UK Farmers Recognise Potential Benefits of Cultivated Meat, Shows Government-Funded Report

7 Mins Read

Farmers have always been pitted against cultivated meat, but a new report suggests that despite concerns, they recognise the opportunities presented by these proteins.

When Italy, Florida and Alabama announced their respective bans on cultivated meat over the last eight months, the dominant rhetoric was that of protecting farmers and the cattle industry. Florida governor Ron DeSantis was very on-the-nose about it, standing behind a banner reading ‘Save Our Beef’ when signing the bill.

But critics quickly called out such moves as “protectionist” policies that served “entrenched interests”. They also pointed out the hypocritical nature of the farmer-friendly messaging used to justify the bans.

“This legislation has always been about one thing – helping one industry, Big Ag, avoid accountability and competition,” Tom Rossmeissl, head of global marketing at Eat Just, one of only two companies approved to sell cultivated meat in the US, told Green Queen after Florida’s ban became official. “Today, these multinational corporations and their lobbyists won.”

While you could argue that this response is expected from a company with interests in this novel food sector, what would you say if you found out that farmers – the very people these legislators claim to want to protect – themselves exhibited a similar concern?

In the UK, at least, farmers seem to be more worried about social issues brought on by cultivated meat – like Big Food controlling the market or the knock-on effects on rural communities – than its impact on the bottom line. And when pitted against changing weather patterns and global commodity markets, the threat of competition from cultivated meat feels like a “slow burn” to them.

This is according to research led by the Royal Agricultural University (RAU), which discussed cultivated meat with 80 farmers and nine farms to explore how they’d need to adapt their businesses in a future with cultivated meat.

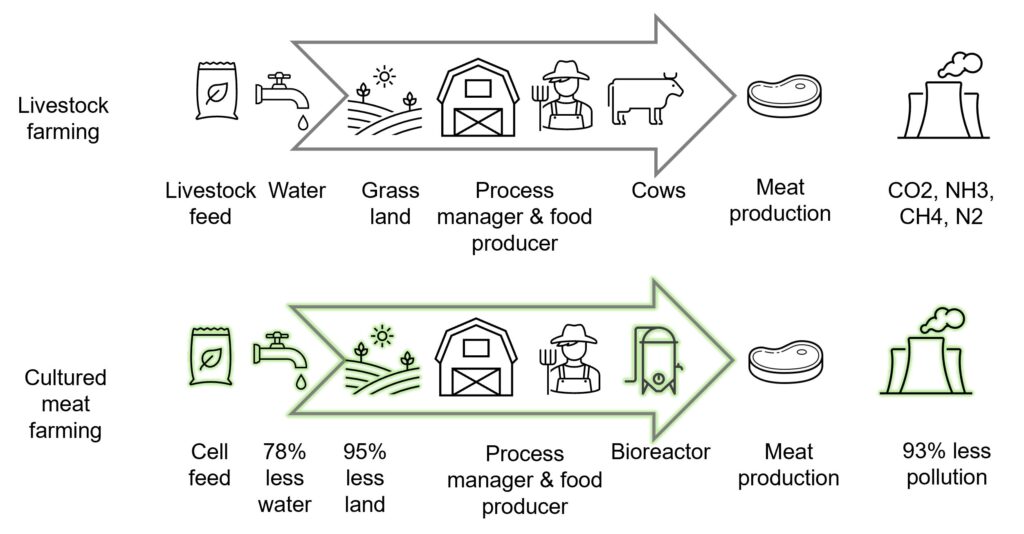

Backed by the Transforming UK Food Systems’s Strategic Priorities Fund (under the government body UK Research and Innovation), the takeaway was a potential win for the alternative protein industry, suggesting that farmers could help the sector grow and lower its environmental impact – and vice-versa.

“They certainly had a lot of concerns, but were also mostly willing to engage in discussion about potential opportunities,” acknowledged study lead Tom MacMillan, who is the Elizabeth Creak Chair in rural policy and strategy at the RAU.

“The message from our research is not [that] farmers are unconcerned, but that this doesn’t have to be a polarised debate, and there is potential for cultured meat businesses, farmers and other stakeholders to find synergies and shape the direction of this technology together,” he told Green Queen.

What are farmers’ biggest concerns about cultivated meat?

Most of the farmers RAU spoke to reacted first as customers instead of producers, echoing public concerns over whether cultivated meat is safe, natural and healthy, who is in control, and who really benefits from it.

But looking at it through a business lens, there were several worries. The industry’s future is shrouded in uncertainty, with farmers raising questions about cost competitiveness, quality and timeline to market launch, as well as whether it is meant to compete with processed or premium meats, or supplement meat-eating.

British farmers further expressed apprehension about the unreliability of data on the technical viability, economics, and climate and health impacts of cultivated meat, calling for impartial, more transparent information. There were also concerns about the unintended effects on their business or the local community, and the overall impact of these foods.

Some called cultivated meat an unrealistic proposition, citing a lack of attention on the supply chain and on how the “assumed effects on diets or land use” would be realised practically. Others echoed the rhetoric of lawmakers questioning the authenticity and naturalness of these meats, calling it “Frankenstein food”.

Additionally, a common concern related to the beneficiaries of cultivated meat. Does this really support farmers and the public, or just line the pockets of Big Food companies? The fear was that this could intensify the industrialisation and ‘Americanisation’ of food production.

“I do wonder if [with] the production of more… cultured protein, there are going to be much larger companies that are going to… be pushing for this and they will own the intellectual property, they will own the rights to that, they will own the formulations, and that’s something which reinforces a sort of a hegemonic position,” one farmer said.

“The farmers who spoke to us were most concerned about the wider social implications – for example, corporate concentration in food systems, health, and food culture,” said MacMillan. “However, they also highlighted potential unintended consequences that were thrown into relief by their direct experiences of food production.”

How cultivated meat could open up opportunities for farmers

“The nine UK farmers we spoke to in most detail had misgivings about cultured meat, but also faced other bigger challenges or felt fairly resilient, so the technology was not seen as a major business risk by most,” recalled MacMillan. “Several were interested in potential opportunities.”

These are wide-ranging, from supplying inputs and valorising waste streams to building supply chain relationships and harnessing private investment.

For example, farms can supply animal cells as well as food-grade ingredients (like glucose, amino acids and growth factors) for cultivated meat production. And they could do so by repurposing existing crops – such as feed wheat for glucose, rapeseed oil meal for amino acids, and plant extracts for 3D scaffolds – or incorporating new ones into rotation.

Even slaughterhouse byproducts like blood, hooves and horns contain elements that can be used as growth factors and media. This is an important consideration given that “hardly anyone” the RAU spoke to said they’d give up caring for their livestock altogether and make cultivated meat their sole business.

Embracing cultivated meat gives farmers a chance to review their agreements with intermediaries and overhaul the unfair distribution of power found in dairy and poultry supply chains. Plus, they can develop farmer cooperatives to supply ingredients, and even use private investment to produce cultivated meat. On-farm production could present options for direct sale and open up new markets and supply chains.

“The potential opportunities depended heavily on the type and location of a farm and its current business,” explained MacMillan. “Crop and fruit farmers were interested in new markets supplying raw materials. Some livestock farmers saw [the] potential to have higher-value, lower-volume sales, or to repurpose buildings or renewable energy for on-farm cultured meat production.”

The nine farms in focus were asked what they think their businesses would be like in 10 years if they continued business as usual, and if they incorporated cultivated meat. Across metrics like income, jobs, production, waste, biodiversity and climate, most had similar responses to both scenarios – and with cultivated meat, some aspects could be improved upon.

It’s significant because it means farmers don’t think cultivated meat would necessarily make things worse in the longer term. MacMillan, however, cautioned against viewing this pragmatism as a suggestion that farmers think cultivated meat would play a “substantial positive role” in maintaining or improving their businesses. “It is more that some [are] curious, and all have bigger worries,” he stated.

Building common ground with farmers and cultivated meat companies

The RAU highlights the importance of moving away from the polarised debate around cultivated meat to find common ground between the industry and farmers.

There are multiple ways to do this. Much of the polarisation is fuelled by hype and sweeping statements about a radical shift in eating patterns and farming practices, but producers would appreciate a more nuanced conversation that acknowledges uncertainty and champions farm innovation.

Both sides have accused the other of making biased claims for or against cultivated meat using favourable studies. But if research were commissioned by groups including both agricultural and alternative protein organisations, it can breed more trust. Plus, using an ‘all or nothing’ approach can often paint farmers as the enemy, so it’s vital to explore synergies between cultivated meat and farmers.

The report suggests joint research and innovation can help bridge this gap. This would entail looking into waste valorisation, developing fairer supply chains for cultivated meat, and trialling decentralised production on farms – akin to what RESPECTfarms is doing in the Netherlands.

Some farmers were keen to engage further with cultivated meat producers, so developing mechanisms for dialogue is key. RAU is working with the UK Cellular Agriculture Manufacturing Hub) to build a platform to connect farmers with businesses and researchers, and will create a neutral guide to cultivated meat for farmers.

Moreover, investors are urged to require companies to commit to a ‘just transition’ for farmers within their ESG commitments, while startups are encouraged to engage farmers in their governance. “The main thing at this point is to make sure farmers are engaged in helping figure that out on an ongoing basis, so that’s something we recommend to companies and investors working in this space,” outlined MacMillan.

“Moving beyond the polarised debate we’ve seen in some countries over recent years could provide a ‘win-win’ – not only benefitting the cultivated meat sector but farmers themselves,” said Linus Pardoe, head of UK policy at the Good Food Institute Europe. “I welcome the report’s call for companies to find meaningful ways of engaging and collaborating with farmers, while remaining sensitive to the uncertainties some farmers have about cultivated meat.”