Only 1% of Climate Reporting in Czech Media Tackles Animal Agriculture: Study

5 Mins Read

Czech media outlets are vastly underreporting the link between food and climate change, despite the sector contributing to 7.6% of the country’s emissions.

The food system is responsible for a third of global greenhouse gas emissions, but this is hardly discussed in the media’s coverage of climate change. One analysis, for example, found that 93% of press articles about the climate crisis don’t mention animal agriculture, even though that industry is responsible for up to 20% of all emissions.

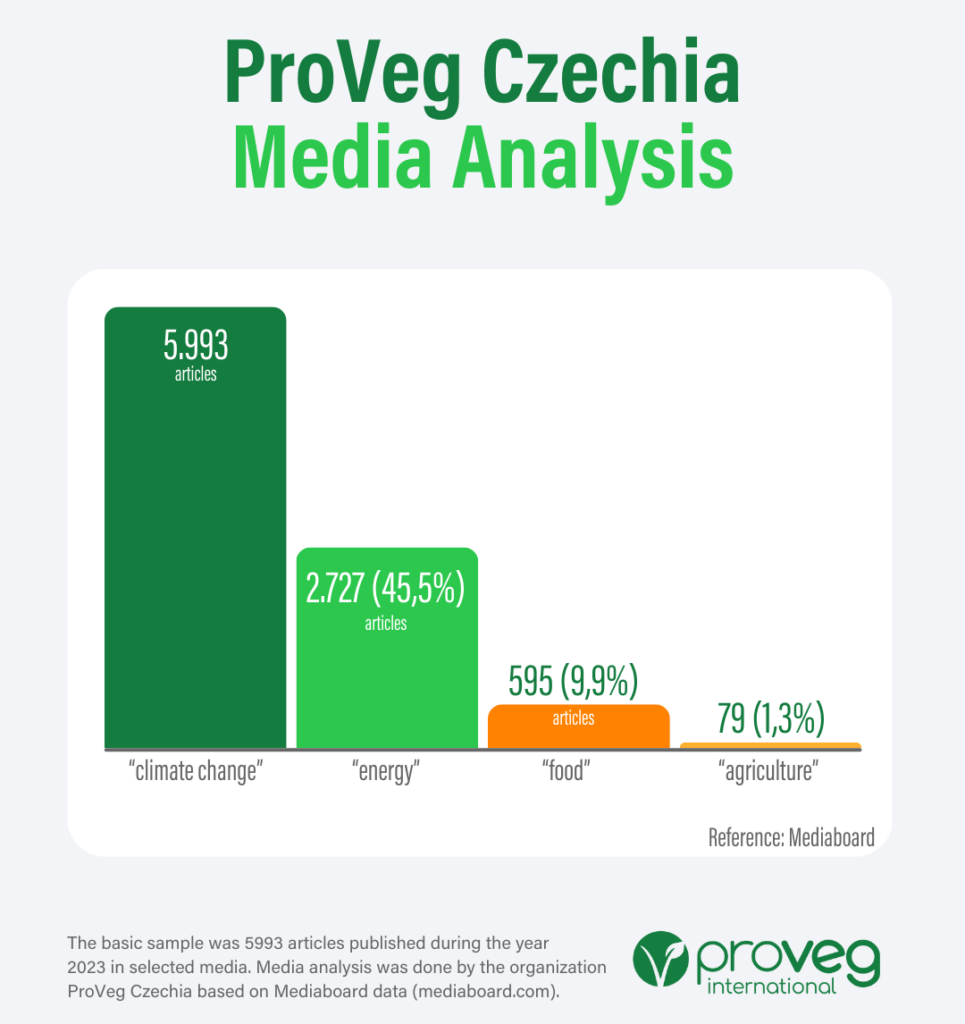

Now, a similar – albeit more specific – analysis of Czech media has found a significant disparity in the coverage of environmental issues. Conducted by non-profit ProVeg Czechia, which based the assessment on data from media insights platform Mediaboard, the research shows that media outlets in the country vastly overlook the climate impact of food and agriculture, especially when compared to the energy sector.

Of the 5,993 articles assessed, only 595 (10%) mentioned food, while 2,727 (45.5%) discussed the energy sector. Things are even worse when you look at agriculture – particularly meat and dairy – which accounted for just 1.3% of all climate coverage in Czech media. But a drastic shift in messaging and awareness is needed, considering that Czechia is the seventh-largest EU country in terms of per capita meat consumption.

Animal-based foods are twice as polluting as plant-based foods, with meat alone responsible for 60% of the food system’s emissions globally. Ignoring this impact is detrimental to country’s climate plans and the global fight to limit warming to 1.5°C by the end of the century – but the results of this study are also all too familiar.

“It is vital to acknowledge that we have never consumed more meat than we do now. This overconsumption is taking its toll on both human health and that of the planet,” said Eva Hemmerová, communications manager for ProVeg Czechia. “The media needs to investigate and report on the profound impact that our dietary choices have on the environment.”

Climate-food gap exacerbated by ‘feedback loop’

ProVeg chose stories from 23 print and online outlets, based on keywords related to climate change, agriculture, meat, dairy, energy and food. But what made the non-profit explore the underreporting of food and agriculture? “We had this assumption when looking at the Czech media coverage, and it made us think that it would be interesting to have some data to back our opinion, which turned out to be quite accurate,” Martin Ranninger, co-director of ProVeg Czechia, told Green Queen.

“We noticed that agriculture wasn’t covered as much as energy and other environmental issues. This concern grew from our regular monitoring and past observations of media trends,” he added.

According to one estimate, agriculture makes up 7.6% of all emissions within Czechia. Nearly half of this share (49%) comes in the form of methane from livestock farming. And this is before you account for total consumption emissions in the nation.

So why does the gap exist in the press? Ranninger ascribes it to a “feedback loop”. “People (including journalists) know little about the connection between food and its impact on the climate crisis, so the media cover this topic less, and people know little about it.”

Reducing the number of livestock and the consumption of meat and dairy would help bring down these emissions considerably. And it seems there is some awareness about this link – a separate survey from last year reveals that 40% of Czechs would be in favour of limiting or capping the amount of meat and dairy people can buy, and 67% woud support carbon labelling for all food products.

ProVeg Czechia is calling on local media outlets to adopt a more balanced and comprehensive approach to reporting on climate issues. This stands to serve not just Czechia’s own climate goals – as of 2022, its per capita GHG emissions were three tonnes higher than the EU average – but the EU’s targets too.

Research has found that 82% of its common agriculture policy budget goes towards livestock farming (four times more than what it spends on plant-based foods). But animal agriculture makes up 84% of the EU’s food emissions, despite only supplying 35% of calories and 65% of proteins consumed in the region.

Czechia’s position on alternative proteins

Next month, EU citizens will vote in the latest European Parliament elections, and since 2024 has been described as a year of climate elections, environmental issues should be high on the agenda. But the EU has been infamous for its complex novel foods regulatory framework, which has prevented up-and-coming cultivated meat startups from launching in their home regions and look elsewhere, and kept out products from leading international players like Impossible Foods (whose precision-fermented heme ingredient in its flagship burger is not approved for sale in the region).

In fact, countries have been looking to further restrict these foods from being commercialised in the EU. Italy has already banned cultivated meat, while France and Romania are hoping to do the same. In fact, a coalition of EU member states – including Czechia – presented a case for further regulations against cultivated meat in an Agrifish Council meeting in January.

“The European Commission must work hard to allay concerns expressed by EU agriculture ministers about cultivated meat to prevent the EU from missing out on the huge economic and environmental benefits of the new food technology,” said Ranninger. “We already have a robust regulatory procedure in place that will ensure that all cultivated foods that will appear on the EU market are safe, so we do not need to reinvent the wheel.”

He added that the EU Commission needs to reassure concerned member states that its “world-class regulations mean cultivated meat will be a win-win” for the bloc. For its part, the Czech government has invested in these proteins, awarding €200,000 in grants to local cultivated pork startup Mewery. Fellow Czech producer Bene Meat will soon introduce cultivated pet food too.

“We appreciate the efforts to open the discussion and hold informational seminars in the Chamber of Deputies and Czech ministries, in which ProVeg has the opportunity to participate. However, it is necessary to note the absence of specific steps and policies supporting the plant-based sector,” Ranninger said when asked about Czechia’s alternative protein policies.

“There is a need for fair subsidy systems and stopping restrictions on plant-based denominations promoted by the dairy and meat lobbies, which threaten the EU single market and paradoxically may confuse consumers.”