EU Directs Member States to Cut Food by 30%, But Climate Experts Lament ‘Weak Ambition’

6 Mins Read

The EU has set legally binding targets for all countries to reduce food waste by up to 30% in a revision of the waste framework directive, but climate groups say the target is not enough.

Lawmakers in the EU reached a provisional agreement that could help prevent millions of tonnes of food from ending up in the bin, marking the introduction of its first legally binding food waste reduction targets.

In an update to its waste framework directive, the EU Council and Parliament have directed all 27 member states to cut food waste by 30% from households, retail and foodservice, and by 10% in processing and manufacturing waste, against a baseline of 2021-23.

The agreement further states that voluntary donations of unsold food that’s safe for human consumption are an important aspect of food waste reduction.

While climate experts have welcomed the announcement of these first-of-a-kind targets, they have warned that these don’t go far enough. For one, they’re in direct contradiction to the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), which require cutting food waste across the entire supply chain in half by 2030. The EU committed to the SDGs a decade ago.

Shifting away from them is a sign of the EU “effectively planning to fail”, according to Martin Bowman, senior policy and campaigns manager at Feedback EU.

“The responsibility for this lies particularly with the Council of the EU for delaying negotiations then pushing for weak targets – but also with the Commission for limiting the terms of debate to low targets from the start, particularly for manufacturing and primary production,” he said.

“Still pending the final adoption of the text, policymakers in the European Parliament have sidelined the institution’s previous position on food waste targets after the political shift to the right,” said the Zero Waste Europe alliance, slamming the EU’s “weak ambition” and noting that most member states “strongly opposed stricter measures”.

EU leaders ‘shy away from decisive action’

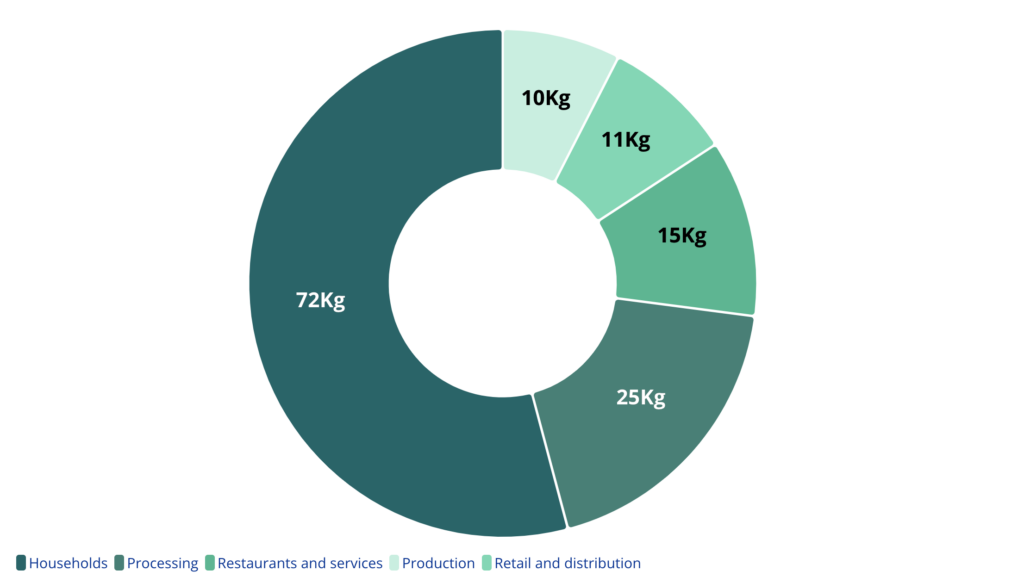

Each year, around 60 million tonnes of food goes to waste in the EU, amounting to 132kg per person. Of this, 545% comes from households, and 19% from the processing sector (warranting a reduction much greater than the 10% outlined by EU legislators). Retail and foodservice take up another 19%, while farms are responsible for the rest of the waste.

Collectively, this results in financial losses of up to €132B, and causes 16% of the EU’s greenhouse gas emissions, just as 33 million of its residents can’t afford a full meal every second day.

The revised waste framework directive, however, doesn’t take any action against food waste and loss at the production level, which contributes to 8% of all food waste in the region. And research has shown that fast reductions are possible in the processing sector.

“Now that it’s time to introduce binding targets, our leaders shy away from decisive action, ignoring the huge impact food waste has on climate change,” said Theresa Mörsen, waste and resources policy offer at Zero Waste Europe. “Ambitious and legally binding targets are an essential tool in bringing all countries and all food businesses on board in the fight against food waste.”

Some, however, had a different take. “Let’s not forget that these are the world’s first-ever legally binding targets, not just goals or aims which countries can easily miss,” noted Liz Goodwin, food waste director at the World Resources Institute. “The EU’s plan also provides for the voluntary donation of unsold food that is safe for human consumption as an important aspect of reducing food waste.”

She added: “Globally, there has been far too little government action on food loss and waste. Policymakers often overlook reducing food waste, despite it being a key strategy to bolster the food system, combat climate change, and save money. So this is a significant development that sets a new bar for action.”

Food waste policies ramping up globally

Bowman agreed that the legally binding targets were still a positive step. “Since 2030 is now only five years away, the 30% targets for households, retail and catering sectors will still be stretching for many member states – it will be essential for member states to rapidly develop action plans to unlock faster progress, drawing on regulations beyond just voluntary business measures,” he said.

The revision of the framework comes at a time when governments across the world are clamping down on food waste, as its impact on climate change and food security becomes starkly clear.

One of the EU’s member states, France, is a leader in food waste policy. In 2012, it put restrictions on the amount of organic waste that could be sent to landfill, mandating households to separate their organic waste so it can be composted or recycled into renewable energy. Four years later, the Garot Law banned supermarkets from destroying unsold food, instead directing retailers to donate food to charities where possible.

South Korea is another trailblazer in this space, which outlawed the disposal of food in landfills back in 2005. But a decade prior to that, it introduced a pay-as-you-throw system – based on the polluter pays principle, it instructed households and businesses to separate waste and dispose of it in special bags, for which they’re charged a collection and recycling fee based on weight.

In the Americas, Peru was the first non-European country to mandate food donation. And several states in the US have also introduced bans on food waste – to varying effects, according to one study. But the country did make major strides under the Biden administration, issuing its first nationwide policy to fight food waste and loss last summer.

Member states should view EU targets as a ‘floor’

The EU can take inspiration from these countries to introduce more stringent food waste legislation. A recent study by the Harvard Law School and the Global FoodBanking Network suggested that policymakers should emphasise waste prevention first, involve stakeholders at all stages, and employ a whole-of-government strategy to combat food loss more effectively.

According to Bowman, “more ambitious member states” should view the new binding targets “as a floor to their ambition” and still voluntarily aim to halve food waste across the value chain by 2030.

“Looking forward, it is essential for the EU to extend measurement to cover food unharvested on farms and include primary production in binding reduction targets, as otherwise food waste risks being pushed onto farmers,” he said.

Legislators have left open the possibility of setting targets for primary production in a review in 2029. But before that, the agreement needs to be confirmed by the EU Council and Parliament before it’s formally adopted. Once that happens, member states will have up to 20 months to update their national laws in line with the new rules.