Instant Golden Milk: Researchers Tap Into Turmeric for More Nutritious Plant-Based Milk

4 Mins Read

Scientists have developed a way to increase the presence of curcumin – the bioactive compound found in turmeric – in plant-based milk, as part of an instant ‘golden milk’ powder.

Golden milk. Turmeric latte. Call it what you want – it’s been impossible to escape this beverage in coffee shops around the world in recent years.

While Indians have been drinking turmeric milk – literally ‘haldi doodh’ – for generations, ‘golden milk’ took a life of its own and became an internet phenomenon sometime in late 2015. Far from the simple turmeric and milk concoction found in India, this spawned countless variants: some used coconut milk, some had a host of other spices, others were iced, and yet others (read: Starbucks) added espresso for some reason.

But now, researchers at the American Chemical Society have come up with a new way of making the internet-famous drink that presents even further health benefits.

Turmeric’s widespread benefits – from being anti-inflammatory and anti-oxidating to fighting cancer, heart disease and depression – are largely thanks to the polyphenol curcumin, which is a bioactive compound. The researchers wanted to find out if there was a way to extract and store curcumin within plant-based milk.

“If we can incorporate bioactive compounds like curcumin into plant-based milks to bring them up to the same nutritional level as cow’s milk, why not?” said Anthony Suryamiharja, a graduate student at the University of Georgia who is part of the team.

Creating a supercharged plant-based golden milk

Clearly, curcumin is great for us. But the problem is that it’s hard to separate the polyphenol from turmeric – it’s an energy-intensive, time-consuming process that requires complicated extraction techniques involving organic solvents. Furthering the challenge, curcumin breaks down over time, which shortens its shelf life.

The other issue is that curcumin is fat-soluble. In water, it’s hard to dissolve and degrades rapidly. Its molecules sick together as crystals, which makes it more difficult for the gut to absorb the compound and reap its benefits.

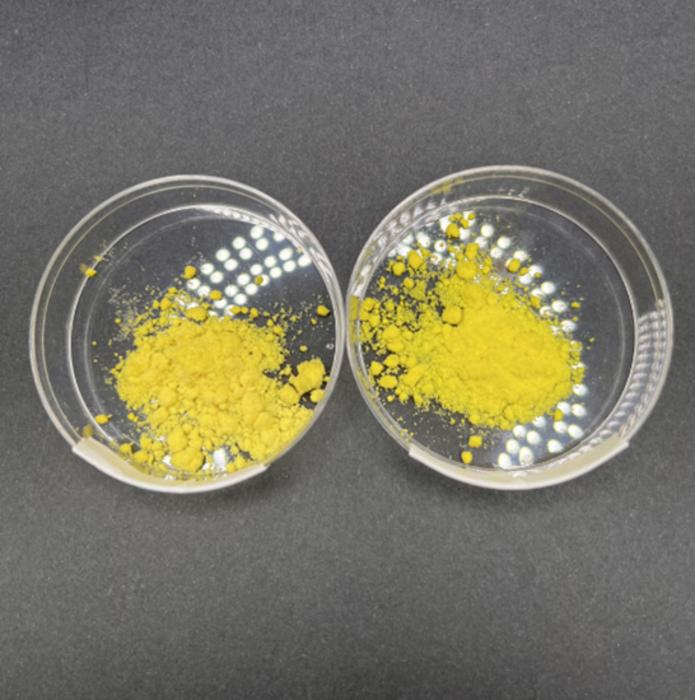

To overcome these two hurdles, the researchers added turmeric powder to an alkaline solution – the high pH removes hydrogen atoms and makes the curcumin molecules negatively charged, allowing them to separate and dissolve more easily than in plain water. Doing so gives the solution a deep red hue, but when added to soy milk, it turns into a dark yellow shade.

Then, the scientists added a buffer to neutralise the pH level to around 7. This has two functions. One, like highly acidic foods, those with high-PH bases are unpleasant in flavour. Two, this encapsulates the curcumin molecules in the oil droplets suspended within the soy milk.

So when we consume this milk, our bodies recognise the curcumin as fat and digest it as so, making the curcumin more bioavailable – in other words, it’s more likely to be absorbed by the body and present the health impacts it’s known for.

Golden milk research could open up food waste opportunities

The American Chemical Society says that once the soy milk was neutralised, it was ready to consume. But in an effort to preserve it further, its team removed water from the solution through freeze-drying, resulting in an instant golden milk powder.

Moreover, by encapsulating the curcumin in the fat droplets, the compound is protected from air and water, which keeps it shelf-stable for longer.

The researchers chose soy milk for its high amino acid content, but they suggest that this process could be applied to other plant-based milks too. It’s a win for this segment – 44% of American households purchased milk alternatives last year, and nearly half did so because they think these are better for their health or have more nutrients than cow’s milk.

More research is needed before this instant golden milk appears on grocery shelves, but Suryamiharja believes it tastes good despite him not drinking a lot of turmeric lattes. His team hopes to explain the chemistry behind seemingly simple foods through their work, as well as improve the nutritional value and convenience factor.

“People usually do a lot of simple things in the kitchen, but they don’t really realise there’s a chemistry behind it. So, we’re trying to explain those unspoken things in a simple way,” explains Suryamiharja.

But the experiment also represented further opportunities. The pH-driven extraction method can be used on different plant compounds with similar efficiency – think blueberries, which are rich in anthocyanins, a water-soluble polyphenol.

“When we use the same method, within around a minute we can extract the polyphenols,” explains Hualu Zhou, who was part of the research team. “We want to try and use it to upcycle by-products and reduce the food waste from fruit and vegetable farming here in Georgia.”