Climate Scientists: We Need to Halve Our Livestock Emissions by Replacing Meat & Dairy with Plant-Based Foods

6 Mins Read

Globally, greenhouse gas emissions from livestock farming must peak next year, and be reduced by 50% by 2030 to align with our climate goals, scientists suggest in a new survey. And to do this, we need to replace meat and dairy consumption with more plant-based foods.

To meet our climate goals, we need to stop eating so much meat and dairy, and start consuming more plant-based food, bringing the livestock sector’s emissions down by 61% by 2036, according to a survey of 210 global climate scientists and agrifood experts.

Carried out by researchers from Harvard University, New York University, Leiden University and Oregon State University, the report highlights the contribution of livestock farming to climate change, and the need to shift away from it, especially in high- and middle-income nations.

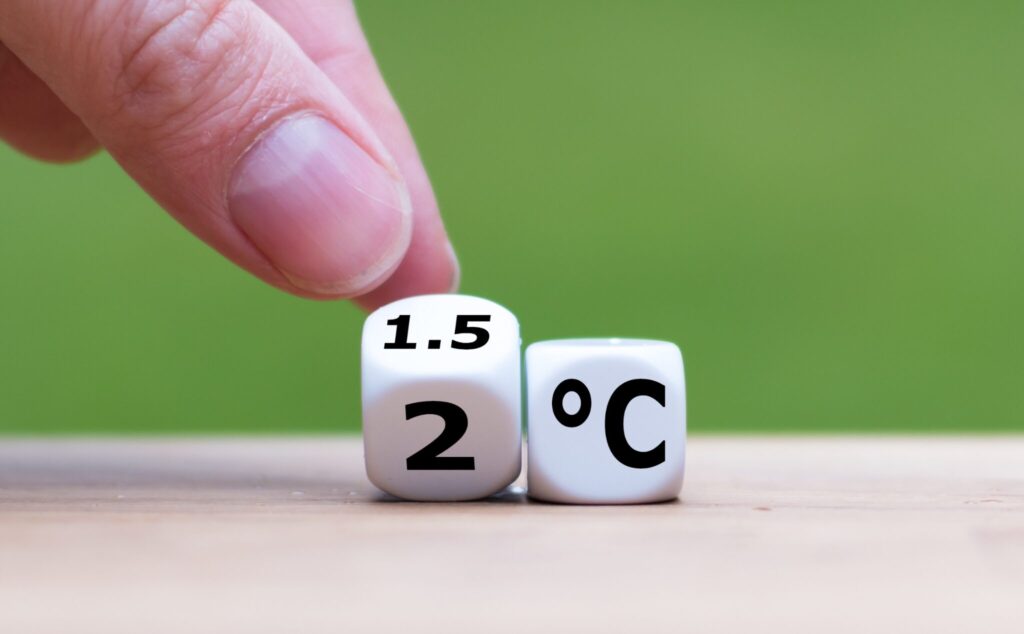

The food system accounts for a third of all greenhouse gas emissions, with meat responsible for 60% of that figure, despite only delivering 18% of calories and 37% of protein globally. At the current trajectory, the livestock sector is on track to taking almost 50% of our GHG budget in line with the 1.5°C postindustrial temperature rise goal. Plus, land use represents a quarter of emissions mitigation potential between now and 2050, and this industry occupies 78% of agricultural land and 39% of all habitable land.

The full implementation of all pledges to cut emissions under the Paris Agreement for 2030 aligns with a global temperature rise of 2.5°C this century, which will exacerbate the impact of climate change across the world, some of which will be irreversible. This is perhaps why 92% of experts agree that reducing livestock emissions is key to limiting temperature rises to 2°C, and 85% state that it’s important for human diets to shift from “livestock-derived foods to livestock replacement foods”.

“The report essentially provides the first articulation of a Paris-compliant livestock sector. The reduction targets for livestock suggested by the survey results are in line with what the IPCC show is needed globally for all emissions and sectors, so it appears that the experts are suggesting a reasonable pathway for the livestock sector,” said study lead Helen Harwatt, a food and climate policy fellow at Harvard Law School.

Plant-based products should be considered ‘best available foods’

Harwatt noted that this is not a one-size-fits-all approach, with different emissions reduction strategies outlined for countries with varying income levels. “High-producing and consuming countries must do the most the soonest, and have the most ability and potential to achieve this,” she said. “This doesn’t allow for high consuming nations to continue their ways by increasing imports from other countries while reducing their own farming emissions.”

The survey suggests that livestock emissions must peak in high-income (HICs) and middle-income countries (MICs) before 2025, but after 2030 in low-income nations. Over three-quarters (78%) also think global absolute livestock numbers should reach a peak by 2025. Following this peak, 89% and 75% of respondents believe these emissions should fall rapidly in HICs and MICs, respectively.

A majority (87%) of climate scientists and agrifood experts agree that all countries should have a GHG reduction target for animal agriculture in line with an overall emissions goal, with the most commonly agreed target being a 50% cut by 2030. In fact, respondents note that livestock emissions should be reduced as much as possible to reduce the risk of temperatures exceeding 1.5°C (87%) or 2°C (85%) by the end of the century.

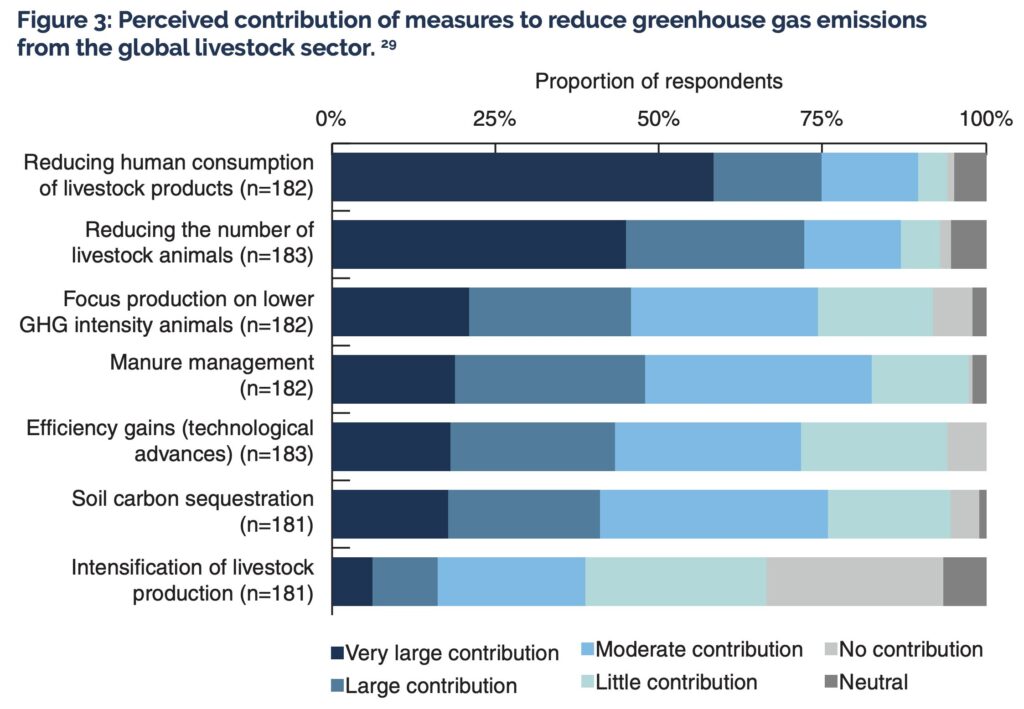

Eating fewer livestock-derived foods (like meat and dairy) and reducing the number of farmed animals were earmarked to be by far the most effective actions for GHG reduction, with about three-quarters of experts saying they have a large or very large contribution to emissions targets. The most substantial shift needs to occur in richer countries, with diets needing to shift from current patterns to “more plant-based” in MICs, and “much more plant-based” in HICs. In LICs, too, a slight shift to more plant-based eating is required.

The majority of experts say achieving these GHG reductions should not come at the cost of animal welfare – referring to a greater number of animals occupying a given space and increasing the confinement of animals. And most agree that where plant-sourced alternatives to animal foods provide comparable or better health outcomes and lower GHGs, they should be considered a ‘best available food’ and given preference in climate (83%), agriculture (78%) and food purchasing policies (82%).

Meanwhile, 82% think it’s important to restore carbon sinks and native vegetation cover on land currently occupied by the livestock sector, which could remove the equivalent of 16 years of global carbon emissions from the atmosphere over a 30-year period. Moreover, 76% of respondents say climate finance mechanisms, where required, should include assistance for farmers to transition their practices away from livestock production.

Climate policies are lacking – here’s what governments should do

The researchers outline that while we need to significantly reduce our livestock emissions to meet the goals of the 2015 Paris Agreement, country-level commitments to do so are severely lacking. “Much of the political focus has been on the energy transition; however, a food transition is also needed – especially for highly emitting animal products,” said Harwatt.

The report makes several recommendations for national climate policies to implement a livestock sector compliant with our emissions goals:

- Declare a peak livestock timeline: This would “ready the market” and enable suitable preparation by governments, businesses, investors and consumers. This time frame varies across countries with different incomes, as does the level of change required.

- Revise NDCs and prepare to meet other relevant pledges: This includes multilateral processes like the relevant targets for 2030 under the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework.

- Use finance streams for mitigation, adaptation and biodiversity: In HICs, this can incentivise the restoration of carbon sinks on land currently used for livestock agriculture, while in LICs, it could help implement more climate-resilient, low-carbon agriculture sectors, as well as help prevent further land use change.

- Align agricultural subsidies with climate goals: This involves taking a broader planetary health lens to ensure the maximum delivery of “public goods”.

- Invest in a plant-based transition: Financing agricultural alternatives to livestock for a transition to more plant-based food systems is key. This includes diversifying and increasing the production of pulses, and increasing R&D efforts.

- Undertake a national food system assessment: This is key to aligning policies and planning transitions to a livestock sector compliant with the Paris Agreement. It should include GHGs, land use, biodiversity and public health criteria, as well as the impacts of food and agricultural imports.

“How much and when livestock reduction should contribute to climate goals has until now been unclear – but these findings provide some clarity for policymakers grappling with these issues, and can help with the formation of plans to tackle climate change,” said Harwatt. “We’re way behind schedule on this, and technological solutions alone are inadequate. Difficult decisions are inevitable – and well-designed policy, communicated effectively, is essential.”