Climate Experts Develop Methodology for Food Banks to Measure & Reduce Methane Emissions

6 Mins Read

By diverting food waste, each food bank prevents as many emissions as 900 cars for a year, according to a new methodology designed to curb methane emissions.

The food system has a methane problem.

The greenhouse gas has contributed to 30% of global warming since the Industrial Revolution, and its presence in the atmosphere rose by 20% between 2000 and 2020. The 20-year period is significant: this is also the timeline in which methane is 86 times more potent than carbon dioxide.

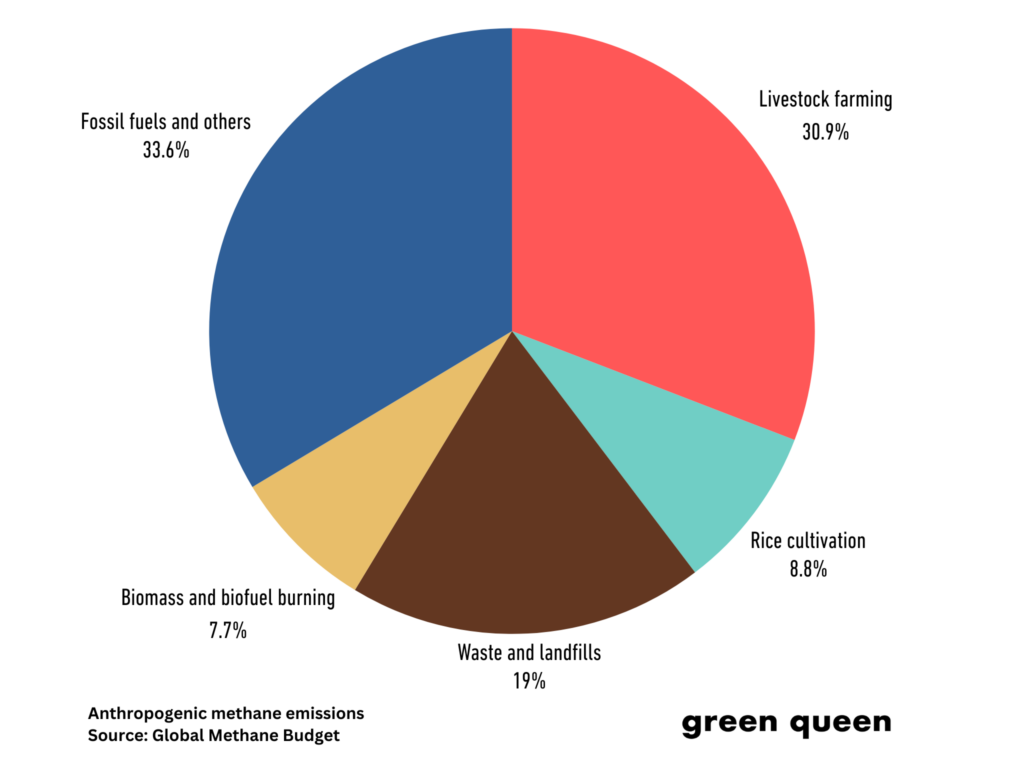

But unlike the outsized impact of fossil fuels on carbon emissions, the main source of methane is agriculture – mainly meat and dairy production. Farming accounts for 40% of human-caused methane emissions, followed by fossil fuels (over 30%).

However, there’s another major methane polluter: waste. Organic materials in landfills, wastewater, and food waste all combine to emit about a fifth of global methane emissions.

“Food, and any other organic matter, that is taken to landfill is typically buried under other waste, meaning that it decomposes without oxygen, or in anaerobic conditions,” Marcelo Mena, CEO of the Global Methane Hub, told Green Queen. “This results in the release of methane as bacteria break down the food waste.”

There are companies developing ways to lighten the methane impact of waste, but given that a third of all food is wasted or lost (amounting to 8-10% of global greenhouse gas emissions), there’s massive potential for food banks in this space.

This is why climate experts at the Global FoodBanking Network (GFN), the Global Methane Hub and the Carbon Trust have come together to develop a tool for food banks, food recovery organisations, as well as private-sector businesses to measure and reduce methane emissions from the food redistribution chain.

Piloting the FRAME (Food Recovery to Avoid Methane Emissions) Methodology in Mexico and Ecuador, the researchers revealed that six community-led food banks prevented a total of 816 tonnes of methane over a year by diverting food from landfills. That’s the equivalent of removing over 900 gas-powered cars from the road for a year, or the annual emissions from nearly 500 homes’ energy use, for each food bank.

How the food waste-methane methodology was developed

GFN argues that the methodology can enable food banks to help their countries achieve several of the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals, from Zero Hunger, Climate Action, and Responsible Consumption to Decent Work and Economic Growth.

“The main indicator for this methodology is the amount of methane emissions avoided,” said Ana Catalina Suárez Peña, senior strategy and innovation director at GFN. “However, indicators such as nutrients and energy contribution, full-time equivalent jobs, and total mass of food loss and waste redistributed were also considered.”

The development tool uses Microsoft Sustainability Manager, making it the first such use case for the software. This “adds further precision through preloaded data and standardised factors”, explained Fergal Byrne, senior analyst at the Carbon Trust.

“It builds on previous approaches to measure emissions by collecting additional data points, looking specifically at the reduction of surplus food, and accounting for additional operational activities to produce a highly credible and trusted outcome,” he said.

“The methodology dashboard generates and reports more than 100 indicators, which include methane emissions avoided as well as social impact indicators such as food recovered, people reached with redistributed food, and jobs created,” Byrne added.

“This allows food banks to provide a rigorous, comprehensive picture of the many benefits that food recovery and redistribution offers, from environmental sustainability to food security and community resilience.”

Suárez Peña said food banks are also using the methodology to better monitor and quantify emissions from their own operations, which has informed improved methane reduction plans. “On the other hand, this exercise has served as a driver for food banks to advance in their digitalisation,” she added. “As they also need better data, they must improve their information systems to collect and trace data, allowing them to also make better decisions.”

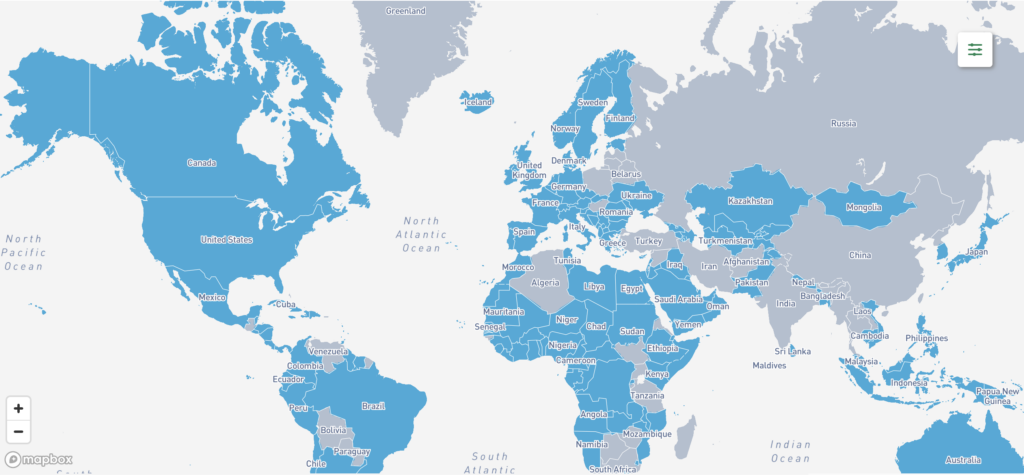

The methodology will support food banks in over 80 countries in reducing waste, mitigating emissions, and supporting national climate plans. The Global Methane Hub will back the next phase, which includes training on data collection at food banks in sub-Saharan Africa and Southeast Asia, as well as guidelines for policymakers and businesses alike on supporting food recovery and redistribution.

Governments have a ‘crucial role to play’ in methane reduction

Since methane has a major impact on the rate of global heating, efforts to reduce the gas’s presence in the atmosphere are imperative. “The good news is methane mitigation is the fastest and most efficient way to reduce global warming within a short timeframe,” said Mena from the Global Methane Hub.

“Because methane has a shorter life cycle than carbon dioxide, atmospheric methane could decrease dramatically in just 10 years if methane emissions declined,” he added. The UNEP has stated that anthropogenic methane emissions can be cut by 45% within the decade, which alone would avert nearly 0.3°C of temperature rises by 2045.

One such business is Brightly, which calculates methane emissions from the redistribution of surplus food from landfills to those in need, and converts them into high-integrity carbon credits for corporations to offset their emissions. “The majority of the revenue from these credits is returned to the food rescue organisations, empowering them to recover more food, feed more people, and reduce greenhouse gas emissions,” said Brightly founder Andy Levitt.

The voluntary carbon market is subject to heavy criticism as a tool of greenwashing, which Levitt said is warranted. “These bad projects undermine both the environment and the integrity of the carbon market, which relies on trust and legitimacy,” he noted, supporting the removal of such projects to boost the credibility of “genuine carbon credits like ours”.

In the US, too, food banks face unique challenges – those in food deserts need better access to fresh produce, while those in urban areas may struggle with reaching underserved communities. “Food banks need more than just food donations – they require financial and logistical support to sustain their operations effectively,” said Levitt.

“Governments, in particular, have a crucial role to play. By providing consistent funding and logistical assistance, they can help food banks expand their reach, improve infrastructure, and ensure a reliable flow of surplus food to those in need,” he added.

Globally, 158 countries have committed to cutting methane emissions by 30% come the end of the decade, as part of the Global Methane Pledge, although this effort is going in the opposite direction. One thing that will help governments is the new methodology, argued Suárez Peña, which would enable them to develop comprehensive policies on these issues.

“By integrating food banks’ work into Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs), governments can create financing schemes and tax incentives that promote food donation and waste prevention. They can enact laws reducing food disposal in landfills and allocate resources to social organizations for climate mitigation and adaptation efforts,” she said.

Policymakers are also urged to forge public-private partnerships. “By recognising the link between food systems and climate change, governments can create policies that simultaneously reduce food insecurity, curb methane emissions, and prepare vulnerable communities for climate impacts, ultimately contributing to national and global climate goals.”

For more on the link between food and methane, read our explainer.