Food Processing Facts: Big Food Defends UPFs with New Website

5 Mins Read

The Consumer Brands Association has launched a new website that aims to combat “consumer confusion” around ultra-processed foods – but context is crucial.

With ultra-processed foods (UPFs) taking centre stage in today’s dietary discourse, there’s a lot of information – and plenty of it misleading – around the health impacts of these products.

Today, in the US, UPFs make up 73% of the food supply and contribute to 60% of national calorie consumption. But many have begun rallying against these foods, with numerous studies linking them with ill health effects.

However, nutritionists themselves are at loggerheads about the correlation between food processing and nutrition – for many, one has nothing to do with the other.

UPFs continue to take a hit, though, with media coverage skewing mostly negative (at least when you glance at the headlines) and consumer perceptions souring. Even plant-based meats have been caught in the crossfire.

Who this hurts most is the world’s largest food companies, whose products line supermarkets and are the definition of UPFs. This is why the Consumer Brands Association (CBA) – an industry group whose members include the who’s who of Big Food – has launched a new website called Food Processing Facts.

“Our goal in creating Food Processing Facts is to shift the conversation past the clickbait headlines and create a trusted hub for information rooted in science, which paves the way toward a more constructive dialogue about food and nutrition,” says Sarah Gallo, senior VP of product policy and head of federal affairs at the CBA.

A chequered history

Before diving into what the website entails, it’s important to explore the context behind the CBA’s efforts. As an organisation, it has been around for over a century, but until 2020, it was called the Grocery Manufacturers Association (GMA).

This was the largest food and beverage trade group in the world – however, by the late 2010s, there was a lot of friction among its members, leading to behemoths like Unilever, Nestlé, the Campbell Soup Company and Kraft Heinz leaving the association.

The GMA was vehemently opposed to the labelling of GMOs on food packaging, and also fought back against efforts to require information about added sugar. While most of the defectors didn’t provide specific reasons for leaving, Campbell’s did: it opposed the GMA’s position on GMOs, and soon joined the Plant Based Foods Association.

The GMA rebranded to CBA and said it planned to focus more closely on consumer issues. Now, it represents over 2,000 brands and over 60 CPG companies. Nestlé, Campbell’s and Kraft Heinz have all returned, joining the likes of Coca-Cola, Danone, Ferrero, General Mills, PepsiCo, Kellanova, Nissin, and Mondelēz International, to name a few – all these companies make UPFs.

The CBA’s background is rooted in fighting for the big guy, and it’s worth keeping that in mind when scrolling through its new website.

Linking UPFs to health can be misguided

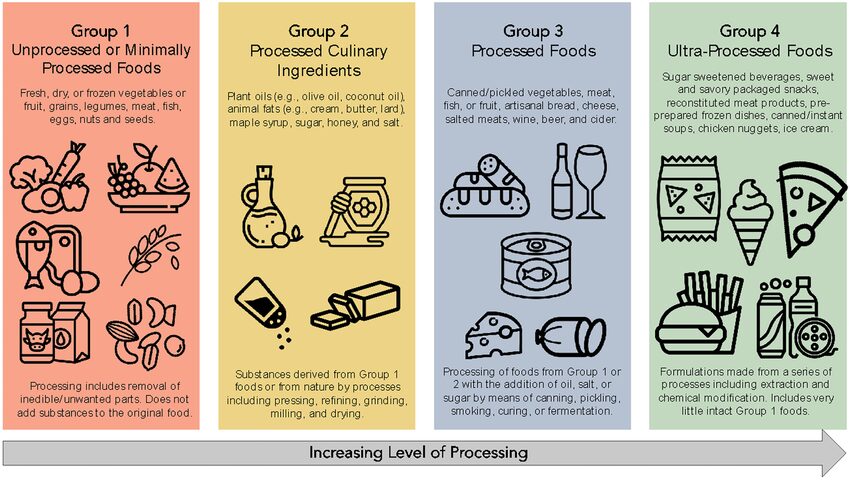

UPFs are part of the Nova classification, which places food into four subgroups, based on the amount of processing (nutrition doesn’t play a role in these categories). UPFs are at the bottom end of the ladder, consisting of industrial formulations and techniques like extrusion or pre-frying, and cosmetic substances like high-fructose corn syrup and hydrogenated oils

Broadly, this can include anything from ice creams, cereals and flavoured yoghurts to hot dogs, fizzy drinks, and plant-based meats. And that’s part of the issue: according to the Nova classification, tofu, yoghurt, Coke, and a packaged cupcake are all UPFs. But beer, cheese, cured meats and sugar don’t fall in the same category.

But this is by design. Jenny Chapman, a Churchill Fellow who authored a study about this topic, told Green Queen earlier this year: “The UPF category was never intended to group foods on the basis of nutrition, so it’s completely understandable that the category encompasses a wide variety of healthy and unhealthy foods, from crisps and chocolate, to infant formula, B12-rich oat milk and high-fibre plant-based meat.”

It’s a bit of a minefield, and even scientists disagree over the idea that just because a food is ultra-processed, it’s automatically bad for you.

“A study found only around 30% agreement on the placement of foods within Nova categories among food experts, suggesting the food categorisations used across studies almost certainly use different criteria for different foodstuffs,” Marlana Malerich, co-founder at the Rooted Research Collective and a food systems researcher with expertise in UPF, told Green Queen in June.

Who does Food Processing Facts truly serve?

Back to the Food Processing Facts website. “In the discussion about America’s food supply, many opinions have been shared without critical information and context, which are essential for consumers to form fact-based conclusions and make the right decisions for their families,” says Gallo from the CBA.

The website is described as a “one-stop resource dedicated to providing fact-based information and dispelling myths on food processing and safety”. It has a resource section that includes articles and studies that question the link between UPFs and health, alongside a news page with similar articles (with a few from CBA’s own website).

“‘Ultra-processed’ is not a science-based term. Using this subjective label to describe products as ‘bad’ due to level of processing will unnecessarily vilify certain foods,” one Did You Know? box says.

The website joins two other initiatives led by the CBA: Facts Up Front tackles on-pack nutrition information, and SmartLabel provides a QR code for detailed information not included in the Nutritional Facts panel. But both have their critics.

“The makers of America’s household brands are committed to providing convenient access to nutritious, affordable, and safe food and beverage products, and processing plays a critical role in delivering on this promise to consumers,” the CBA says.

One of its arguments in defence of UPFs is food security, something even scientists agree with. UPFs are cheap, and in a world where nearly 10% of people go hungry, they can play an important role. “We absolutely need foods to be processed so that we can feed the world,” Janet Cade, a member of the British Nutrition Foundation, said last year.

So while the conversation around UPFs absolutely needs to be more nuanced, whether the CBA’s new website aims to truly serve consumer interests, or – given its history – is just an effort to line the pockets of its members, remains unclear. Will consumers bite?