Deep Dive: How the Livestock Lobby Sunk Its Teeth Into the EU’s Animal Welfare Legislations

10 Mins Read

Food and climate journalist Thin Lei Win shares more details and context about the Lighthouse Reports investigation she worked on with multiple journalists and co-published by The Guardian and IRPI exploring how meat lobby groups pushed back on the EU’s proposed ban on caged farming, which is now on hold.

Over two crisp Spring days in early May, nearly 320 carefully vetted attendees gathered at the Renaissance Arlington Capital View Hotel in Arlington, Virginia, for an annual summit organised by the Animal Agriculture Alliance, a non-profit with very close ties to the American meat and dairy industry.

One of the speakers for a session titled “Responding to Animal Rights Extremism” was Andrea Bertaglio, campaign manager for European Livestock Voice, a coalition of 14 livestock industry associations.

ELV’s founding partners include Copa-Cogeca, Europe’s most powerful farm lobby whom we exposed a few months ago as representing mainly the interests of the industry and not small-scale farmers, as well as the fur, leather, foie gras, feed, and poultry producers. They mainly represent the large-scale, industrial livestock sector.

ELV was set up in 2019 “to bring back a balanced debate around a sector that is playing such an essential role in Europe’s rich heritage and future”. It has used the slogan “Meat The Facts” to downplay livestock’s role in climate change and portray animal rights activists and environmentalists as out-of-touch urbanites who want to end animal agriculture in Europe.

In his presentation at the AAA, which Lighthouse Reports obtained, Bertaglio said he has been an environmental journalist for 18 years. “And that’s still my official identity. But my real job now is to work to inform the public about livestock production, actually,” he said.

He also said: “This year in particular, we are all focused in Brussels, at least on the revision of the animal welfare legislation.” He ended his speech with a future strategy. “I’d like to go to the scientists. The ones publishing papers against meat, against livestock and say, “Why are you saying that? Data? Fact?” So that’s the next step.”

In a Q&A after the presentation, he expanded on what he thought was going wrong in Europe.

“A big problem is that we humanise, anthropomorphise… (animals),” he said.

“We need to tell people that an animal is not a person. So when you think that you leave a cow grazing and it’s necessarily better because you have this bucolic image of livestock. For the cow, it’s not necessarily good because she is exposed to predators, to diseases, weather conditions.”

He also added in an online Q&A – “The public perception of the so-called “intensive farming” is always negative. What we are doing is to inform (on social media, too) about the advantages of raising animals in “confined” places: they are better fed, protected, treated, cured, etc. Or we often communicate the fact that “factory farming” is more efficient when it comes to water, natural resources use or that a stable can be a barrier to the diffusion of viruses and to pandemics.”

Bringing US-style tactics?

Also at the AAA was Jack Hubbard, an owner and partner of notorious U.S. PR firm Berman & Co, who showed clips of attack ads his company had produced and described how they aim to shift the discussion away from issues of animal welfare, the environment, or workers rights and onto critiques of animal advocacy groups themselves.

The PR firm has a history of attacking animal rights groups, scientists, journalists, and alternative proteins.

In response to Hubbard’s presentation, Bertaglio said, “We are going to do something similar possibly in Europe, like your videos. So I’d get in touch with you for sure.”

In a wide-ranging interview a few days ago with The Guardian and EU Scream, Lighthouse Reports’ media partners in this investigation, Bertaglio did not deny expressing a desire to bring U.S.-style stock tactics to Europe but suggested it was more of a joke and that he has neither done it nor proposed it to ELV.

He also denied being a lobbyist and said he is “in transition” from writing for newspapers to communication work.

“But still, my job is more (like) journalists because what I’m doing with European Livestock Voice is informing, writing articles in a balanced way, interviewing people, experts,” he said. It also includes clearing up misunderstandings arising from Western Europeans’ tendency to “humanise animals a bit too much”, he added.

“I’m trying to see and to consider both sides of the story,” and “nobody is denying” livestock is a problem when it comes to emissions, he said.

“But there is also a lot of science saying that livestock can be helping and agriculture can help in the carbon sequestration. But this message you barely see. Let’s face it… when (do) you read an article about a scientific report showing that livestock can contribute in carbon sequestration? Never.”

Bertaglio also cited Frank Mitloehner, the head of an agricultural research centre at the University of California, as well as the signatories of the Dublin Declaration, as experts whose unbiased views he seeks.

Mitloehner’s academic group “receives almost all its funding from industry donations and coordinates with a major livestock lobby group on messaging campaigns”, reported The New York Times in 2022. Meanwhile, many signatories of the Declaration have ties to the meat industry, according to newly published articles by The Guardian and Unearthed.

Rhetoric vs Reality

One other thing Bertaglio said at the AAA was that ELV’s target is the Brussels bubble because EU legislation is mostly against livestock.

This is a curious statement to make because a recent study from Stanford University that looked at support for livestock versus novel technologies in the EU and the U.S. found that a vast majority of research & innovation, government policies, and subsidies go towards animal farming.

In fact, in the EU, the sector already gets a lion’s share – about 50% – of the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP), a system of subsidies that accounts for a third of the bloc’s budget, according to the study.

While the money given in Europe is not tied explicitly to a commodity, the researchers calculated their findings by using the farm accountancy data network (FADN) to see which farms are receiving the funds and if they are specialised in dairy or meat production.

“They are typically larger farms and have more hectares. The smaller producers don’t necessarily get enough (funds) because they don’t have enough land,” said Simona Vallone, lead author of the study and Earth System science research associate at the Stanford Doerr School of Sustainability.

In addition, farmers were not required to implement specific environmental conservation practices to reduce the impact of animal farming. If they didn’t comply with environmental requirements, they didn’t immediately lose access to subsidies, Simona told me, adding that legal decisions have also favoured animal farming.

“In Europe with the ruling of the European Court, it’s not possible anymore for oat milk or soy milk to be called milk,” she said. “So it’s challenging for a company to make decisions on investments when they’re unsure whether or how they’re going to market it. The name really tells a lot about how (the food) will be used. If we call it burger, if we call it milk, we know how we’re going to use (them) in a meal.”

All of this is a problem, because – as regular readers of Thin Ink know – agriculture is both a key contributor and a victim of climate change.

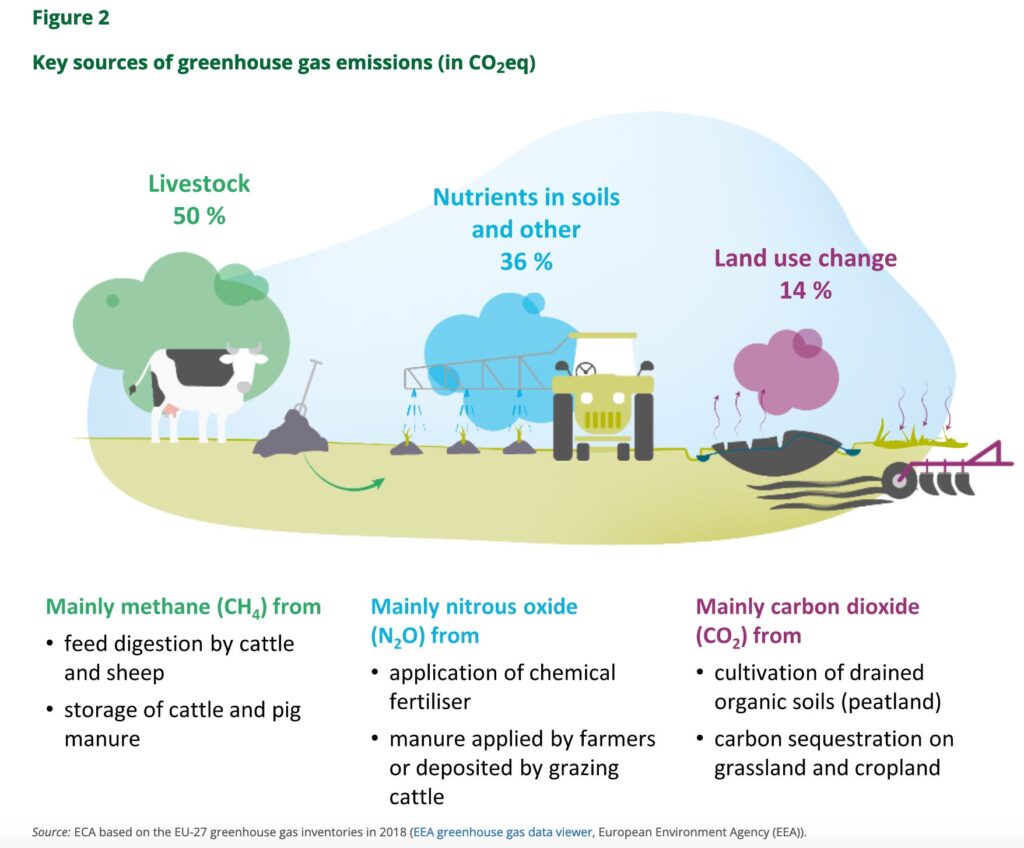

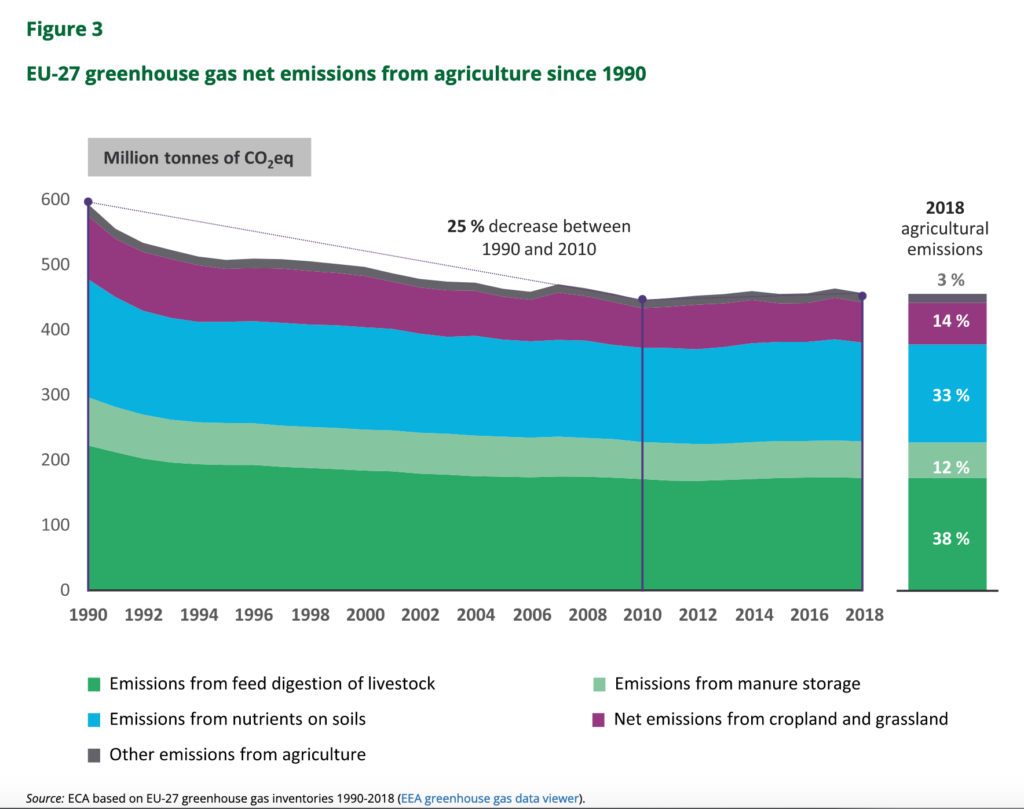

In Europe, agriculture is responsible for 94% of ammonia, a harmful air pollutant, and 54% of methane, the second most important greenhouse gas contributing to climate change, according to the European Environment Agency (EEA). Livestock is the main source for both gases and their emissions in Europe have barely fallen over the past two decades, the EEA said.

A 2021 report from the European Court of Auditors also raised concerns about the CAP budget not mitigating climate change.

“Livestock emissions, mainly driven by cattle, represent around half of emissions from agriculture and have been stable since 2010. However, the CAP does not seek to limit livestock numbers; nor does it provide incentives to reduce them. The CAP market measures include promotion of animal products, the consumption of which has not decreased since 2014,” it said.

Doubting science

Unfortunately, our reporting discovered that DG AGRI, the department of the European Commission responsible for agricultural policy, seems to disregard such scientific data.

A leaked internal DG AGRI document we obtained showed the head of the department pushing back on reasonable and scientifically proven criticism about livestock.

The authors had written: “Similarly, while the CAP Plans can contribute to climate change mitigation, in particular by enhancing carbon sequestration, efforts on livestock emissions are limited and climate adaptation requires a more holistic, longer-term approach”.

The head of DG AGRI left a typed comment:- “This point needs to be worked on and be more sophisticated. No general livestock bashing”.

Two former officers at the department told us about their disappointment and anger at the general disinterest, starting from the highest echelons of the department, in sustainability and environmental issues around agriculture.

“The default position is defence: resist, resist, resist, instead of acknowledging problems, engaging with science and working with other relevant (directorate-generals) to devise credible solutions. This is what a public administration should be doing, and they are failing,” one told me.

“AGRI is failing to recognise what its role should actually be – ensuring genuinely sustainable agriculture, not protecting the incumbent actors and the status quo. So they are a danger to the agriculture sector, which they purport to be responsible for.”

A second officer recalled that staff who ask questions about sustainability, especially on the impact of animal farming, risk losing credibility in the eyes of the department higher-ups. “I think my work in AGRI was very disheartening and a bit of disillusionment. It was different from the way I wanted to contribute.”

The Commission did not respond to emails with detailed questions.

How the animal welfare laws became undone

Let’s now go back to something Bertaglio mentioned three times at the AAA – ELV’s focus on the revision of animal welfare legislation in the EU – because we discovered that the alliance’s partner associations have been very very active in pushing to either water down or abandon some of the laws.

Back in October 2020, the EU — so often criticised for its lack of democracy — received a truly democratic request. 1.4 million citizens from all over Europe asked the EU to end the practice of keeping farm animals in cages and increase their welfare standards. In June 2021, it was adopted by the EU parliament with an overwhelming majority and the European Commission decided to revise the current legislation in line with the citizens’ wishes.

The set of four laws was supposed to end practices such as keeping farm animals in cages, slaughtering day-old chicks, and the sale and production of fur.

Three years later, those promises are in tatters. All but one have been dropped, including the ban on caged farming, from the European Commission’s 2024 work programme and it is anyone’s guess when or if they will appear in the future.

This is despite the overwhelming support for these laws. A survey released this month – and conducted at the height of inflation – found that 84% of Europeans want more protection for animal welfare and 60% are even happy to pay more for it.

Interviews with EU officials familiar with the file recounted aggressive lobbying against the laws by groups such as the European Livestock Voice (ELV) and its partner associations.

Documents we received through a freedom of information request also showed that in at least six meetings between Sep 2021 and Feb 2023, ELV partner associations pushed DG SANTE, the branch of the commission tasked with drafting the animal welfare laws, to reconsider ending caged farming. One asked “the Commission to resist the pressure from NGOs”, saying, “NGO perspectives do not reflect the views of the broad public/ the society.”

EFSA, the European Food Safety Authority, came under particular criticism from Copa-Cogeca and ELV, according to sources. Between August 2022 and May 2023, EFSA published a total of 11 scientific opinions relating to animal welfare that included recommending more space, lower temperatures, and shorter journeys to improve animal welfare during transport and against mutilation, feed restriction and the use of cages for broiler chickens and laying hens.

On the exact same day, EFSA released its opinion on broilers, Copa-Cogeca, EFFAB, and AVEC Poultry – all founding partner associations of ELV – criticised EFSA’s opinion on broilers as “the roadmap to unsustainable poultry production in Europe”.

We sent two e-mails to ELV asking for comment and they responded with a few short paragraphs. They told us that each partner association provides between €1,000 and €5,000 annually to fund its activities. However, ELV did not address our questions around their lobbying tactics and Bertaglio’s comments at the AAA.

We followed up with more specific questions, including their annual budget. Their response: “We believe we have already provided sufficient responses to your enquiry, but would like to clarify as stated previously that European Livestock Voice is a communications platform and as an entity does not engage on a policy level.”

However, we know ELV requested a meeting with Frans Timmermans, the then-executive vice president of the Commission in April 2021. The minutes of that meeting in May 2021 are here.

Look, lobbying by both sides has been around for as long as politics has been. What is worrying in this particular instance is the extent to which the will of the many could be thwarted by the demands of the few and the strategies used, particularly the attacking and questioning of science, similar to the tactics of the tobacco and fossil fuel companies.

This is an edited and web-adapted version of the 30th October 2023 edition of the Thin Ink newsletter, a weekly publication on food, climate, and where they meet by journalist Thin Lei Win – subscribe here.