Explained: What India’s BioE3 Policy Means for the Alternative Protein Industry

7 Mins Read

India’s new BioE3 policy puts alternative proteins and future food in sharp focus – what does the biomanufacturing strategy mean for this sector?

On Saturday, India announced a biotechnology policy focused on the economy and climate, with smart proteins and functional foods – as well as climate-resilient agriculture – among six pillars of the strategy.

With BioE3 (which stands for Biotechnology for Economy, Employment, and Environment) being approved by the Union Cabinet, India is aiming to foster “high-performance biomanufacturing”, with a focus on accelerating tech development and commercialisation by getting up biomanufacturing hubs and biofoundries.

The policy is designed to strengthen the country’s net-zero goal of 2070 and its Lifestyle for Environment strategy (which encourages green behaviours), and speed up ‘green growth’ by promoting a circular bioeconomy. The government aims to position India as “a potential leader in the fourth industrial revolution”, science and tech minister Dr Jitendra Singh said in a press conference yesterday.

The administration defined “high-performance biomanufacturing” as the ability to produce products from medicine to materials, promote advanced biotech processes for the manufacturing sector, as well as address farming and food challenges.

The six focus areas are high-value bio-based chemicals, biopolymers and enzymes; smart proteins and functional foods; precision biotherapeutics; climate-resilient agriculture; carbon capture; and marine and space research.

That alternative proteins have been highlighted as an economic pillar of the world’s most populous nation is a big deal for the industry. Here’s how it happened, and what comes next.

How alternative proteins became part of India’s BioE3 policy

It all started in July 2023, when the Prime Minister’s Science, Technology, and Innovation Advisory Council met to identify key areas of scientific importance for high-performance biomanufacturing, explains Sneha Singh, acting managing director of the Good Food Institute (GFI) India.

The secretary of the Department of Biotechnology, Dr Rajesh Gokhale, presented smart proteins as part of the initiative. Since then, the department has been holding closed-door meetings with an expert committee to identify a strategic roadmap and period goals for the alternative protein industry.

GFI India – a think tank focused on alternative proteins, which include plant-based, cultivated, and fermentation-derived proteins – was part of these meetings. “The inclusion of smart protein as part of the BioE3 policy is the government’s signal to the world that India is looking to be the hub for R&D and cost-efficient manufacturing in this emerging sector,” Singh tells Green Queen.

She adds that other agencies have been engaging on smart proteins too. The Food Safety and Standards Authority of India has been working on regulatory clarity, while the Ministry of Food Processing Industries (MoFPI) will showcase plant protein technology at the World Food India 2024 event.

The Biotechnology Industry Research Assistance Council has also backed entrepreneurs through early-stage ignition grants, and the Department of Science and Technology has led calls to promote translational R&D.

How will smart protein startups profit from BioE3?

The biomanufacturing policy “acts as a catalyst” for alternative protein’s growth in key foundational areas, according to Singh.

“By providing dedicated R&D and innovation support, the policy will accelerate the development of new technologies and processes that can pave the way towards the nutrition, price, and taste parity of smart protein products, making them a truly competitive alternative to their animal-derived counterparts,” she explains, echoing one of GFI India’s policy briefs for stakeholders in the government and the industry.

Meanwhile, the establishment of manufacturing hubs and biofoundries will offer “crucial support” for large-scale commercialisation. “This increased production capacity can significantly improve the accessibility and affordability of smart protein products, enabling them to reach a wider consumer base,” she says.

“Smart protein startups will gain significant momentum through dedicated R&D and innovation support, greater investments, and a nurturing ecosystem,” she adds. “The policy will foster a collaborative environment, facilitating the exchange of knowledge and resources between industry and academia, and encouraging public and private partnerships, leading to faster development and commercialisation of smart protein technologies with biohubs and biofoundries.”

Agriculture accounts for 15% of India’s emissions, and two-thirds of this comes from livestock farming. Singh believes the circular bioeconomy focus resonates with the goals of food sustainability: “By reducing reliance on animal farming, alternative proteins address environmental concerns, further strengthening the smart protein sector’s appeal.”

Who else stands to benefit?

But it’s not just companies that benefit from India’s new policy. “With the growing demand for millets, chickpeas, and other indigenous crops for smart protein end-products, farmers and crop-producing communities can explore new avenues with these resource-efficient crops to create a robust supply chain and contribute to rural economic development,” outlines Singh.

“The policy’s commitment to expanding the skilled workforce is another vital aspect, as it aligns perfectly with the sector’s rapid growth and immense economic potential,” she adds. This will “open several doors for students and the nascent workforce”, who’d be able to enter a fast-growing industry through dedicated coursework and multidisciplinary roles.

This is something Dr Gokhale touched upon in the press conference too. “[BioE3] is expected to generate substantial employment opportunities, particularly in tier-II and tier-III cities, where biomanufacturing hubs will be set up,” he said. “These hubs will leverage local biomass sources, thereby enhancing economic development in these regions.”

Looking at things longer-term, all these efforts will combine to bring benefits to consumers. They will “gain access to a wider array of better-quality, tastier, and more nutritious smart protein products, catering to their diverse preferences”, notes Singh.

At around 20%, India has the largest vegetarian population in the world. A survey by GFI India and Kantar last year found that one in four early-adopter consumers would consider giving up conventional meat, seafood, dairy or eggs in the future, with issues like hygiene, ease of cooking, animal welfare, and planetary impact top of mind.

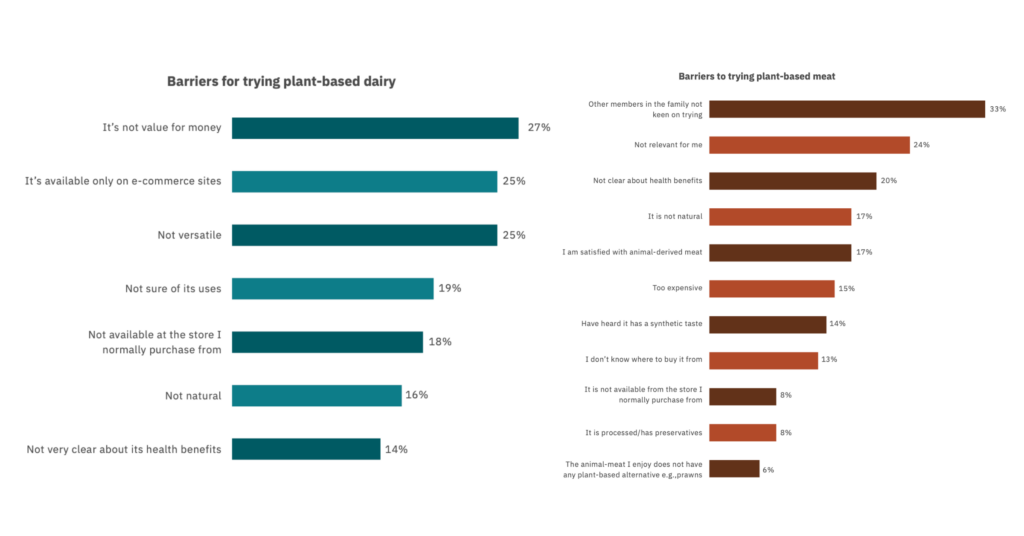

Meanwhile, a perceived ‘unnaturalness’, lack of clarity on health benefits, and taste and price are among the major consumption barriers for alternative proteins in India. People over 45 feel these products are not relevant to them and possess a synthetic taste, while product availability is a key hurdle for many Indians. The amped-up focus on biomanufacturing would help address many of these challenges.

Looking to the future

India’s bioeconomy has grown immensely in the last decade, going from $10B in 2014 to more than $130B in 2024, according to figures cited by science and tech minister Dr Singh. This trajectory is set to continue, with forecasts valuing the sector at $300B by 2030.

“Notably, the once fledgling pharmaceutical industry is now a $50B behemoth, fulfilling a significant portion of global demand for medicines and vaccines,” says Singh. “Today, a similar opportunity awaits in the smart protein sector. India’s robust biopharmaceutical and bioprocessing industries have already laid a strong foundation, establishing us as a key player in R&D, innovation, and the large-scale manufacturing capabilities needed for the smart protein sector globally.”

Singh references the government’s Make in India initiative, the propulsion of entrepreneurial ventures, skilled talent generation, and technological advancements as markers of India’s potential to become a global manufacturing hub for smart proteins.

“Leveraging its biomanufacturing capabilities, India can innovate and scale up production of crucial equipment and ingredients cost-competitively, leading the way for technological breakthroughs to produce high-quality and low-cost food manufacturing while fostering robust bioeconomy growth,” she says.

Just earlier this month, the central government introduced 109 new climate-resilient crop varieties for the country’s farmers – for Singh, this is a sign India is “fully committed to making our food systems more productive while also being more cognisant of the impacts of climate change”.

This effort also shares synergies with alternative proteins. “Many of these climate-positive crops, such as pulses, legumes, and beans, have applications for plant-based proteins,” she says. “Beyond climate resilience, government support for research on crop breeds with higher protein content and reduced off-flavours can be hugely impactful in increasing the commercial potential of these crops through plant protein value chains.”

India has also launched a joint climate-smart agritech accelerator programme with Australia. And last week, Mumbai-based Zydus Biosciences agreed to buy a 50% stake in biomanufacturer Sterling Biotech from Californian precision fermentation pioneer Perfect Day – they plan to open an animal-free protein factory to supply to global markets.

“Climate-resilient agriculture is not solely about safeguarding food systems from the effects of climate change – it is also about reducing their contribution to this global challenge,” says Singh.