Grass-Fed Beef A Deceptive Climate ‘Solution’ That Misleads Consumers, Confirms New Study

5 Mins Read

Grass-fed beef is as bad for the planet as the industrial version, and significantly more carbon-intensive than plant proteins, a new study has found.

You may be eating grass-fed beef because you’ve been told it’s better for the climate. Turns out this claim is misleading “a large portion of the population who really do wish their purchasing decisions will reflect their values”, according to Gidon Eshel, an environmental physics professor at Bard College and the lead author of a new study lifting the curtain on the planetary impact of beef.

Proponents of grass-fed beef argue that it’s more environmentally friendly because cattle grazing can enhance soil carbon sequestration (offsetting production emissions in the process), but Eshel and his colleagues found that this wasn’t the case.

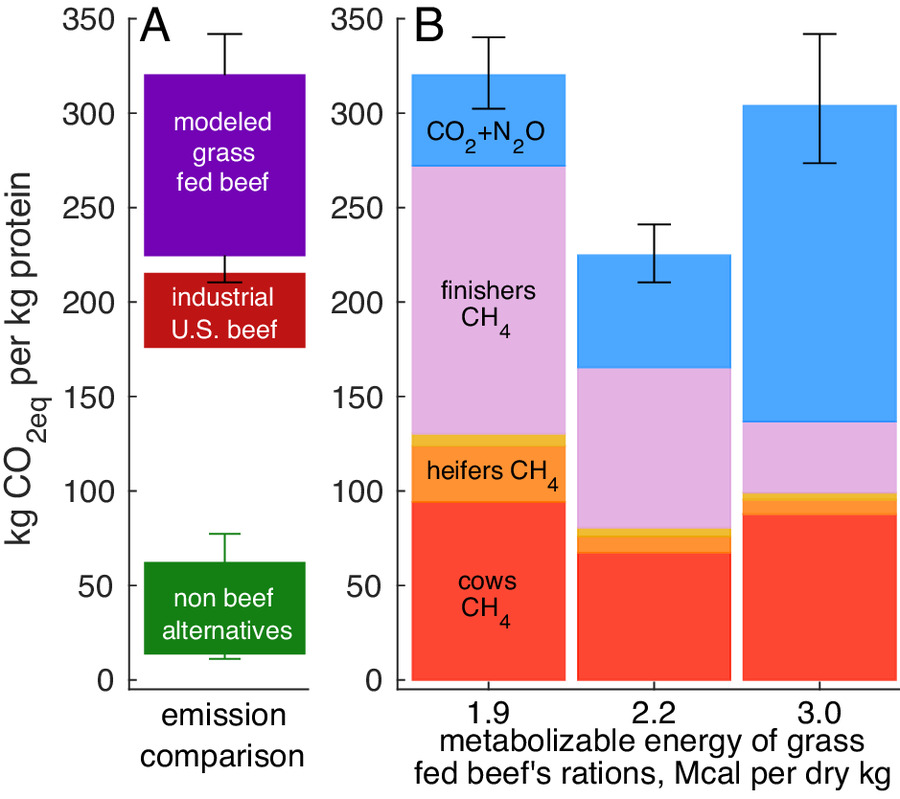

Published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences journal, their research suggests that beef derived from cows only raised on pastures does not present a climate benefit over grain-fed beef. Even the most efficient grass-fed operations had 10-25% higher emissions than industrially farmed beef. The former were also three to 40 times more carbon-intensive than proteins derived from plants or other animals.

In fact, replacing cropland-based beef with plant proteins is “far more environmentally lucrative”, according to the authors. While this is not the first study proving that grass-fed beef is a source of greenwashing rather than a climate solution, it’s still a damning indictment of the claim that any kind of beef is good for the planet.

Grass-fed beef is just as bad as industrial farming

Beef is the most polluting food on Earth, generating twice as many emissions as the second-worst product (dark chocolate). About half of these emissions come from methane, a harmful gas 80 times more potent than carbon over a 20-year period.

The average cow produces 200 lbs of methane a year – about half the emissions of an average car. According to the UN, cattle are responsible for over 60% of livestock emissions, which itself account for up to 20% of global greenhouse gas emissions.

In the US, only about 5% of cows are grass-fed, with the majority being raised in concentrated animal feeding operations (CAFOs), which are not just harmful to the animals, but also to human health and the planet.

Eshel and his colleagues used newly available estimates of beef cattle yields, herd methane production, and feed needs from across the US, and factored this data into a model that simulated and compared the emissions of grass-fed and industrial beef.

They incorporated estimates on the carbon uptake of grasslands into the model and excluded lush pasturelands with high rainfalls where other crops could be grown. This was done to align with the idea that cattle should only eat what humans cannot, and thus not take up land suitable for growing food crops.

The researchers found that grass-fed beef produces more emissions than industrial beef. While the carbon footprint of the former shrunk after factoring in the effects of soil carbon sequestration, it was still not low enough to position grass-fed beef as a better-for-the-planet solution.

This is because soil sequestration through grazing reduced grass-fed beef’s emissions from 280-390 kg of CO2e per kg of protein to 180-290 kg of CO2e, but industrial beef’s emissions were still at 180-220kg of CO2e.

“Accounting for soil sequestration lowers the emissions, and makes grass-fed beef more similar to industrial beef, but it does not under any circumstances make this beef desirable in terms of carbon balance,” Eshel told the Washington Post. “That argument does not hold.”

Swapping beef for plant proteins could bring large climate benefits

In stark contrast, non-beef alternatives generated 10-70 kg of CO2e per kg of protein, meaning that plant-based alternatives, pork, poultry, cheese and milk produced just 5-35% of the emissions of the least intensive grass-fed beef modelled in the study.

The researchers highlight how beef only contributes 5-20% of the calories from protein intake in the US, despite its production dominating the resource use in the food industry.

“Compared with non-beef alternatives, grass-fed beef yields at most one-tenth of the protein per kg CO2eq emitted regardless of agricultural intensity,” the study reads. “Beef – extensive, intensive, or anything in between – is not a competitive form of resource use.”

The authors argue that pasturelands should be rewilded to provide nature-based carbon sequestration and biodiversity benefits, as well as boost food security. Plant proteins can prove handy here – if 120 million hectares of semi-arid rangeland in the US were converted from beef to plant production, it would save annual emissions between 85 and 195 million tonnes of CO2e.

Likewise, croplands in high-rainfall areas can be repurposed from beef grazing to plant-based food for direct human consumption. Using only as much of these areas as required to replace protein from beef with plants would lower yearly emissions by 260 to 400 million tonnes of CO2e and free 50 to 120 million hectares of farmland.

Environmental journalist George Monbiot has famously railed against grass-fed beef advocates, calling pasture-fed meat production the “major cause of agricultural sprawl”. “The world’s urban areas occupy just 1% of the planet’s land surface, in comparison with the 26% used for grazing. Agricultural sprawl inflicts a very high ecological opportunity cost: the missing ecosystems that would otherwise exist,” he wrote in 2022.

“We live in a bubble of delusion about where our food comes from and how it is produced. We’ve been dealing in stories when we should be dealing in numbers,” he added.

The new study is especially relevant as it comes during the tenure of Robert F Kennedy Jr as US health secretary. He has previously laid out plans to shift away from intensive meat production and advocated for grass-fed, pasture-raised meat, despite limited evidence about the latter’s health benefits, and a trove of evidence finding it just as bad for the climate.

“I have a hard time imagining, even, a situation in which it will prove environmentally, genuinely wise, genuinely beneficial, to raise beef,” Eshel told the Associated Press. His advice for people who truly want to look after the planet? “Don’t make beef a habit.”