10 Mins Read

Precision fermentation, described as the third pillar of alt-protein alongside plant-based and cultivated foods, is on the rise. There are at least 62 companies working in this space globally across the supply chain, with a big focus on animal-free dairy proteins. How does this sector stack up with conventional milk in terms of its climate credentials?

The precision fermentation sector has raised about $3.7B in total funding, with over $840M coming in just last year, according to industry think tank the Good Food Institute, which refers to it as the third pillar of alternative protein. It’s a fast-growing sector – and one of its primary focuses is creating environmentally-friendlier alternatives to dairy.

The technology has been around for over 30 years but came into the spotlight after alt-dairy startups like Perfect Day burst onto the scene. In terms of animal-free milk, precision fermentation involves producing molecular identical dairy proteins like casein or whey by encoding milk protein DNA sequences into microorganisms like yeast or fungi. These are then fermented with nutrients and sugar in tanks akin to those that use beer.

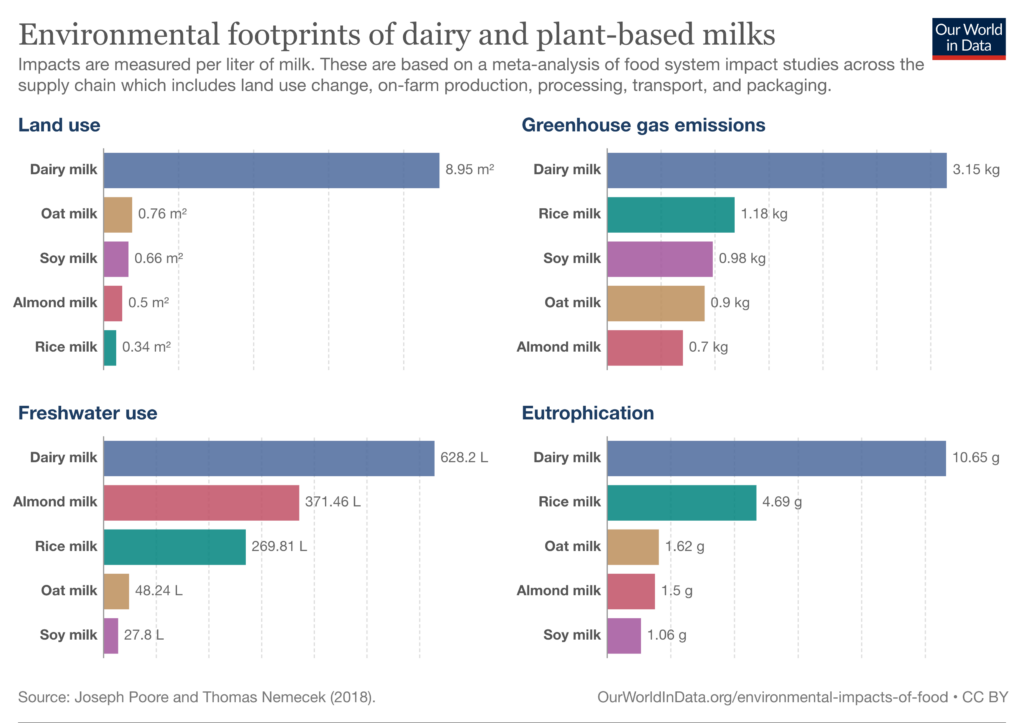

These microbes then produce proteins that are identical to traditional dairy proteins, which are then filtered into a pure milk protein isolate that can be used to create dairy products like cheese, yoghurt and ice cream without any animals. The animal welfare angle aside, there are numerous advantages of precision-fermented dairy, which is said to have a fraction of the carbon emissions and use much less land and water than conventional dairy.

While precision-fermented dairy makes up a fraction of the overall dairy sector, there is precedent for its future success. Insulin for diabetics used to be made from cow and pig pancreas, with the process requiring 50,000 slaughtered animals to produce just 1kg of the hormone. But now, 99% of the global insulin supply is made using precision fermentation. Meanwhile, 80% of the world’s rennet – a crucial ingredient for many cheeses that used to be exclusively sourced from the stomach lining of young cows and sheep – is made using this tech.

Perfect Day & Bon Vivant’s precision fermentation LCAs

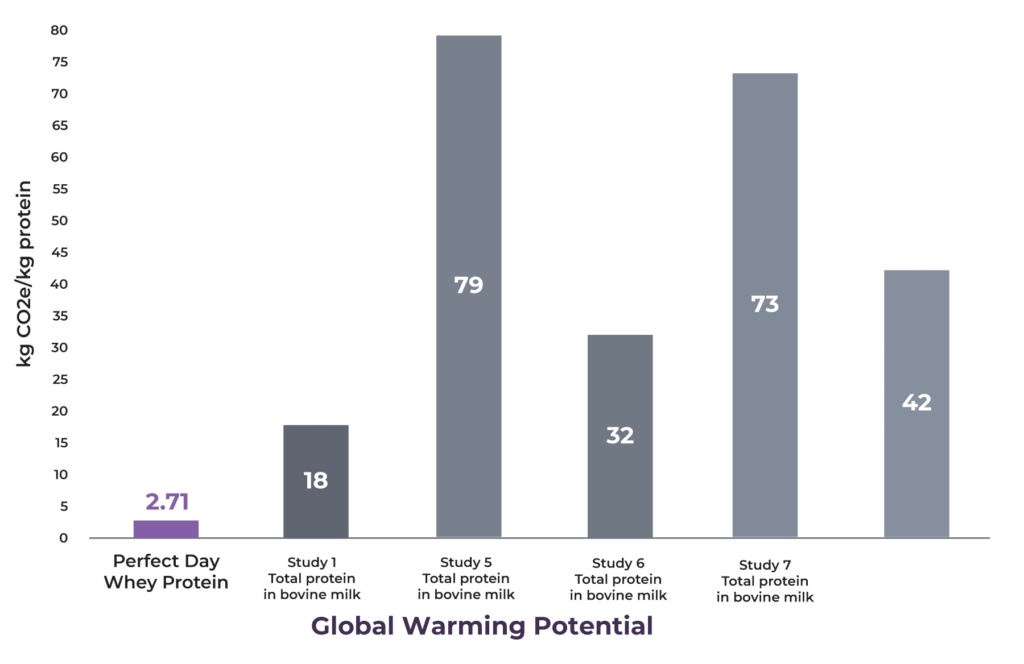

So how does the data stack up for alt-dairy? That’s what certain companies and scientists have tried to measure. Perfect Day – the Californian precision fermentation dairy pioneer – is one of them, conducting a life cycle assessment (LCA) of its whey in 2021 to measure its ecological impact. The goal was to find out the greenhouse gas emissions, energy demand and water consumption of precision-fermented dairy, and how that compares with traditional bovine milk.

Perfect Day’s ISO standard-reviewed LCA found that the company’s animal-free whey has 91-97% lower greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, 29-60% lower energy demands, and 96-99% of water consumption than conventional whey protein. To put this into context, if all Americans switched to its whey, it would save up to 246 million tons of CO2e in emissions – that’s equal to 28 million households’ annual energy use (all New York and Californian homes combined), or up to 53 million passenger vehicles driven for a year (all the cars in New York, California, Texas and Florida combined).

Additionally, it would save the amount of water needed by 187 billion people for daily indoor home use. If the US continues its current consumption rate of traditional dairy, it would require 32% of the total lighting energy consumed by the country’s residential and commercial sectors.

As for its own GHG emissions, the biggest factor is the utilities, accounting for 40% of Perfect Day’s total emissions. The company says utilities are the largest contributor to GHG emissions, owing to the composition of the US electric grid, which primarily comprises coal (31%) and natural gas (33%).

Developing its fermented whey makes up 25% of the emissions, many due to the production of glucose via starch hydrolysis (which is responsible for 83% of these protein development emissions). Utilities and glucose production are also the primary causes of energy and water use, respectively.

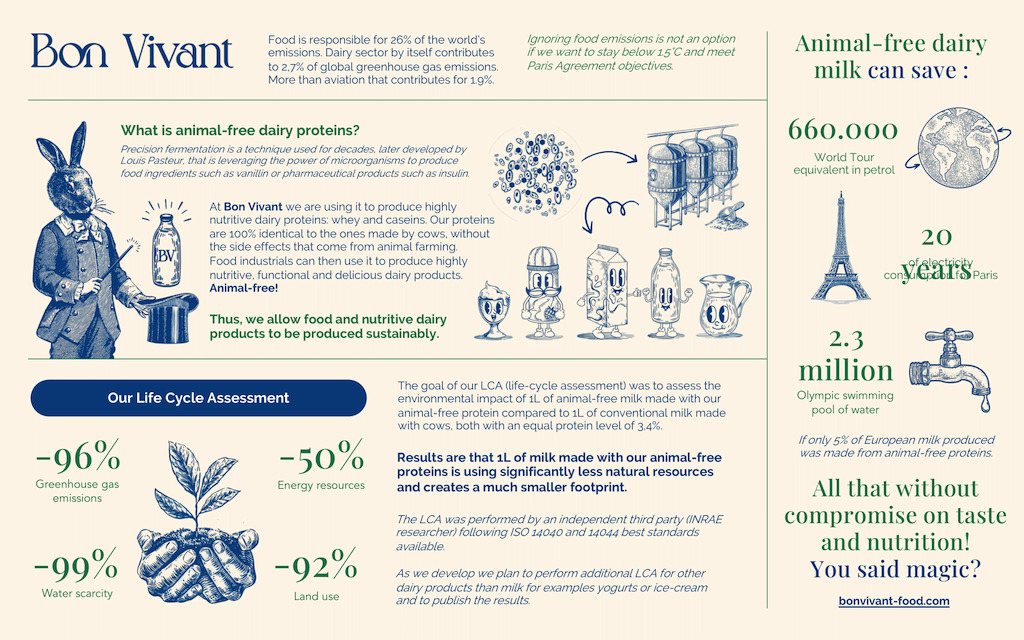

Across the Atlantic, French precision fermentation dairy producer Bon Vivant recently conducted its own LCA in 2022 for its whey alternative, which it says is the first of its kind in Europe. Similar to Perfect Day, the research was independently conducted according to ISO standards. The document, seen by Green Queen, showed similar results across multiple metrics – compared to conventional milk, it emits 96% less carbon and uses 99% less water 92% less land. In terms of energy use, Bon Vivant’s precision-fermented dairy requires only half as much power as traditional dairy production.

The company says that if only 5% of European milk was animal-free, it would save the equivalent of 660,000 tours of the world in petrol, 20 years of electricity consumption in Paris, and 2.3 million Olympic swimming pools of water (note: we have not verified these numbers).

De Novo Foodlabs: impact assessment of its fermentation-derived lactoferrin

Meanwhile, British-South African company De Novo Foodlabs, which makes lactoferrin – a component of the whey protein in milk – from precision fermentation, also published an environmental impact report comparing its NanoFerrin to the conventional dairy version.

The LCA was conducted by marketing intelligence and impact analytics firm Boundless Impact Research & Analytics based on projected manufacturing and performance data De Novo provided from its manufacturing operations in Cape Town, South Africa.

Boundless found that De Novo’s animal-free protein would have a GHG footprint of 169kg of CO2e, which is over 99.9% lower than conventional lactoferrin. Fermentation-derived biogenic CO2 emissions are responsible for 34.6% of its total GHG footprint, while production of sugar alcohol accounts for 13.5%.

The latter is also responsible for 87.5% of NanoFerrin’s land use footprint of 16.3 sq m years per kg of protein – also over 99.9% less than traditional lactoferrin. This figure carries over to water use as well, with De Novo Foodlabs stating it uses 75.8 litres of water per kg of its precision-fermented dairy protein.

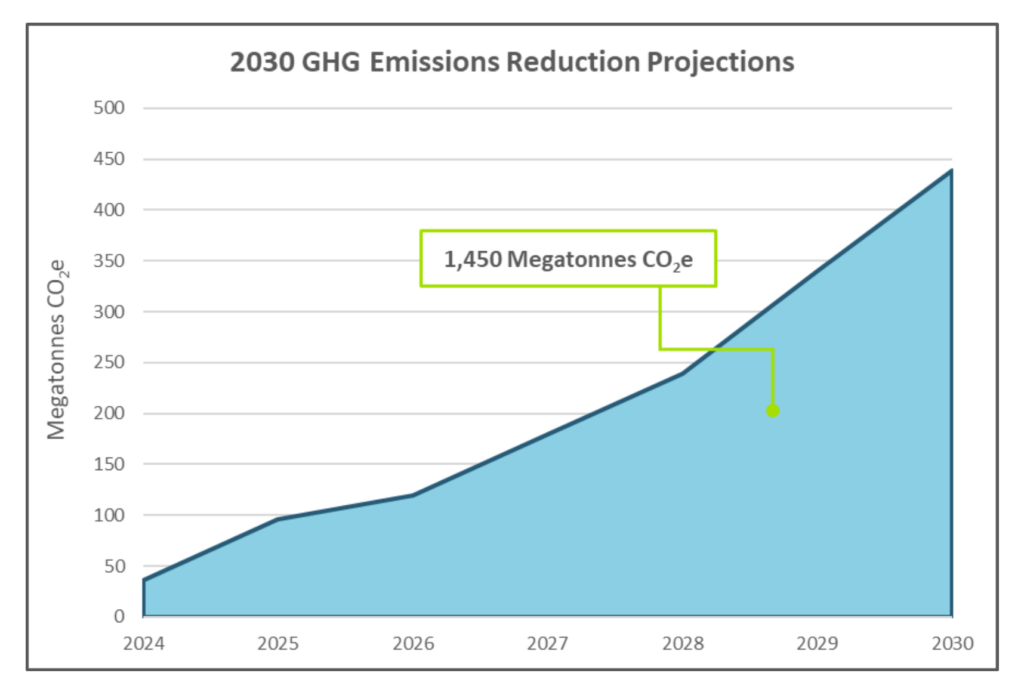

The company claims that replacing animal-derived lactoferrin with its NanoFerrin could reduce emissions by 1,450 megatonnes of CO2e from 2024-30 – equivalent to removing 46 million gasoline-powered cars from roads in that period.

Independent scientific research LCA results

However, non-company research carried out by scientists last year found that the environmental impact and water scarcity footprint of precision-fermented dairy are in the same range as dairy, with the main contributors being sugar and electricity production. The carbon footprints can be improved for both groups if renewable energy and food industry sidestreams are used.

Researchers noted that “the footprints of proteins and other food ingredients produced by cellular agriculture and traditional agriculture are not static – instead, there is potential for a significant reduction”. As knowledge and tech related to precision fermentation evolves – and combines with renewable energy – its footprint could enhance “remarkably”.

It’s worth noting that the researchers said that a full LCA would provide a better picture, as they only assessed two metrics: emissions and water use.

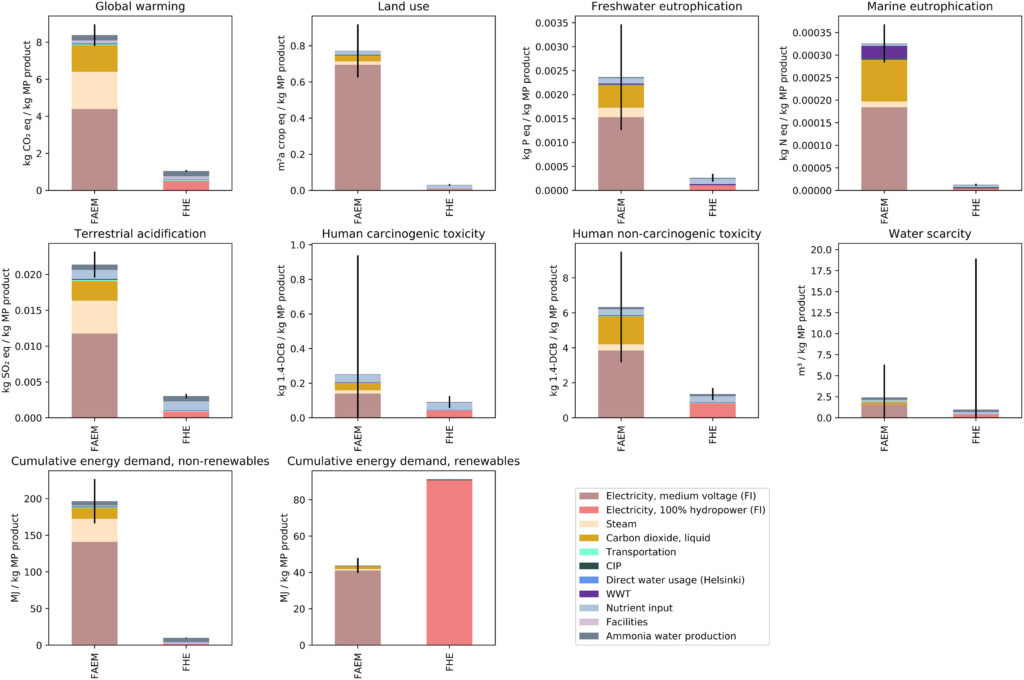

Along these lines, an independent LCA focused on the different forms of energy used to produce all kinds of animal-free proteins from precision fermentation. Published in the journal ScienceDirect in 2021, it concluded that precision-fermented proteins had a 53-100% lower environmental impact than animal-based proteins.

It compared the production of microbial protein from regular energy sources and hydropower and found that using the latter led to a significantly better performance across all metrics. Land use was 25 times less, and global warming potential was eight times less per kg of protein. Using hydropower also had a substantially lower impact on eutrophication, acidification and human toxicity. These results echoed another precision-fermentation-focused LCA published a year earlier.

The ScienceDirect study stated that further research is needed to understand the wider climate impacts of replacing animal protein with precision-fermented alternatives, including changes in land use, energy generation and diets. “Ultimately, the environmental benefits gained through microbial protein will be determined by how much and what type of products consumers choose to replace with microbial protein,” the researchers concluded.

The differing results across the multiple LCAs could be attributed to a number of factors, including feed materials (whether it’s glucose or sucrose), energy sources and the use of renewable power, and the different ways to calculate water scarcity footprints, which can vary across regions and assessments.

What do consumers think?

As of now, there are only a handful of consumer-facing precision fermentation brands, amongst them Modern Kitchen cream cheese, Brave Robot ice cream and Bored Cow milk – and most of these are exclusively available in the US. The average grocery shopper remains unaware of this technology, with researchers starting to canvas attitudes towards it and early results suggesting consumers are open to it.

In February 2022, the results of a joint study by German precision fermentation company Formo and the University of Bath found encouraging signs. The report highlighted a significant level of consumer enthusiasm and a strong curiosity about animal-free dairy amongst the 50 or so participants surveyed, including people from Germany, the UK, Singapore, and the US.

In March of this year, a white paper titled ‘Fermenting the Future: The Expanding Potential of Precision Fermentation in Product Manufacturing’ was published by the Hartman Group, Perfect Day and Cargill, delving into consumer sentiments regarding food technology, particularly focusing on precision fermentation. The research involved surveying over 2,500 adults in the US, and 77% of those who were familiar with precision fermentation expressed their likelihood to buy products derived from this tech.

One part of the puzzle is still up for debate: what should dairy products made via precision fermentation be called? A couple of years ago, it seemed animal-free dairy was the early industry consensus and Formo’s aforementioned report confirmed this was the preferred choice for the consumers surveyed, though other names like cell-cultured dairy, lab-grown dairy or microbial dairy are sometimes used by mainstream media. More recently, companies in the space have been exploring ‘whey protein from fermentation’, with Perfect Day CMO Allison Fowler telling AFN: “We’re seeing that for some consumers, ‘animal-free’ can sometimes be conflated with plant-based.”

Jason Rosenberg, head of business development at Israeli precision fermentation dairy company Remilk, told Green Queen in April that nomenclature is still very much a work in progress, and says that further research is needed. “It’s not possible to have true consensus over complex topics like nomenclature without additional research and study. We all need to know more about this. Until we know more, it’s difficult to jump to a conclusion.”

What’s clear is that the industry needs to come together to ensure the best possible name is used to introduce this technology to mainstream consumers as more products enter the retail market The US-based Precision Fermentation Alliance (PFA) and Food Fermentation Europe (FFE) are a start. Both industry-led organizations have recently been formed to address such matters. As per PFA’s launch announcement, the alliance aims to “establish global transparency around ingredients and foods made with precision fermentation to build trust and familiarity among consumers…[and] educating and engaging key stakeholders throughout the food industry value chain, to establish best practices regarding regulatory, manufacturing, food safety, and communications standards and compliance”.

So, what’s the verdict? Precision fermentation dairy vs. conventional dairy

All the LCAs reviewed have consistent results, though with some variance: producing dairy proteins using precision fermentation is lower in GHG emissions than conventional dairy, particularly if the energy sources used were renewable. Meanwhile, dairy’s externalised costs go beyond GHG emissions: these include heavy antibiotic use in animals (which increases human superbug resistance risk), excess growth hormone use (which has been linked by researchers to a rise in certain cancers), land footprint, and animal cruelty (dairy cows are forcibly impregnated so they can keep on producing milk).

Water usage is a serious problem for the industry too. California is currently facing droughts and water shortages (and the US is running out of groundwater), with the state’s large dairy industry partially responsible. The latter accounts for more than its fair share of methane emissions too.

Precision fermentation dairy is undoubtedly an alternative to all of these issues. Given our growing global appetite for dairy products, especially in highly populated countries like China, and given that livestock animal agriculture accounts for between 11% and 19% of all GHG emissions, it seems reasonable to continue investing in this alternative way to produce dairy proteins.

With additional reporting and research by Sonalie Figueiras.

This article was updated on September 21, 2023 to include newly released impact assessment data by De Novo Foodlabs about its fermentation-derived lactoferrin.