‘A Global Tragedy’: We Waste A Billion Meals Every Day, Just as 780 Million Go Hungry Globally

6 Mins Read

Despite more than 780 million people facing hunger around the world, over a billion household meals are thrown out every day, resulting in over $1T in economic losses, reveals a new UN report.

Households are discarding preposterous amounts of food every day, despite food waste being one of the largest drivers of food insecurity and global greenhouse gas emissions, according to the UNEP’s Food Waste Index Report 2024.

Whether it’s through poor planning, a lack of refrigeration or storage facilities, or just extravagance, about a fifth (19%) of all food goes to waste globally, amounting to 1.05 billion tonnes annually – and this excludes the 13% of food lost in the global supply chain (from rejection or spoilage, for example) in the post-harvest and pre-retail stages.

Co-authored with UK food waste charity WRAP, the report is an update on the 2021 index, aiming to provide accurate estimates on the scale of food wasted both at retail and consumer levels in 2022. It also explores how food waste differs across countries, and which of them have suitable reduction strategies in place.

“Food waste is a global tragedy. Millions will go hungry today as food is wasted across the world,” said UNEP executive director Inger Andersen. “Not only is this a major development issue, but the impacts of such unnecessary waste are causing substantial costs to the climate and nature.”

Households responsible for the highest amount of food waste

Of the total food wasted in 2022, households were responsible for 60% of it, totalling 631 million tonnes. Globally, we binned over a billion meals that year, which is described as a very conservative estimate. Each person wasted about 79kg of food on average, and the total is equivalent to 1.3 meals daily for every individual impacted by hunger around the world.

That said, the commercial food industry is responsible for a large part of this figure as well, with the foodservice sector responsible for 290 million tonnes (28%) and retail accounting for 131 million tonnes (12%). Overall, this costs the global economy $1T a year, just as 783 million people go hungry and a third of the population faces food insecurity.

The UNEP estimates that food waste contributes to 8-10% of global emissions – which is about five times the total emissions of the aviation industry – and displaces wildlife from intensive farming, with more than a quarter of agricultural land given over to the production of food that is eventually wasted.

This is why slashing food waste is crucial, with the 2022 Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework noting its link with biodiversity loss and outlining the goal to cut food waste by 50% by 2030. That is reminiscent of the UN’s Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 12, part of which lays out a target of halving per capita food waste across consumer and retail levels and reducing food loss across supply chains by the end of the decade. This goal itself plays an important role in delivering SDGs 2 (Zero Hunger), 11 (Sustainable Cities) and 13 (Climate Action).

Countries fail to highlight food waste in climate goals

With reliable data from over 100 countries, the Food Waste Index Report revealed that there isn’t a correlation between food waste and income levels, with the difference in food waste rates between lower- and higher-income households only 7kg less per person annually.

Hotter countries seem to have higher per capita food waste rates, which could be ascribed to an increased consumption of fresh food with more inedible parts, a lack of robust cold chain storage solutions, and the shorter shelf life of food in high temperatures. In fact, higher seasonal temperatures, extreme heat and drought present challenges to the safe storage, processing, transportation and sale of food, which also leads to significant volumes of food waste or loss.

The latter highlights the reciprocal relationship between food waste and the climate crisis. But only 21 countries – including Cabo Verde, China, Namibia, Sierra Leone, and the UAE – address food waste or loss reduction in their nationally determined contributions (NDCs) towards global climate goals. The upcoming revision in 2025 provides them with a key opportunity to integrate this into their NDCs. The UNEP suggests strengthening food waste reduction and circularity in cities, with rural areas generating less waste, as food scraps often go to pets, livestock, and home composting.

Only four G20 countries (Australia, Japan, the UK and the US) and the EU have food waste estimates suitable for tracking progress to 2030, with Canada and Saudi Arabia possessing suitable household estimates, and Brazil’s estimate expected later this year. These nations can play a huge role in global cooperation policy development to deliver SDGs, use their influence on consumer trends to promote awareness and education about food waste at home, and share their expertise with countries just beginning to tackle the issue.

“With the huge cost to the environment, society, and global economies caused by food waste, we need greater coordinated action across continents and supply chains,” said WRAP CEO Harriet Lamb. “We support UNEP in calling for more G20 countries to measure food waste and work towards SDG 12.3 [which concerns food waste and loss]. This is critical to ensuring food feeds people, not landfills.”

Public-private partnerships can help meet food waste targets

“We know if countries prioritise this issue, they can significantly reverse food loss and waste, reduce climate impacts and economic losses, and accelerate progress on global goals,” noted Andersen. In countries like the UK, Australia, Indonesia, Japan, Mexico and South Africa, food waste has actually been reduced significantly since 2007. In Japan, for example, food waste has declined by 31%, while the UK has seen it fall by 18%.

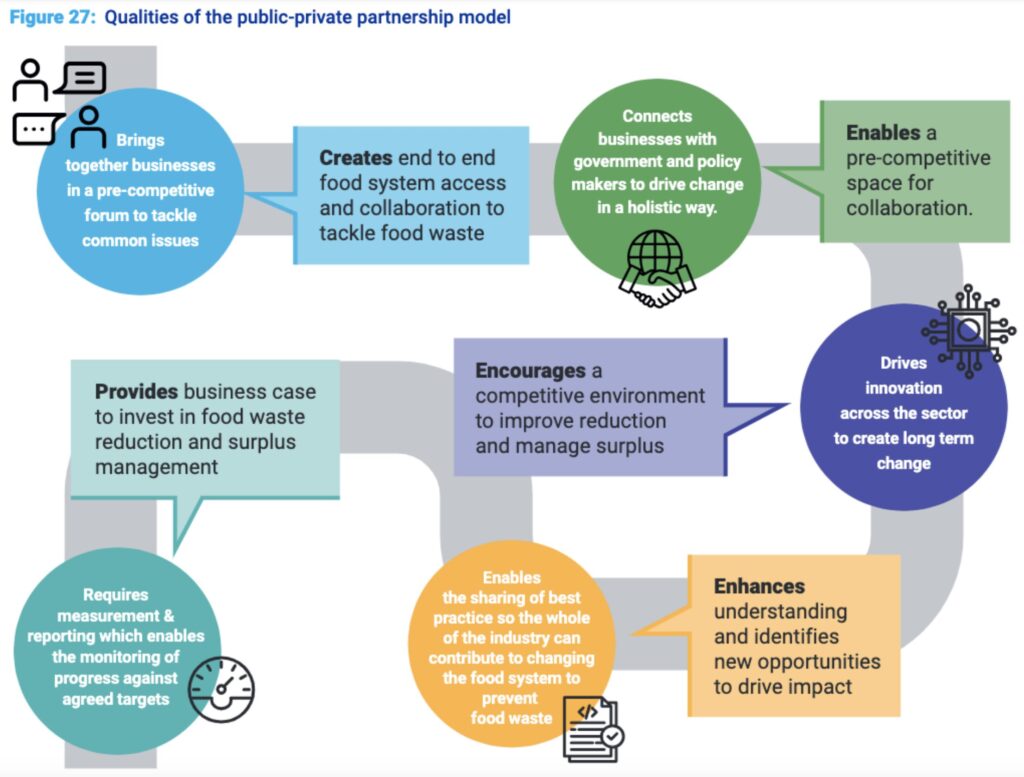

The report describes how governments, cities, municipalities and food businesses should work collaboratively to cut food waste and help households tackle the issue too. This is part of a larger approach around public-private partnerships, which the UNEP suggests can reduce food waste and its impact on climate and water stresses.

Centred around a five-step Target-Measure-Act strategy, these collaborations have already been embraced by a number of governments, including some of the aforementioned countries that have managed to reduce food waste. They bring stakeholders together to identify bottlenecks, co-develop solutions and drive progress towards a shared goal. “To take a collective approach is to recognise that no one actor can solve the problem alone, and that collaboration can create a movement that is more than the sum of its parts,” the report stated.

“Public-private partnerships are one key tool delivering results today, but they require support: whether philanthropic, business, or governmental, actors must rally behind programmes addressing the enormous impact wasting food has on food security, our climate, and our wallets,” said Lamb.

Some ongoing public-private partnerships around food waste include the UK’s Courtauld Commitment, Indonesia’s GRASP 2030, the US and Canada’s Pacific Coast Food Waste Commitment, South Africa’s Food Loss and Waste Initiative, and New Zealand’s Kai Commitment.