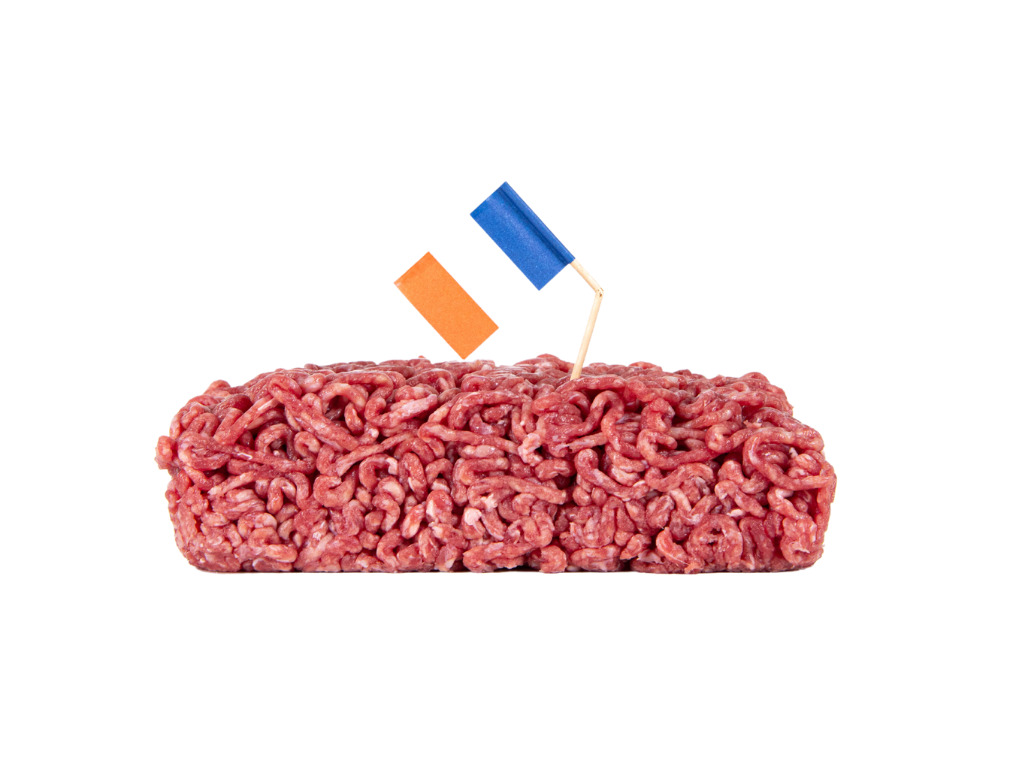

Sacré Beef: France’s Agriculture Ministry Proposes Labelling Ban for Plant-Based Meat Terms Like ‘Steak’, ‘Ham’ and ‘Grilled’

3 Mins Read

In the latest episode of a long-drawn saga, France’s agriculture ministry has drafted a new proposal to ban 21 terms like ‘steak’, ‘beef’, ‘ham’ and ‘grilled’ from plant-based meat labelling. The government has also listed over 120 meat-related terms that can be used only if products have a maximum share of vegan proteins between 0.5% to 6%.

With the proposed decree, France becomes the first EU country to attempt such a ban. But it isn’t the first time it’s tried to impose this. In June 2022, France decided to ban the use of meat-like terms in plant-based products, except for ‘burger’. “It will not be possible to use sector-specific terminology traditionally associated with meat and fish to designate products that do not belong to the animal world and which, in essence, are not comparable,” the decree read.

The proposed ban attracted controversy and criticism from meat-free groups. The European Vegetarian Union and the Association Végetarienne de France filed a complaint against the proposal, which was suspended by the Conseil d’État, the country’s highest administrative court, which argued the timeline was too short and the wording too vague.

Taking matters to the EU

Now, France’s agriculture ministry says it has taken the court’s complaints into account to prepare a new language decree, despite the court itself waiting for guidance from the European Court of Justice (ECJ) before making its final ruling. The ECJ has already protected dairy-related terms like ‘milk’, ‘cheese’ and ‘butter’ since 2017, preventing vegan brands from using them on their product labelling.

The new proposal, which is co-signed by French prime minister Elisabeth Borne, economy and finance minister Bruno Le Maire and agriculture minister Marc Fesneau, only applies to products made and sold in France. The draft has been submitted to the EU Commission for checking against its food labelling regulations. In 2020, the EU parliament voted against a proposed labelling ban on plant-based meat products, allowing vegan companies to market their alternatives as ‘burgers’ and ‘sausages’.

The decree has a list of over 120 meat-related terms like ‘bacon’, ‘sausage’, ‘cooked fillet’, ‘poultry’ and ‘nuggets’ (plus non-meat terms such as ‘liquid whole egg’) that companies can use, as long as the amount of plant protein in these products doesn’t exceed a maximum limit, which ranges from 0.5% to 6%. It essentially means vegan alternatives to such products won’t be able to be labelled this way, as all will contain 100% plant proteins.

“This new draft decree reflects our desire to put an end to misleading claims… by using names relating to meat products for foodstuffs that do not contain them,” Fesneau said. “It’s an issue of transparency and loyalty which meets a legitimate expectation of consumers and producers.”

Breaching EU regulation

Guillaume Hannotin, lawyer for the Proteines France organisation, which represents makers of vegan and vegetarian alternatives, said “the term ‘plant-based steak’ has been in use for more than 40 years”. He argued that the new decree still breaches EU regulation on labelling for products that – unlike milk – lack a strict legal definition and can be referred to by terms in popular use.

He added that the French government’s move “torpedoes the proceedings in progress before the ECJ”, which were triggered by a complaint from Proteines France itself.

France’s initial proposal last year came the same month South Africa’s agriculture department introduced strict labelling rules for plant-based food, banning all references to ‘meat’ and threatening to seize any products that fail to comply.

A report by ProVeg International last year found that there is no basis for claims of consumer confusion from the labelling of vegan products. 80% of respondents said that it was obvious that products labelled as ‘vegan’, ‘vegetarian’ and ‘plant-based’ don’t contain meat, while 76% actually found these labels helpful to understand and identify the nature of the product.