Why Are We Still Killing Horseshoe Crabs? An Alternative Has Existed for Decades

6 Mins Read

The US Pharmacopeia has finally released draft guidelines to allow the use of human-made alternatives to horseshoe crab blood – a critical element in biomedical and pharmaceutical testing. After failing in 2020, can the guidance pass this time around?

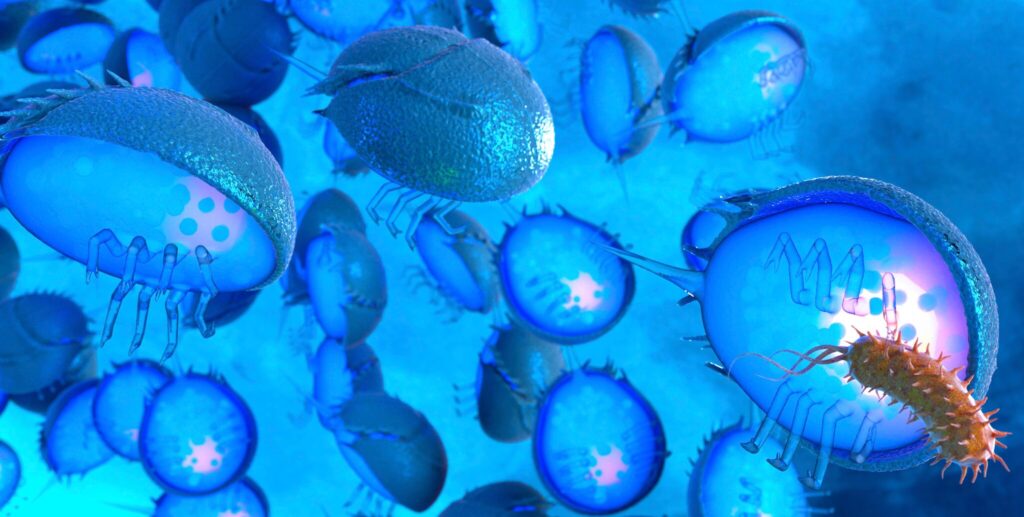

They have been around for over 450 million years, with their eggs being a major food source for coastal birds and certain fish species. They’re also known for their bright-blue blood – thanks to the presence of a tiny amount of copper – whose functionality has meant one of the world’s oldest species is now vulnerable.

I’m talking, of course, about horseshoe crabs. Over the last 50 or so years, humans have drained these sea creatures alive – quite literally. That blue blood is considered a vital source for endotoxin testing – it contains important immune cells that are highly sensitive to toxic bacteria. These cells clot around the bacteria to protect the rest of the horseshoe crab’s body from toxins.

Scientists have made use of this functionality by developing a process called limulus amoebocyte lysate (LAL), which tests new human vaccines for bacterial contamination. But this process, of course, involves taking horseshoe crabs, stabbing them in their hearts, and pumping out their blood (sometimes for as long as eight minutes, depleting half the volume of their blood).

However, for decades now, there has been a synthetic, man-made alternative to LAL – and yet, despite their importance to biodiversity, our planet’s history, and the overall ecosystem, the pharmaceutical industry has continued to use horseshoe crabs for vaccine testing. That, at long last, may change soon.

Why alternatives to horseshoe crab blood are important

There are four remaining species of horseshoe crabs, three of which are in Asia. The fourth, Limulus polyphemus, reside near the east coast of North America, and it’s these crabs that are under the spotlight, with the US Pharmacopeia – a non-profit regulatory body in charge of setting national safety standards (independent of the FDA) – publishing draft guidelines in August that will enable the use of synthetic alternatives to LAL.

Each year, around 80 million tests are performed using horseshoe crabs around the world, but within the US, just five companies along the East Coast, drained blood from over 700,000 crabs in 2021, according to NPR – that’s more than any other year since records began in 2004. And it is estimated that as many as 30% of these creatures die as a result of this bleeding process.

It’s not just the pharma industry – many around the world use these crabs as bait during fishing, as well as eat them as a delicacy. This has led to the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) declaring the American horseshoe crab as a vulnerable species. And in 2019 – along with other conservation groups – it called for stronger rules and more scientific research to protect horseshoe crabs.

These creatures are also crucial for biodiversity. Of the coastal boards that feed on its eggs, the most common is the red knot. These migratory birds rely on horseshoe crabs’ eggs to fuel their nearly 10,000-mile-long from South America to the Arctic every year. But around 94% of red knots have disappeared over the past 40 years, with the IUCN classifying the species as ‘near threatened’. A loss in horseshoe crab numbers would be fatal for these birds.

An alternative has existed for decades

The solution to the issue is an alternative that has been around for decades now. The problem, however, is its adoption. In the late 1990s, scientists at the National University of Singapore realised the potential a protein cloned from crab blood – called recombinant Factor C (rFC) – could have for endotoxin detection, sans animals.

Versions of this alternative have been produced by several biotech companies, including France’s bioMérieux and Switzerland’s Lonza. The latter’s rFC had initially been considered by USP to be added to guidelines that govern its international testing, but the effort was abandoned in 2020.

It meant that Big Pharma would continue to use horseshoe crabs for drug testing. USP’s decision came after Charles River Laboratories, a global biomedical giant that provides the pharma industry with over half of its LAL supply, criticised rFC citing safety concerns. Currently, USP’s rules put the synthetic alternative in a separate chapter in its guidelines, meaning that drug companies that want to use rFC need to conduct extra validation experiments.

It’s a heavily criticised move, given the LAL alternative has been commercially available since the 2000s. In 2019, the European Pharmacopoeia approved the use of rFC as an animal-free drug alternative. Around the same time, its Japanese and Chinese counterparts also approved the rFC test for use. In fact, as far back as 2012, the US FDA issued guidance on rFC testing for injectable medicines too.

Now, USP is finally coming on board. Its draft guidance – which is open for comment until the end of January – proposes changing its standards to support the use of synthetic alternatives to harvesting horseshoe crabs for blood. It advocates the use of not just rFC, but another alternative, recombinant cascade reagent (rCR), which contains rFC, recombinant Factor B, and a recombinant proclotting enzyme.

USP also details methods to use these synthetic reagents, as well as steps to verify their use for a specific product. Pharmaceutical companies producing new drugs can use the guidelines without needing to first show comparability LAL, but manufacturers of existing products looking to switch to animal-free testing are required to. However, switching from LAL remains optional.

“We acknowledge the need for information to help drive the adoption of recombinant reagents as alternatives to naturally sourced reagents from horseshoe crabs,” the group said in a statement. “This approach advances USP’s commitment to transition methods from using animal-derived materials to synthetic and recombinant materials.”

More wins for horseshoe crabs

The news around the same time environmental groups announced a settlement in a lawsuit against the South Carolina Department of Natural Resources and Charles River, alleging that they permit unlimited amounts of horseshoe crabs to be stored in ponds away from beaches. While the accused parties denied the charge, the settlement requires Charles River to provide for five years of enhanced protections for spawning horseshoe crabs and migrating red knots.

This means the company cannot harvest crabs across 30 island beaches, and is prohibited from keeping female crabs in ponds away from shores. It followed a ruling by the US Fish and Wildlife Service a few weeks earlier, which stated that harvesters can’t take crabs from their refuge anymore – this was the first time a federal agency acted in favour of horseshoe crab harvesting to protect red knots.

New Jersey congressman Frank Pallone welcomed USP’s new standards, which, “if adopted, will provide a viable alternative to the use of horseshoe crab blood in this process”. “Unfortunately, this global reliance on horseshoe crabs has placed an enormous strain on the population of these unique creatures,” he said. “I look forward to this new standard being finalised soon so that we can pave the way for more responsible medical options that do not rely on the vulnerable horseshoe crab population.”

Jaap Venema, the group’s chief science officer, said: “We hope that this will be an encouragement for companies to continue switching to non-animal-derived reagents. We’re only expanding opportunities for companies to start using them.”

The previous guidance in 2020 was thwarted after the public comment period – the hope is that this time will be different, allowing for animal-free testing to save human lives, while safeguarding horseshoe crab and red knot populations. It’s about time.