Breaking Down Fermentation Shaping The Alt Protein Industry: From Precision To Biomass

8 Mins Read

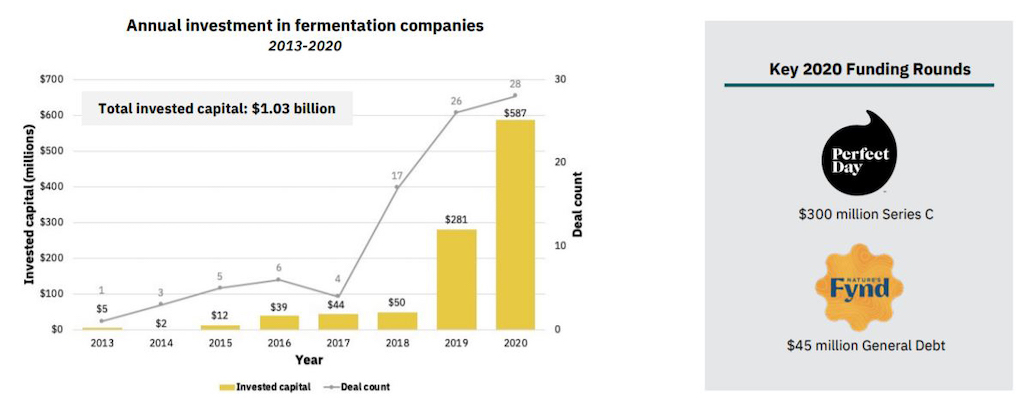

It’s everywhere. Impossible Foods, Perfect Day, MeliBio, Nature’s Fynd, Mighty Drinks — these are just a few of the dozens of companies championing fermentation to make greater strides in the alternative protein sector, particular when it comes to cheese, milk, and eggs. Founders and investors are hugely bullish.

In 2020, the Good Food Institute released a report calling fermentation the third pillar of alt-protein. Of the $1 billion raised by fermentation-based companies, more than half was invested in 2020 alone, with at least 51 such businesses focusing mainly on alternative proteins. But what exactly are we talking about?

It’s the ability to manipulate the flavour of an ingredient — and, in turn, the product it forms — to practically anything desirable is what makes it so attractive. Apply that principle to alternative proteins: imagine if you could find a way to use microbes, bacteria and common plant-derived ingredients and make them taste like meat, fish or dairy. The world would be your, well, fermented oyster.

There are three main types of fermentation at play when it comes to alt-protein: traditional, biomass and precision. Each is unique and has its own advantages. Below we break down each one and how it’s shaping the future of food.

Traditional fermentation

When we think of fermentation — the kind that’s been around for millennia — this is what we’re referring to. Dr Martin Wickham, director at Cambridge Food Science, explains: “In its simplest form, fermentation can be described as the chemical breakdown of a substance by bacteria, yeasts, or other microorganisms, to produce a beneficial compound, product, or a desirable attribute.”

It’s how we get bread, beer, yoghurt, wine, and cheese. Most homemade vegan cheese recipes, nut-based or otherwise, will employ one or multiple fermented ingredients — miso, nutritional yeast, apple cider vinegar, and so on.

But food scientists are constantly finding newer ways to use fermentation. Mirte Gosker, acting managing director of The Good Food Institute APAC, says fermentation is used in most vitamin supplements and fortified processed foods, like B12 and riboflavin. It’s also a base for many flavour components in the food we eat.

Now, traditional fermentation is being used as a tool, either exclusively or in tandem with other processes, to transform alternative protein. “Traditional fermentation can be used to improve the flavour or functionality of plant ingredients,” says Gosker, “as has historically been the case with tempeh.” Wickham adds that fermentation is “poised to revolutionise the food sector by accelerating the rise of alternative proteins”.

Biomass fermentation

Ever wonder how Quorn came up with its signature ingredient, mycoprotein, all those decades ago? Or how Nature’s Fynd turns geyser goo into plant-based meat and cheese? Or even how Mighty Drinks uses oats to create vegan milk closer to dairy? Answer: biomass fermentation.

“Biomass fermentation uses the high-protein content and rapid growth of microorganisms to efficiently make large amounts of protein-rich food,” explains Gosker. “In this application, the microorganisms that reproduce through this process are themselves ingredients for alternative proteins.”

Wickham expands on this theory, noting how it can take weeks and months to rear animals or grow plants using traditional methods of protein production, whereas you can potentially produce the same quantity of protein using biomass, or precise, fermentation in — brace yourself — a couple of hours.

“The microbial cells, or the biomass, produced can be either intact or minimally processed — cells can be broken open to improve digestibility or enrich for even higher protein content — and have a significantly high protein content of up to 50% by dry weight,” says Wickham. “This biomass serves as the main ingredient of a food product or as one of several primary ingredients in a blend.”

Quorn uses biomass fermentation to grow filamentous fungi and use it as a primary ingredient. Mighty Drinks ferments its oats — rather than microbes or fungi — via what the company terms ‘precise fermentation’* to manipulate the milk’s flavour.

Most companies utilise either solid-state fermentation, which is used primarily for biomass applications and includes growing microbes atop an inoculated solid surface, or submerged fermentation, common for both biomass and precision applications and where microbial cells are grown in a liquid medium. But Nature’s Fynd grows its biomass on top of a liquid surface, using liquid air interface fermentation technology.

Biomass fermentation also has the advantages of using considerably less land, water, and energy, as Wickham tells me, and producing a fraction of the greenhouse gases associated with traditional animal husbandry for the equivalent amount of protein.

Precision fermentation

While genetically modified organisms (GMO) aren’t common in traditional and biomass fermentation, they’re an ever-present fixture in precision fermentation.

Gosker says this method uses microorganisms to produce specific functional ingredients: “The microorganisms are programmed to be tiny production factories.” It’s how insulin is produced for diabetic patients is produced, and rennet for cheese. “It enables alternative protein producers to efficiently make specific proteins, enzymes, flavour molecules, vitamins, pigments, and fats.”

Companies like Perfect Day (dairy), Change Foods (cheese), The Every Company (eggs) and MeliBio (honey)— all headquartered in San Francisco — are among the pioneers in precision fermentation technology for a range of ingredients. In theory, you can create bio-identical animal proteins, like casein and whey, without using animals. Perhaps the most famous example of this technology is the Impossible Foods burger, which contains its flagship soy leghemoglobin (LegH), the iron-rich ‘heme’ protein that gives the company’s signature burger its meaty mouthfeel and its ‘bleed’.

“It is a type of biology that allows DNA sequences from a mammal to create alternative proteins,” explains Wickham. “These functional ingredients typically require greater purity than the primary protein ingredients and are incorporated at much lower levels. But even at these low levels, [they] can improve the sensory characteristics and functional attributes of plant-based products or cultivated meat.”

While this means you can, in theory, produce plant-based milk identical to its dairy counterpart or, in MeliBio’s case, flower-derived honey without bees, it also leaves a big gap in the allergen market. These animal-free products can still contain the same allergens present in their conventional equivalents. This means that Perfect Day’s plant-based milk, for example, isn’t dairy-free, despite not containing any animal products. It’s confusing, and so is the labelling.

What about labelling?

It’s been one of the biggest debates in the vegan industry over the last two years. Numerous hearings and court orders have passed on the terminology used on plant-based food labels. Is the term “veggie burgers” acceptable? Is “plant-based milk” fair? Does “vegan sausages” mislead consumers? And so on.

But microbial fermentation — along with cellular agriculture — poses the most challenging question of this discourse yet: how do you effectively label animal-free food that may not be allergen-free?

Technically, says Gosker, fermentation-enabled proteins are considered vegan, as they are not derived from animals. She adds that alt protein’s similarity to conventional protein is also the most appealing attribute for mainstream, non-vegan consumers. But that similarity also means people who could never eat, say, dairy products, can still not consume microbial-fermented dairy alternatives either. In fact, calling them an “alternative” might also be moot.

As Change Foods CMO Irina Gerry previously explained, “the discussion of whether or not these products are vegan-friendly or suitable for those following the vegan lifestyle is quite different from the discussion of whether they ought to be labeled vegan on their packaging. While consumers’ definition of veganism may evolve as more and more animal-free products come to market, educating consumers on precision fermentation technology and allergenicity of bio-identical dairy proteins is needed as we embark on this journey.”

That’s the challenge facing companies and regulatory authorities alike. But the priority, of course, is bringing all these different types of alt-proteins to market.

Impossible Foods has been using both traditional and precision fermentation to formulate its meat alternatives. Nature’s Fynd’s Fy protein-based meat products are already available in stores as of 2021 after gaining regulatory approval. And mycoprotein is no longer exclusively available via Quorn, with Sweden’s Mycorena one of many companies developing products with the biomass.

What’s next for fermentation?

But the highest-margin and most desirable segment of the $1.7 trillion global meat market are whole-cut products. And, according to Gosker, animal-free whole cuts and cutlets present a massive opportunity in the $2.2 billion alt-protein market. Colorado-based Meati is doing just that, utilising submerged fermentation to mimic the muscular structure of meat and develop whole-cut steak and chicken products.

Dairy is another promising application for fermentation. U.S. pioneer Perfect Day’s precision fermentation-enabled whey protein has already come to market, through a trial run at Starbucks and as an ingredient in Brave Robot’s ice cream and in Modern Kitchen’s cream cheese. Other notable players in the sector include Aussie-Californian Change Foods and Germany’s Formo. Eggs occupy the smallest, yet a growing, share in this sector. Fumi Ingredients has developed an egg white replacer that foams, gels and emulsifies, while The Every Company will launch the world’s first fermented egg proteins this year.

Wickham believes fermentation for alt-protein will become one of the world’s major food production methods within the next decade. Though it’s arguably already an unstoppable phenomenon, he adds, with its health impacts, contribution to climate change and a growing acceptance from regulatory authorities.

But perhaps fermentation’s biggest challenge is consumer acceptance. “The answer probably lies in future advances in our understanding of fermentation technology to produce protein that’s both tasty and at least on parity with traditional protein,” says Wickham.

Gosker adds that fermentation-based proteins are superior in “virtually every way” for people avoiding animal-based food for ethical or environmental reasons: “It’s simply a smarter way to make protein, full stop.”

Lead image courtesy of Perfect Day.