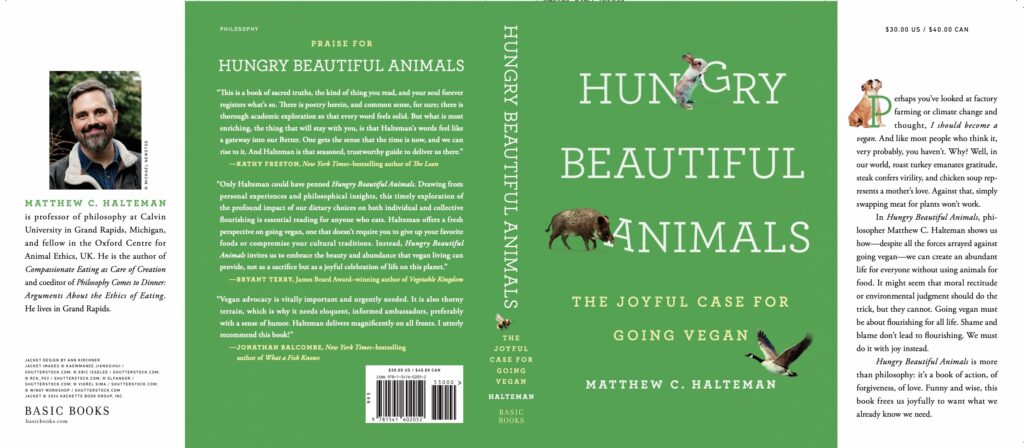

Going Vegan Can Progressively Lift Us Into Heightened Consciousness – Exclusive Book Extract from Hungry Beautiful Animals

5 Mins Read

In this excerpt taken from Chapter 5 of the new book Hungry Beautiful Animals, author and philosopher Matthew Halteman argues that choosing not to eat animals can usher us into a higher state of consciousness.

On the day that a crestfallen bulldog and a carrot-desecrated yard conspired with the universe to convince me of the moral equivalence of dogs and pigs, I would still have been deeply skeptical of the idea that orcas enjoy personal experiences in complex family cultures within a shared dolphin world.

As impressive as dolphins are, I might have argued back then, their accomplishments are still modest compared to skyscrapers and symphony orchestras. And when you’re out there trying to be taken seriously as a vegan, you’re not going to lead with animal biographies, especially those of apex predators allegedly so brutal in their ascendance that they deserve the epithet “killer.”

The only quicker way to achieve Annoying Vegan status is to mount a campaign for termite liberation at a pest control trade show. A better strategy, or so it seemed to me in the early years of going vegan, was to keep the focus tight on shame-inducing comparisons between the two classes of animals that most depend on our mercy: the companions whose bodies we hug, and the “food animals” whose bodies we eat.

As my inner ecology has become more unified and my vegan practice has gained confidence, it’s slowly dawned on me that the stories of free-living creatures striving to flourish in a wider world that provokes their desires and challenges their efforts can powerfully unveil the beauty of a new vegan normal in ways that appealing to the suffering of domesticated animals often cannot. This is certainly not to say that free-living animals are more beautiful or morally important than their domesticated fellow creatures. To render any such comparative judgment absurd, simply feast your eyes on the beauty and dignity radiating from every page of Isa Leshko’s magnificent Allowed to Grow Old: Portraits of Elderly Animals from Farm Sanctuaries. The point is to interrupt our regularly scheduled program of seeing animals primarily in contrast to assumed human ascendence as dependent, oppressed, and suffering, so that exposure to their flourishing might invite us to imagine who they are beyond the human/animal binary that renders them lesser-than before we even know the first thing about them.

By retraining our consciousness of the lives of animals on narratives of free-living creatures doing well, we can transform our default vision of them as underlings, even and especially the domesticated animals we thought we already knew. By these lights, astonishing capabilities for living well on their own terms come brilliantly into focus that must hide in plain sight when we experience animals primarily within the overwhelmingly negative valences of our most common inherited conceptions of them. Instead of seeing animals merely as docile pets, expendable tools, brutal predators, cringing prey, or destructive pests—beings who, in all cases, are either servile underlings we feel entitled to dominate or encroaching aggressors we feel entitled to destroy—we can envision them as potentially flourishing creatures free to pursue ends uniquely their own.

We must achieve heightened awareness of the complex worlds and awe-inspiring capabilities that dignify other creatures and explode our comparative, inaccurate, and ultimately oppressive conceptions of them as subhuman. Because of our collective history of oppressing animals—and indeed, weaponizing the very idea of “the animal” to facilitate the oppression of fellow human beings—it is unsurprising and even fitting that our aspirations to go vegan often begin in lament over the cruel treatment of victims of this oppression. But going vegan can progressively lift us into heightened consciousness of members of other species as creatures whose lives are their own to cherish, beautiful in themselves and alive to possibilities we can never experience even as they provoke our deepest awe and respect.

“Animal consciousness” may sound a little spooky, but I think most of us have ample experience with what I have in mind. Just think of it as the felt human awareness that other animals have personal lives— that they are creatures who, like us, must make their own way in a world that pushes back. To have animal consciousness is to understand at some level, even if only occasionally in inklings, that other animals have lives that matter to them, lives that could be better or could be worse from their own perspective. Such creatures have experiences, desires, abilities to seek things they want and avoid things they dislike, and their desires are often personally inflected. Some dogs eat six pounds of carrots a week while others never touch the stuff.

But all dogs are cognitively, emotionally, socially, and physically invested in doing well for themselves, as their gorgeously shameless trash-rummaging, pre-vacation pouting, backyard showboating, and massage-begging ways attest. Animal consciousness comes in degrees and waxes and wanes situationally in keeping with how presently threatening or invigorating one finds the prospect that human beings are not the only creatures on the planet who cherish doing well. As children, many of us enjoy such high levels of animal consciousness that our fierce caring for the feathered and furry extends even to our stuffed animals (as any unlucky parent who accidentally smothers a plush sloth at bedtime is abruptly reminded). As we age, sustaining such high levels of animal consciousness becomes increasingly inconvenient, as our perceived interests in doing well come increasingly into conflict with those of other animals.

To the extent that our well-being seems to depend on steaks, chops, milk, and eggs, our animal consciousness contracts to the point of seeing animals, if we see them at all, as instinct-driven ambulatory objects ready to serve as tools for human use. But when a squirrel darts in front of the car or a tufted titmouse careens into the house, our consciousness intuitively if temporarily expands to receive these creatures as having interests in striving and surviving that soccer balls and paper planes clearly lack. And every now and then, when a mother mallard emerges from the brush with ducklings in tow, or a family of raccoons crests the garage roof on a moonlit quest for ripening grapes, our animal consciousness can instantaneously dilate into capacious curiosity, wonder, or even awe at their strivings. Most of us have it in us to be dazzled by other animals, at least when their flourishing demands nothing of us. In thrall to this bedazzlement, we can’t help but wish our fellow creatures well.

Excerpted from Hungry Beautiful Animals: The Joyful Case for Going Vegan by Matthew Halteman. Copyright © 2024. Available from Basic Books, an imprint of Hachette Book Group, Inc.