Four in 10 Environmental Journalists Have Received Threats for Reporting on Climate Change: Survey

6 Mins Read

As the climate crisis worsens, so does the security of those who report on it, leading many journalists to censor themselves or use sceptics for ‘balance’, a new survey finds.

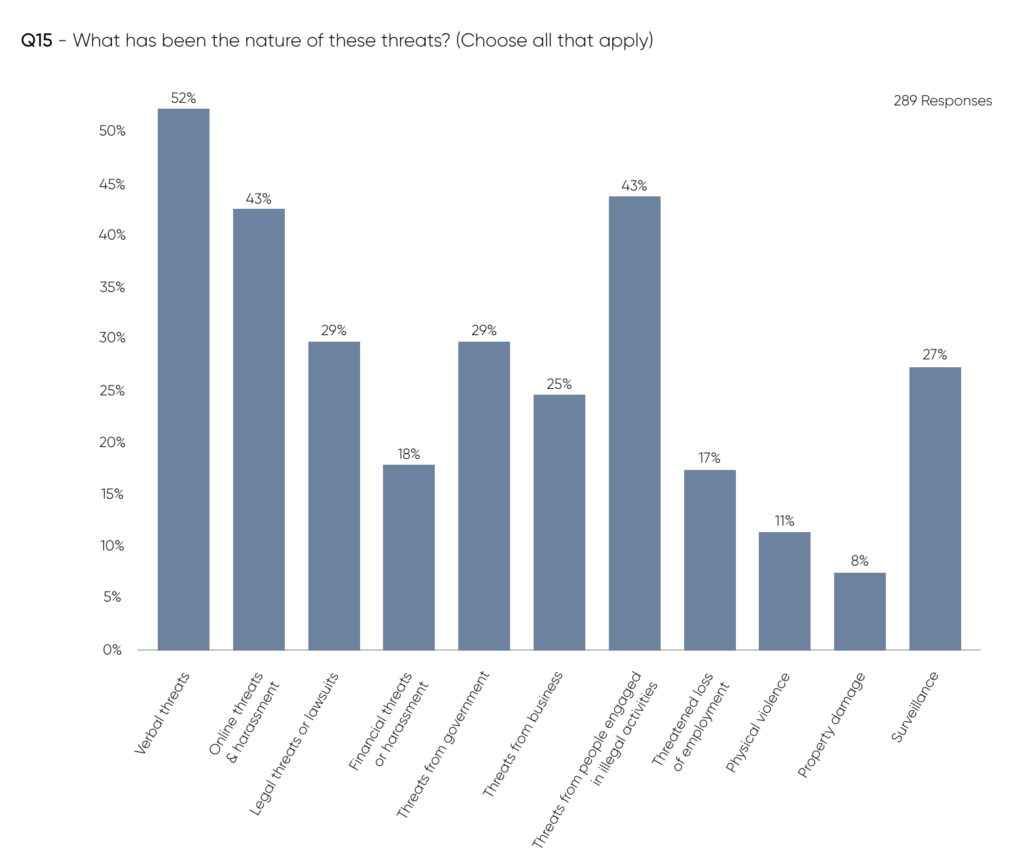

Nearly four in 10 journalists (39%) reporting on climate change and environmental issues have been threatened because of their work, with 11% facing physical violence and 8% subjected to property damage, reveals a damning new report.

The survey of over 744 journalists in 102 countries – carried out by Internews’ Earth Journalism Network (EJN) and Deakin University – revealed that while over half (52%) of these threats were verbal, 29% of them were legal threats or lawsuits. The majority of these came from people involved in illegal activities (43%) and via online harassment (also 43%). Meanwhile, 29% of threats to climate journalists came from governments.

Women have a higher chance of facing threats (64%) than men (59%). And this has led to 39% of climate reports censoring themselves, a trend that has increased for nearly half of respondents in the last decade. The two major causes that made them self-censor were people engaged in illegal activities (42%) and governments (41%). Public response has deterred 26%, and retribution from the owners of their media outlet has made 22% choose not to report on issues or change their approach to a story.

“The work of ‘covering the planet’ poses diverse challenges for journalists all around the world – but this work is urgent and vital,” said lead researcher Gabi Mocatta, from Deakin University. “Such insights are crucial in order to support and amplify the work of journalists who tell the most important stories of our times.”

The study comes at a time when climate journalism and press freedom face ever-increasing threats – at least 30 environmental reporters have been killed for their work since 2009. During a year when half the world is voting with climate change on the ballot, protecting them is more important than ever before.

Climate journalists grapple with objectivity

The majority of journalists (77%) said climate stories have become more prominent in the last decade, the main reason being the rise in environment-related issues (cited by 60%). Only 18% ascribed this to an increase in public interest, and even fewer (6%) said it was because of more frequent government briefings.

A similar number of respondents (82%) said reporting on climate change is treated as more important than other verticals from a decade ago. That said, many felt the volume of coverage is still not commensurate with the gravity of the climate crisis.

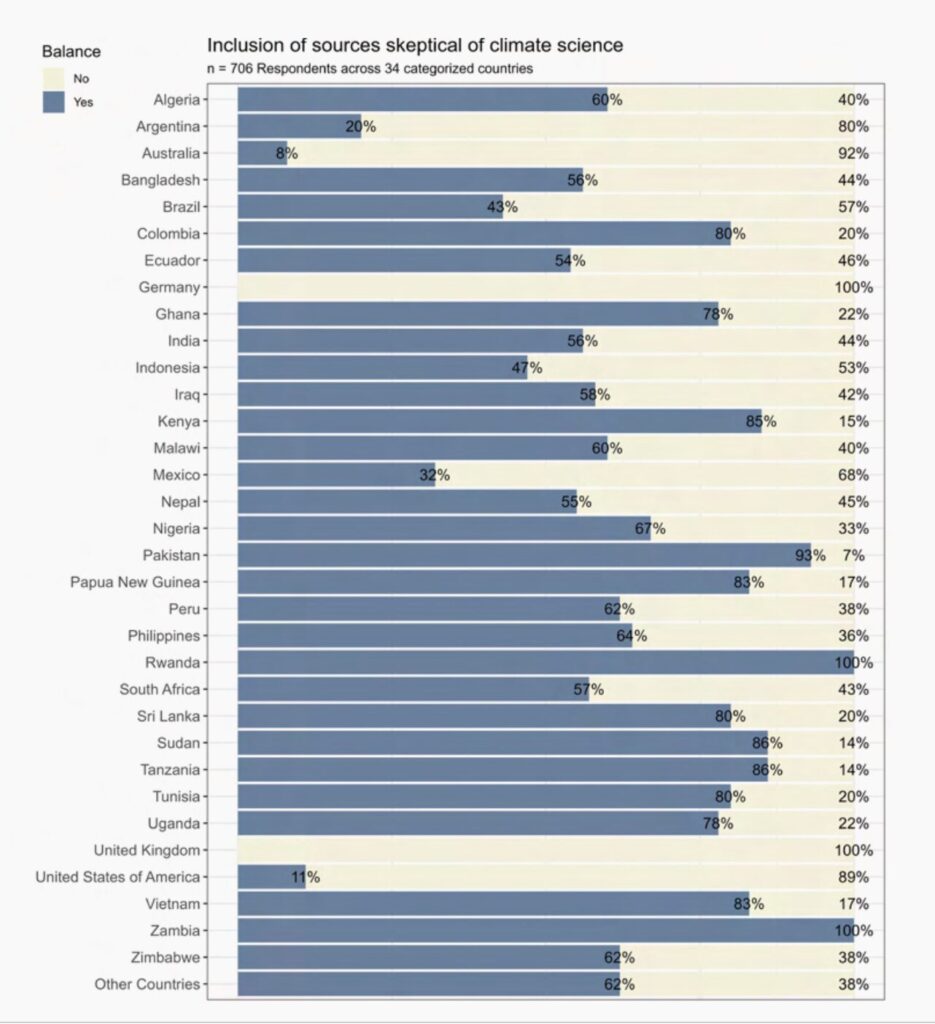

The concept of objectivity is divisive. Of the surveyed reporters, 62% said they include statements from climate sceptics – those who deny human-caused climate change – in the name of ‘balance’. But as part of detailed interviews with 74 journalists, the survey revealed that they depicted nuanced conceptions of objectivity versus advocacy.

Concepts of balance and objectivity remain challenging and divisive: 62% of respondents said they include statements from sources that deny human-caused climate change in the name of “balance.” Yet, in interviews, journalists demonstrated nuanced conceptions of what constitutes “objectivity” compared to “advocacy.”

This problem is most prevalent in Zambia and Rwanda (where 100% of respondents include climate-sceptic sources), followed by Pakistan (93%). On the other hand, none of the journalists from the UK and Germany said they add statements from such sources, a figure also low in Australia (8%) and the US (11%).

Misinformation and lack of funding holding back environmental reporting

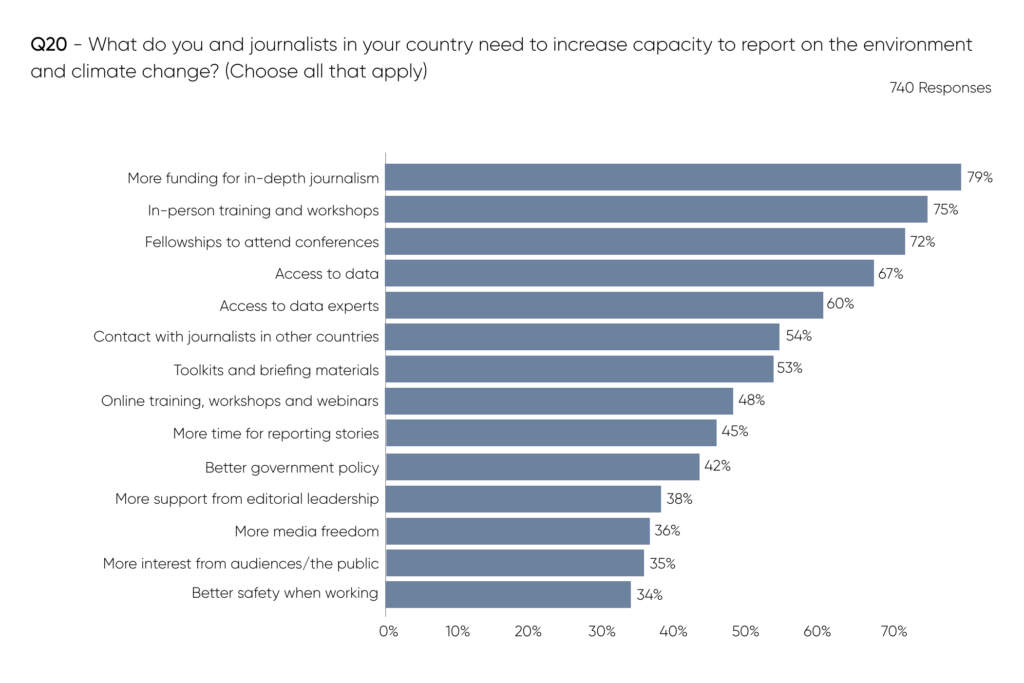

A lack of funding and resources is overwhelmingly the most limiting factor for climate journalists, with 76% citing it. Over a third of respondents also pinpointed a lack of public interest, while just under a quarter pointed to the danger of covering such issues. For a further 15%, the direction of their companies’ owners was a deterrent, while 12% felt advertiser preferences also limited their reporting of environmental stories.

In line with this, 79% of climate journalists believe their countries need to provide more funding for in-depth coverage of these issues, emerging as their biggest demand. Fellowships to attend conferences were also a highly popular need (72%), as was access to data (72%). Notably, 42% of respondents said they want better government policy.

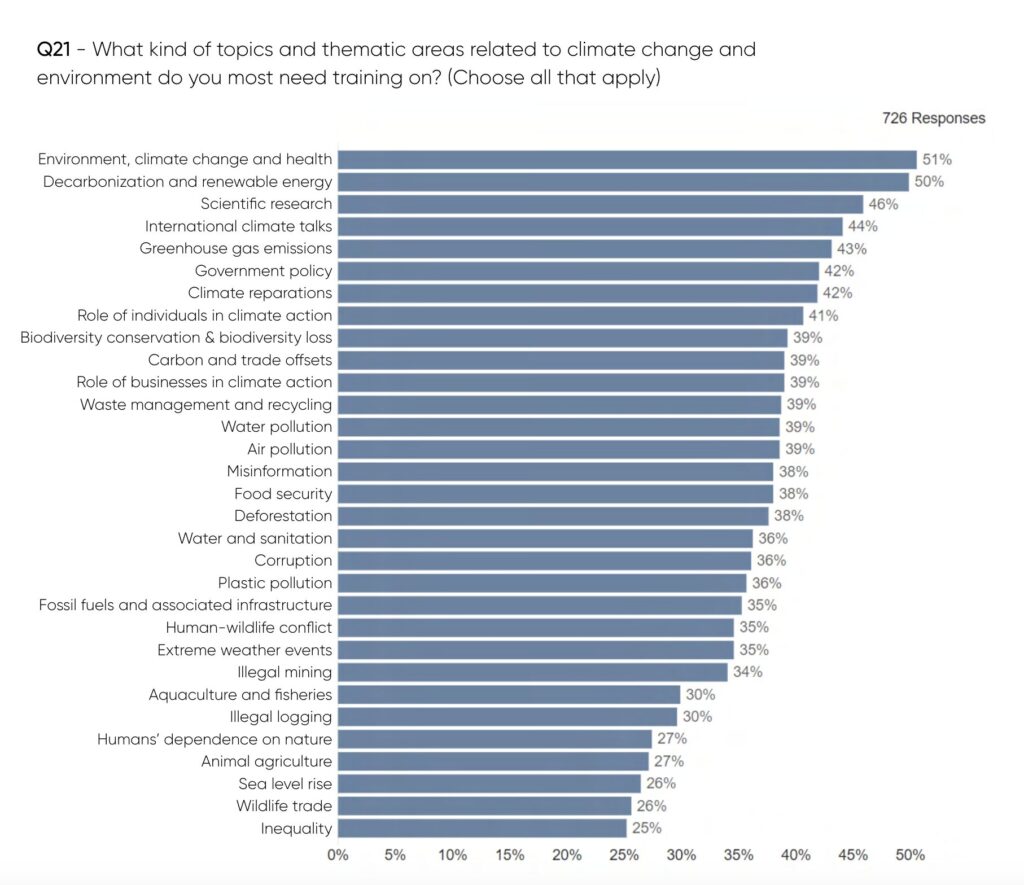

Meanwhile, a third spoke to a lack of expertise in the area as a reason they can’t report on climate change as much as they’d like. It makes sense, then, that three-quarters of journalists want more in-person training on climate issues.

When asked what themes such training should cover, half said environment and health, and decarbonisation and renewable energy, highlighting the gap between the impact of health and fossil fuel on climate change, and awareness about the same.

Interestingly, only 27% of reporters said they’d like more training on animal agriculture, which is responsible for up to 20% of all emissions, and a major driver of biodiversity loss and deforestation. But separate research has shown that 93% of climate stories don’t mention animal agriculture. “There are themes central to environmental and climate problems that journalists may still not cover frequently, and consequently, they may not feel the need to build expertise in these areas,” the EJN-Deakin report says.

Journalists also said misinformation is on the rise, with 58% suggesting it had increased in the last decade. And nearly half (46%) felt misinformation is “very much” or “extremely” undermining their work – only 11% said it didn’t affect their reporting at all. Social media posts were identified as the largest source (with 93% agreeing), followed by industry or private companies (42%) and government media (32%).

How we can help climate journalism

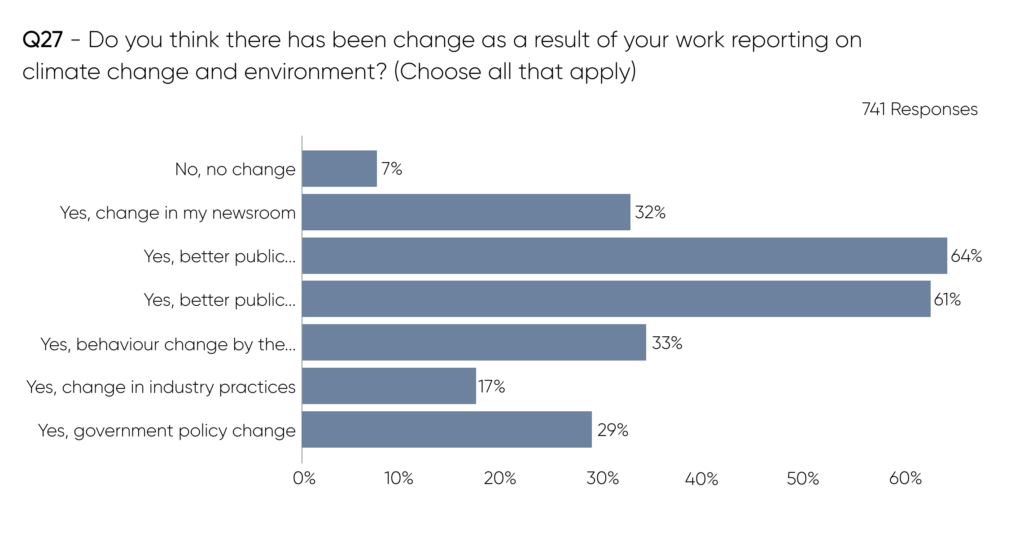

The survey asked reporters if they had witnessed any changes as a result of their work on climate change. Encouragingly, only 7% said it hasn’t had an impact. The biggest changes have been in public awareness of climate change and environmental issues (over 60%) – although this hasn’t translated to actual behavioural change on their part, something only 33% of journalists believed they have seen.

Meanwhile, 29% have seen changes in government policy and 17% in industry practices. “The journalists surveyed are steadfast in their dedication to reporting on how climate change and environmental crimes are negatively impacting both people and the planet – but they desperately need more support,” said James Fahn, executive director of the EJN.

So how can we do that? If you’re a funding organisation, the authors recommend you prioritise support for locally relevant stories and training opportunities, work with newsrooms on the longevity of funding, develop a nuanced approach to objectivity and advocacy, and avoid donor influence on climate coverage.

If you’re a newsroom, encourage reporters to specialise in climate change, broadcast more environmental stories, encourage collaboration and knowledge sharing, help journalists understand misinformation and how to avoid it, and protect their employees’ physical, legal and digital safety.

Finally, if you’re a journalist yourself, make global environmental stories locally relevant, cover both problems and solutions, and highlight climate justice in your reporting. Journalists should also consider their own position on the objectivity-advocacy spectrum, and they shouldn’t platform climate deniers. They must also build their knowledge on attribution science (linking extreme weather events to the climate crisis), and make clear humans’ dependence on the natural world.

After all, as the authors write, “all stories are climate stories”.