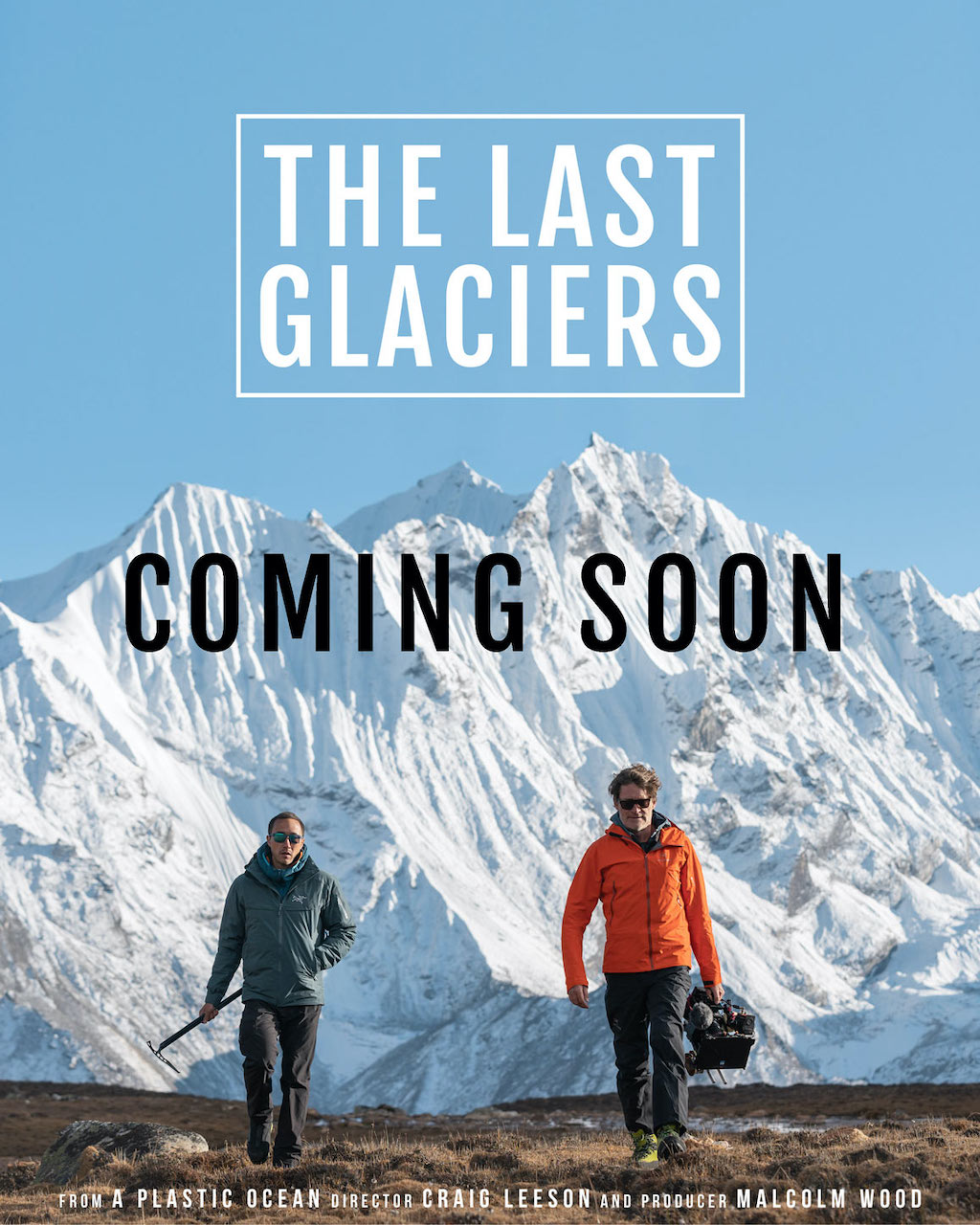

Craig Leeson Of ‘A Plastic Ocean’ On His New Film ‘The Last Glaciers’: “We Don’t Have Long To Turn This Around”

14 Mins Read

Craig Leeson is an award-winning journalist, filmmaker and television presenter best known for the acclaimed 2016 documentary A Plastic Ocean. We recently had the opportunity to speak with Leeson, who shared his journey from writing to radio, broadcasting and filmmaking and shedding light on some of the world’s most pressing issues through an adventure lens. In this interview, Leeson talks about some of his personal career highlights, his latest documentary The Last Glaciers and what needs to be done if we are to protect the planet, and ultimately, save humankind.

GQ: For our readers who might not be familiar with your work, could you share a bit about your career in journalism, film and environmental advocacy?

CL: I began my career as a newspaper journalist, which came as a result of being a fourth-generation journalist in my family. I guess it was in my blood and it was difficult for me to escape. I didn’t have intentions to be a journalist but I was a pretty good writer and it became a natural fit. I liked the voice that being a journalist gave me on various issues. I never started out to be environmentally-focused in my writing, but as someone who grew up on a beach and was close to a biosphere that was important to me – the ocean – and finding out that the ocean I used on a daily basis was polluted, journalism gave me a voice to look at the issue and address the problem in my hometown in Burnie, a coastal city in Tasmania, Australia. It was a powerful tool and a motivator to continue on with this line of work.

I started moving into long-form writing in television and documentaries, which satisfied my craving to tell a story properly.

Craig Leeson

I tend to keep moving all the time, whether it is with my work or hobbies or the skills I have. Newspaper journalism was something that once I mastered, I felt I wanted to move into another area. So I did broadcasting with radio and then television, later on becoming a news anchor and reporter in Australia. As I moved overseas to work as a foreign correspondent, moving to Hong Kong in 1996 to cover the handover and many other stories happening in Asia at the time, I found the minute-and-a-half time slot that I got to tell a news story wasn’t enough.

I started moving into long-form writing in television and documentaries, which satisfied my craving to tell a story properly. Pretty soon, in 2005, my first big documentary was for National Geographic – Marco Polo: Mystery of the Middle Kingdom – a three-part series shot on film. We were the first crew given permission to film throughout China since the 1950s and it was voted the 13th best documentary of all-time on the channel. After that, I did smaller documentary series for broadcasters, including one called the Action Asia Challenge. For someone that had grown up with a love of sports, this was when I grew a real interest in extreme sports and exploring that as a challenge. For five years, we followed different events in various countries with a specialist crew made up of people who had skills in rope work, rigging cameras on helicopters and climbing mountains to film in these extreme situations.

GQ: How did you end up making adventure-documentaries, as you have previously described your film “A Plastic Ocean”?

CL: I’ve always been interested in the environment and the relationship between the environment and our own lives, and also the lives of every single animal, insect, species on Earth. When I was a kid, I spent a lot of time on the beach and I was fascinated by the way these tiny marine creatures could live in these small pools when the tide went out and how they could survive and interact with each other. It was a personal insight into biospheres and how these creatures relied on each other to survive. Each rock pool resembled a tiny planet. To survive, they needed everything within that rock pool. It taught me that planet earth is similar – everything on our planet is carefully balanced. We interact with every species, flora and fauna, and they all have a job to do and we require them for our own life-support systems. When I was 8 years of age, I owned every single National Geographic magazine that had come out since I was 6. I still have all the issues. I’ve watched every David Attenborough documentary on air and I had every encyclopedia on birds and animals. I was fascinated by animals from a young age and that carried through.

GQ: Talk to us a little bit about your latest documentary “The Last Glaciers”. What is it about? Is it another adventure-documentary?

CL: Not only an adventure-documentary, A Plastic Ocean was an issues-based documentary. The idea was to create awareness about single-use plastics, which at the time hadn’t been covered in-depth and with scientists. The Last Glaciers is similar to that in that it is also issues-based on climate change, but it is even more an adventure. I use adventure as a tool to get people involved in a story – people who wouldn’t normally have an interest in climate change or who wouldn’t understand the topic. People who like me, until I started wondering what was happening to the climate, found it difficult to understand the science behind it, which is often dense and hard to get a grasp of. I realised that disconnect. The story wasn’t being told in a way that everyone could understand. That’s why we told the story using extreme sports and other narrative tools within the documentary to get people interested in it.

I use adventure as a tool to get people involved in a story – people who wouldn’t normally have an interest in climate change or who wouldn’t understand the topic.

Craig Leeson

GQ: How did the “The Last Glaciers” adventure begin?

CL: The idea for The Last Glaciers came during a trip to Europe. My good buddy Malcolm Wood offered to help train me in mountain skills so we could attempt a climb on Mount Everest. But the French alps was having its worst winter ever – it was warm, there was no snow and we were hearing how glaciers across Europe were melting. We looked in to the causes and were both alarmed by what we found. It was a story we thought had not be told comprehensively, and it needed to be, and Malcolm partnered with me as my Producer for this project and has shown me a whole new way of experiencing the mountains through the extreme sports that he practices.

GQ: Adventure films can have the effect of attracting more people to visit places like Mount Everest, now suffering from a decade of climber abuse or to go on mega cruises to Antarctica so they can post on social media about being “one with nature”. Many activists have spoken out against this brand of extreme nature tourism. What do you think about this?

CL: Everything we do needs to be in moderation and in consideration of our footprint. I don’t have a problem with extreme adventure tourism as long as it is managed very well by operators, by the governments who license it and by the people who go. We all need to be responsible for our footprint and aware that every single thing we do – whether it is the breath we take or the food we eat or the places we visit – has a profound effect on the locations that we are in and the animals and species that we are sharing the place with. That is what’s critical. It’s about self-awareness and empathy. I think that one of the biggest problems we have as a species is that we don’t educate ourselves at a young enough age about the interactions we have on a daily basis with other species, including plant and animal and insect life. Ultimately, the impact we have on the planet determines how our future is going to look and how we survive. Extreme tourism is no different or any other tourism. If you put too many people into fragile or even non-fragile locations, that will have an impact. If that isn’t managed properly, then that impact is detrimental. So it comes down to common sense, protecting resources for future generations and understanding that money isn’t our most valuable resource. The environment is our valuable resource and from it we derive financial benefit, including tourism, and if we are to continue doing so, we need to protect the environment.

GQ: It’s been four years since “A Plastic Ocean” and the film is undoubtedly one of the reasons the whole world started talking about plastic waste. How do you feel about it today? Did you know it would be such a catalyst when you made it?

CL: I knew what we were filming, especially as we were filming it, was becoming more and more important. When we started, we didn’t know what we would find. We knew there was a problem in the North Pacific Gyre, and our producer Jo Ruxton, whose idea for the film it was, went to do research there and said there was a major problem. We thought that if it was in one part of the ocean, it must be in other places too. But no one could tell us that was the case, so we started out with this little information and went around 21 different locations with a fair idea that what we would end up finding would be bad. When we did, we found out that the problem was far worse, more than we could ever imagine. Instead of getting the answers we hoped to find, we were getting more questions. That’s why the documentary became one that was based on the ocean into one that also focused on land and human health. We discovered so much as we went along with the film. It was a surprise to myself in terms of the content we had. But I knew what we had was extremely powerful and had to be told. Even today, I am almost speechless about the effect it has had.

GQ: How have you changed as a person from making that film? Did you end up altering any of your daily habits?

CL: The response we have had, with some people telling me that the film changed their lives and how they live with single-use plastics, it makes me proud of what we have achieved. It drives me to do more and to create more awareness about these problems, which is what led me to start the project on The Last Glaciers. I realised that these are things we aren’t taught in school, even though it should be. We are deliberately led away from these greater issues that impact all of us because of the economic society we live and this notion of perpetual growth, which is brain-damaged thinking, but it’s the way society is currently structured.

I want the lightbulbs to go off at the same time as they do with me. I want to lead people into these issues with an understanding so that they’re armed with knowledge as an individual to make changes.

Craig Leeson

I think this needs to be addressed, and that’s why with my skill-set that I am fortunate enough to have with documentaries and filmmaking, I feel I need to use it to bring awareness to other people as that very awareness comes to me. I use myself as a basis for how I write and present my films. The style I use, I take the audience with me to allow people to see what I’m seeing. I want the lightbulbs to go off at the same time as they do with me. I want to lead people into these issues with an understanding so that they’re armed with knowledge as an individual to make changes.

GQ: You’ve been face-to-face with the most pressing ecological disasters of our time, seeing first hand how much plastic waste we have dumped into the oceans, for example. Do you feel angry when you think about what humanity has done to the planet?

CL: I do. There is a scene towards the end of The Last Glaciers where we film the receding glaciers from the Himalayas, where I expressed extreme disappointment and anger at how stupid humans can actually be in terms of the damage were doing. It doesn’t affect the planet as much as it does us. It’s not the planet that needs saving, it’s us. We had a NASA scientist who travelled with us across Antarctica, who said to me in the film that the Earth will survive, but whether humans will be around to enjoy it is another matter. That’s a very profound point. We’re just a blip in the development of the planet and other species on it. What we are doing to our planet is what we are doing to ourselves. If we don’t maintain the life-support systems that we need as a species, then we won’t survive. There are many scientists who think we don’t have the capability to protect the environment enough to survive, that the decline of humanity is such a rate that our species will not endure. In my lifetime, 60% of all species on Earth have been wiped out. That is an incredible amount of biodiversity gone – and that is biodiversity we rely on for our own survival. So it’s not that difficult to imagine us as the species wiped out by our own mismanagement.

What we are doing to our planet is what we are doing to ourselves. If we don’t maintain the life-support systems that we need as a species, then we won’t survive.

Craig Leeson

GQ: Do you feel hopeful that we can change? What do you believe is required for big changes to happen in order to solve the climate emergency?

CL: Yes. We can be incredibly stupid but also incredibly smart. We have come a long way. Take the Industrial Revolution and the many pains we have now in relation to it. We have designed our way into that problem and therefore, we have the capacity to design our way out of it. The design of single-use plastics, for instance, was a flawed design and we know that now. Since our film A Plastic Ocean came out, 147 countries have recognised and started to ban or introduce legislation to deal with the problem. We can do the same thing to fossil fuels. Today, we are seeing this. There is more than US$2.5 trillion invested into renewable energy. We are seeing entire communities run on clean energy and its providing a new green economy that is lowering pollution and with it bringing value for us to our human health while providing young entrepreneurs the opportunity to profit from being kind to the environment and humanity.

I’m seeing this on a daily basis, but we need it to speed up to survive. So I am hopeful and I become more optimistic when I talk to young people around the world. It’s the older generation that worries me – my parents and my generation. We need to change our habits and provide the younger generation with the tools to get on with saving us and saving themselves and their kids. We don’t have long to turn this around. The climate crisis is here, the feedback loops are getting bigger, extreme weather events are more frequent and the habitable space we have on Earth is getting smaller.

GQ: Do you think that climate awareness has increased at all during the coronavirus pandemic? Are people waking up to the ecological crisis humanity has caused, more so than before?

CL: Yes it has. People are seeing that they can survive with fewer resources. We realised we don’t need to travel as much as we do, we don’t need to consume as much as we do, we don’t need to buy the latest pair of sneakers or fast fashion item. It’s perfectly acceptable to wear jeans that are 10 years old. We have seen pollution levels drop and that isn’t just good for the environment. Considering that 8 million people die every year as a direct result of pollution, we know we can be saving a lot of lives and quickly. We know that we have it within ourselves and system structure to make changes. What we need to be careful about now is that the government and corporations do not capitalise this for their own benefit. We’re starting to see this happen with a lot of products and legislation, particularly those that limit what we can do as humans in terms of freedom of speech and how we interact with one another. We need to take the positive from the coronavirus and apply that to the future. I hope to see this happen. Ultimately, we need to change our economic and financial paradigms in which we live.

We don’t have long to turn this around. The climate crisis is here, the feedback loops are getting bigger, extreme weather events are more frequent and the habitable space we have on Earth is getting smaller.

Craig Leeson

GQ: Do you believe film is an important medium as a communicator and visualiser of the destruction we have caused on Earth as compared to other forms, such as written word?

CL: I think they all play a role. I read a lot. I read more literature than I do watching films. But many people are visual and need to see it to understand it. So film is incredibly powerful if used correctly as an appropriate tool, in an objective way as possible. I certainly found with these issues-based films that it is extremely effective. I knew with A Plastic Ocean we would strike a chord but I didn’t realise that tens of millions would see it, that it would affect people and change the way governments handle the situation. So for me, film is incredibly important but everything needs to come together to work. Having a great crew, having talented cinematographers, like-minded producers and distributors who make sure that voice is heard. It is important in the end of the film to also offer solutions and that’s what we want to do – to show the problem but lead the audience with the understanding that they can do something.

GQ: What do you hope viewers of “The Last Glaciers” will take away? What’s the key message you want to impart?

CL: Glaciers are disappearing because of the way we have burned fossil fuels and put greenhouse gases into the atmosphere. We need to change our system and move into renewable energy. We show how individuals can change their lifestyle to be part of the big solution to stop global warming. We need to fundamentally change the way we live.

GQ: Can you share with us some of your most memorable career highlights?

CL: My personal career highlight would be working with Sir David Attenborough. That was something I had always wanted to do and did with A Plastic Ocean. For him – the greatest documentary filmmaker – to say that the film was the most important of our time, that for me is a professional highlight.

GQ: Final question – team rice or team noodles?

CL: Noodles.

The Last Glaciers is planned for release in 2020/2021 and is now seeking your help to raise funds via their Indiegogo campaign, where supporters can purchase “perks” to support the film while contributing to forest restoration projects.

All images courtesy of Craig Leeson.