‘Immense Potential’: Indian Government Body to Develop Cultivated Fish in Partnership with Neat Meatt

6 Mins Read

In a first-of-its-kind partnership, the Indian government is embarking on a project to create cell-cultured seafood with cultivated meat startup Neat Meatt Biotech.

The ICAR-Central Marine Fisheries Research Institute (CMFRI) has signed an MoU with New Delhi-based biotech company Neat Meatt to develop cultivated fish, in what is a landmark project for the world’s third-largest seafood consumer. The initiative aims to ensure India keeps up with international progress and tackle climate and food security issues.

The project aims to tackle India’s growing demand for seafood – fish consumption has swelled by 88% in just over a decade – reduce pressure on wild resources, keep up with global progress on alternative proteins, and provide solutions to climate change and food insecurity.

Proof of concept could be shown within two months

The partnership will initially focus on developing cell-cultured varieties of high-value fish species – like kingfish, pomfret and seer fish – which are extremely popular in India, especially among the coastal belts. Based in Kochi, CMFRI has entered into a collaborative research agreement with Neat Meatt, a cultivated meat manufacturer and solutions provider, to help develop these seafood products.

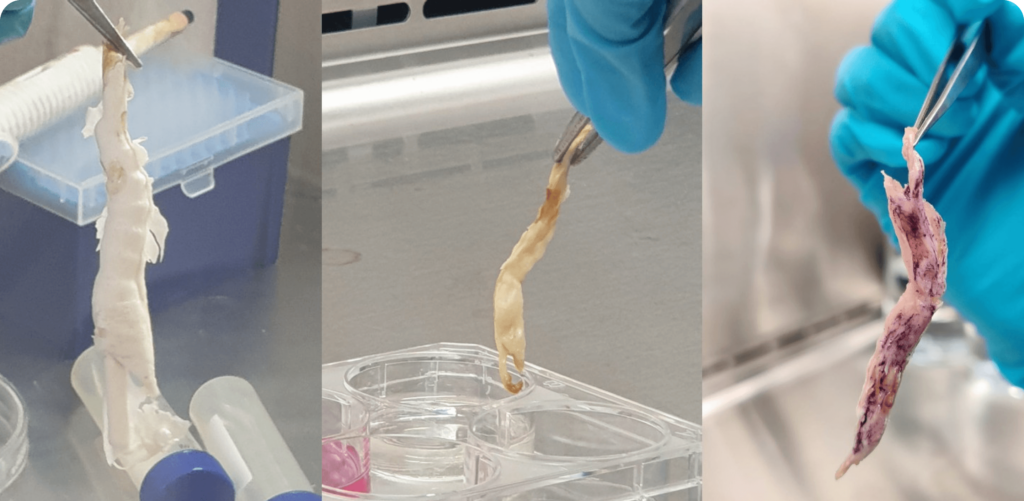

An MoU signed by the two parties reveals that CMFRI will conduct research into early cell line development of high-value marine fish species. This involves isolating and cultivating fish cells for further R&D. Additionally, the marine research organisation will handle genetic, biochemical and analytical work, equipped with a cell culture laboratory with basic facilities, providing a solid foundation for research in cellular biology.

Meanwhile, the project will leverage Neat Meatt’s expertise in cell culture tech, with the firm leading the optimisation of cell growth media, development of scaffolds or micro-carriers for cell attachment, and scaling up production through bioreactors. The company will be responsible for providing the necessary consumables, manpower and additional equipment required as well.

Neat Meatt co-founder and CEO Sandeep Sharma is confident that the partnership’s proof of concept could be established within a couple of months. But Kajal Chakraborty, principal scientist at CMFRI, told the Hindustan Times that the product may take a decade to reach the market. “Just like other meat, we will use cell line cultures to produce fish meat. It’s even more difficult to grow meat of higher vertebrates in laboratory settings,” she explained.

CMFRI director A Gopalakrishnan added: “This project aims to accelerate development in this field, ensuring India is not left behind in this emerging industry.”

Why India decided to invest in cultivated seafood

India’s seafood market is worth $57.15B, according to one estimate, and is set to expand by 7.6% annually. And last year, its seafood exports reached an all-time high, shipping out 1.7 million tonnes worth $8.09B. But with growing awareness about the seafood industry’s climate impact, there have been calls to switch to lower-carbon production methods.

While estimates suggest that carbon emissions of fish caught in India’s marine fisheries are 17.7% lower than the global average, in terms of overall climate change impact by 2050, the country remains in the medium to high category. The country has a burgeoning alt-protein sector, with 113 companies working across plant-based, cultivated and fermentation-derived meat, dairy, seafood and eggs.

But even though several alt-seafood startups exist in India (such as Seaspire, Mister Veg, VegetaGold, Veggie Champ and The Mighty Food), only two companies – Klevermeat and Myoworks – are known to be working on cultured seafood. So this collaboration between CMFRI and Neat Meatt holds promise.

“This public-private partnership [PPP] marks a crucial step in bridging the gap between India and other nations like Singapore, Israel, and the USA, who are already advancing cultured seafood research,” said Gopalakrishnan, who praised cultured fish’s “immense potential for environmental and food security”. He added: “This collaboration leverages CMFRI’s marine research expertise with Neat Meatt’s technological know-how in this field, paving the way for a sustainable and secure future for seafood production in India.”

Explaining the reason behind this partnership, the Good Food Institute (GFI) India’s science and technology specialist, Chandana Tekkatte, told Green Queen: “There is a growing recognition that by enabling more large-scale international scientific and industrial collaborations (leveraging our decades-old bioeconomy expertise), India could become a production powerhouse in the emerging cultivated meat industry and pave the way for other emerging economies.

“The DBT-BIRAC is also encouraging such PPP models to help accelerate R&D breakthroughs in cultivated meat and seafood in India, similar to the momentum seen in Singapore, Israel, and the US. The Ministry of Science and Technology has also been working closely to advance research in cultivated meat and other smart protein categories within the nation’s priorities for high-performance biomanufacturing.”

In another instance of government support for cell-based meat in India, the Ministry of Science and Technology’s Science and Engineering Research Board included cultivated meat research under its Competitive Research Grant Programmes in 2021.

The rise of cultivated proteins in India

Tekkatte said India’s cultivated meat and seafood industry is still in its infancy but stands to benefit significantly from India’s thriving pharmaceutical sector, which is set to reach $150B in 2025. “This sector has a proven track record in affordable, high-quality manufacturing, and cultivated meat companies have the opportunity to tap into its vast infrastructure and resources,” she explained.

She added that key early-stage scientific advancements in cultivated meat and seafood have been led by startups in cell line development (Neat Meatt, Klevermeat, Clear Meat), media formulations (Clear Meat), and scaffolds (Myoworks) over the last five years. These have helped build the foundation of the sector and “continue to inspire future research endeavours”.

Previous GFI India research has revealed that one in four Indians would consider giving up conventional meat, seafood, dairy or eggs in the future, citing issues like hygiene, smell, ease of cooking and heaviness on the stomach, as well as animal welfare and impact on the climate. Meanwhile, a three-country study from 2019 on consumer acceptance of cultured meat revealed that 56% of Indians are “very or extremely likely” to buy cultivated meat regularly. “Consumer education and perceptions will play an important role in advertising, marketing, and sale of cultivated meat,” said Tekkatte.

This will also be influenced by prices. “The cost of cultivated meat production will come down with scale — and the scale-up principles of cultivated meat biomanufacturing are sound and have been demonstrated in biopharmaceuticals and vaccine manufacturing industries,” explained Tekkatte.

She added that the Food Safety Standards Authority of India’s regulatory framework “needs to be made more dynamic and evolve in tandem with innovations”. Cultivated meat falls under the Food Safety and Standards Regulations (FSSAI) set out in 2017, which rules that if a product or ingredient doesn’t have a history of human consumption – or is obtained using new tech with engineering processes that significantly alter its composition – it’s classed as a non-specified or novel food product.

In 2020, the FSSAI formed the Working Group on Cultured Meat with regulatory and scientific experts to study the possible regulatory pathways for cultivated meat in India. “Early engagement with cultivated meat companies intending to apply for pre-market approvals under the Non-Specified Foods Regulations during the development process would enable the regulatory body to have oversight of the development process, leading to effective, timely guidance to the companies to ensure regulatory compliance and appropriate data submission to reduce approval timelines,” Tekkatte outlined.

“The significance of channelling resources into the cultivated meat industry is particularly relevant in India, with our unique vulnerability to climate change and public health crises. With this massive decrease in land use, additional opportunities arise for the diversification of crops towards direct food consumption,” she said. “As we funnel more investment towards R&D and infrastructure, there’s no doubt that the cultivated meat sector can grow exponentially in India and help cater to the increasing protein needs of the global population.”