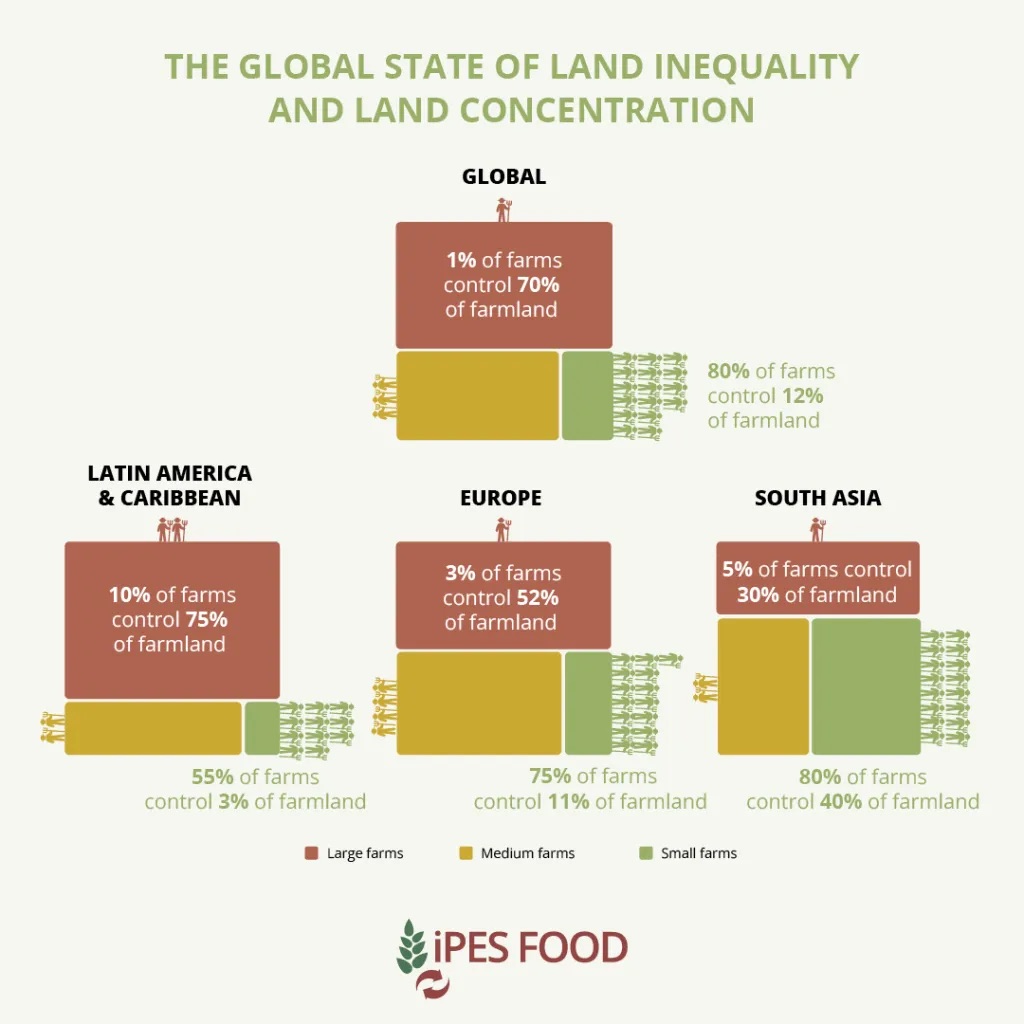

Take the area of Germany, and double it. That’s about the size of land that has been snatched up in transnational deals since 2000. Today, 1% of the largest farms control 70% of the world’s farmland.

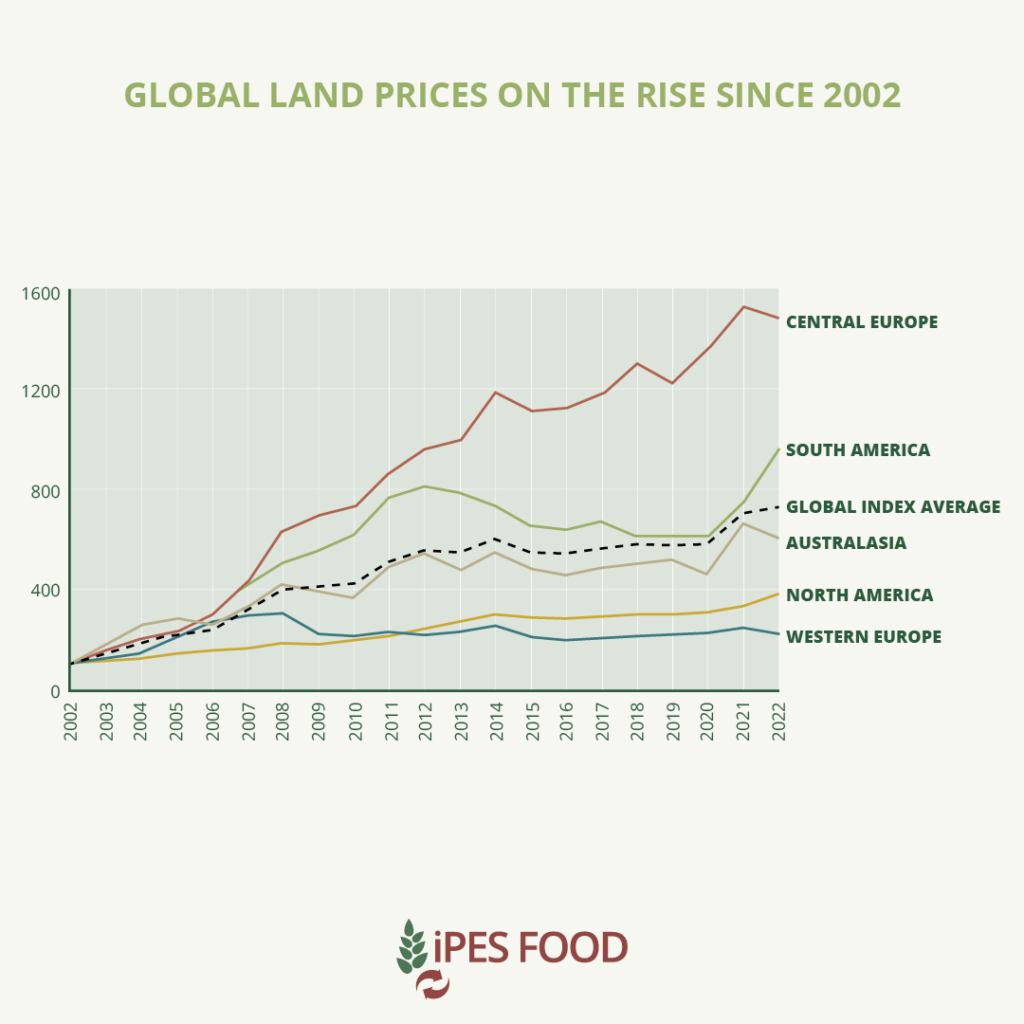

Meanwhile, land prices have hiked everywhere – in central-eastern Europe, they have tripled since 2008; in the UK, they doubled from 2010-15; in Canada, they’ve been on the rise for 30 consecutive years, spiking another 8% in 2023; and in the US state of Iowa, land is four times as expensive as it was in 2002.

The ‘land squeeze’ created by these practices is worsening land inequality, rural poverty, and food insecurity. “Imagine trying to start a farm when 70% of farmland is already controlled by just 1% of the largest farms – and when land prices have risen for 20 years in a row, like in North America. That’s the stark reality young farmers face today,” said IPES-Food expert Nettie Wiebe.

“Farmland is increasingly owned not by farmers but by speculators, pension funds, and big agribusinesses looking to cash in. Land prices have skyrocketed so high, it’s becoming impossible to make a living from farming. This is reaching a tipping point – small- and medium-scale farming are simply being squeezed out.”

How land grabs have evolved since the 2008 recession

Land Grabbing 2.0

Governments are facing renewed calls to deregulate land markets and adopt pro-investor policies, as land increasingly becomes a financial asset at the expense of smallholder and medium-scale farmers. Agri-investment funds rose tenfold between 2005 and 2018, and now regularly include farmland as a separate asset class, with American investors doubling their stakes since the pandemic.

Speaking of which, Covid-19 and the Ukraine war have revived ‘feed the world’ narratives, sparking a renewed push to secure land for the prediction of export commodities, with agribusinesses, investors and governments finding new ways to appropriate farmland.

Meanwhile, water and resource grabs – land deals that focus on securing critical resources and extracting value from them (via water-intensive cash crops, for example) – are expanding too. But there’s also been an increase in the number of land grabs that are abandoned during the process and sold to new investors, creating lasting damage to local communities and land tenure systems.

Green Grabbing

Carbon offsetting schemes – already notorious for, you know, not working – have unleashed a new wave of ‘green grabs’. Land is an important carbon sink, but with governments racing to try and meet the goals of the Paris Agreement, they’re using environmental targets to justify top-down conversation, carbon removal and offsetting schemes that exclude land users and food producers.

In fact, these green grabs now account for 20% of large-scale land deals, while over half of government carbon removal pledges risk interfering with smallholders and Indigenous populations. Countries have actually pledged to allocate land areas equivalent to the entirety of croplands globally (nearly 1.2 billion hectares) for carbon removal projects alone.

Carbon offsetting – a market that’s set to quadruple by the end of the decade – is facilitating massive land transactions and involving major polluters, including oil giant Shell and UAE-based firm Blue Carbon. Land is also being grabbed for biofuel and green energy production, including ‘green hydrogen’ projects that are water-intensive and threaten local food production.

Expansion and Encroachment

Mining, urbanisation and mega-developments are claiming prime agricultural land in many parts of the world for “rapid and often unsustainable economic expansion”. For example, mining projects alone were responsible for 14% of large land deals in the last decade, leading to displacement, conflicts and environmental degradation.

These land conversations are hurting farmers and local communities. But instead of safeguarding these people’s interests, IPES-Food says “dubious” investment laws are currently protecting the polluters. In Colombia, for instance, several transnational companies have successfully sued the government for trying to halt a large-scale mining project.

Food System Reconfiguration

Agrifood consolidation, the continuing rise of industrial agriculture, and accompanying dietary shifts are further degrading land and farmers’ control over it. The integration of smallholders into corporate supply chains is allowing companies to impose their own conditions and choices on contract farmers’ land, often leading to unsustainable land use.

Soaring land and input costs, and boom-bust cycles can make farmers’ livelihoods financially precarious, effectively forcing them to “go big or get out”. Meanwhile, the rise of “techno-centric, capital-intensive, and chemical input-intensive modes of agriculture” is driving farmland consolidation, and squeezing out smallholders.

Dietary shifts towards more animal-sourced and ultra-processed foods are putting a major strain on land, with factory farming and forest clearance closely associated with animal agriculture – livestock and feed production have made up 65% of global agricultural land use change in the last 50 years.

Additionally, the report suggests that leading food companies have pursued “deliberate research and marketing strategies” to reshape dietary habits, helping drive high meat consumption – which is linked to population growth and urbanisation – in affluent countries, and promote the “meatification” of diets in low- and middle-income nations.

Experts call for improved governance and land reforms

IPES-Food warns that if we don’t address the current trends, the land crisis could deepen inequality, facilitate rural exodus, and permanently squeeze more sustainable forms of small- and medium-scale farming out of business. This could push the agriculture sector towards unsustainable and polluting industrial models irrevocably.

The report highlights three sets of key recommendations to resolve the crisis. First, it’s vital to build integrated land, environmental and food systems governance to stop green grabs, refocus the spotlight on local communities and human rights, and ensure a just transition. Community-managed land systems are cited as the best way to reconcile food production and ecosystem protection, and these should become central to global biodiversity goals.

Second, there needs to be a shift of speculative capital and financial actors from “commodity to community”. Governments need to make the ‘true cost’ of net-zero pledges transparent, and phase out market mechanisms for carbon removals. Capping land acquisitions, giving farmers and local communities first refusal on land sales, and cracking down on bogus land-based offsets are also crucial.

Finally, the report advocates for a new generation of land and agrarian reforms, and bold steps to redistribute land back to its true owners. Better deals for farmers and rural communities are key to addressing poverty, securing livelihoods, and achieving land equality. Fair prices, adequate social security and pensions, and incentives to adopt agroecological practices will go a long way.

“Land isn’t just dirt beneath our feet, it’s the bedrock of our food systems keeping us all fed. Yet we’re seeing soaring land prices and grabs driving an unprecedented ‘land squeeze’, accelerating inequality and threatening food production,” said Susan Chomba, an expert at IPES-Food. “The rush for dubious carbon projects, tree planting schemes, clean fuels, and speculative buying is displacing small-scale farmers and Indigenous peoples.”

Sofía Monsalve Suárez, another IPES-Food expert, added: “It’s time decision-makers stop shirking their responsibility and start to tackle rural decline. The financialisation and liberalisation of land markets are ruining livelihoods and threatening the right to food.

“Instead of opening the floodgates to speculative capital, governments need to take concrete steps to halt bogus ‘green grabs’ and invest in rural development, sustainable farming and community-led conservation. Bottom line, we’ve got to make some serious changes to democratise land ownership if we want to ensure a sustainable future for nature, food production and rural communities.”